Michigan Health Care Regulators Just Restricted Access to Promising New Cancer Treatments

The state's largest hospital chain didn't want the competition.

A state commission, acting at the behest of Michigan's largest hospital chain, voted on Thursday to restrict cancer patients' access to promising, potentially lifesaving treatments.

It's another example of the problems caused by little-known state-level health care regulations known as Certificate of Necessity (or, in some states, Certificate of Public Need) laws. These laws are supposed to slow down increasing costs, but they often end up being used to restrict competition, often at the request of powerful hospital chains.

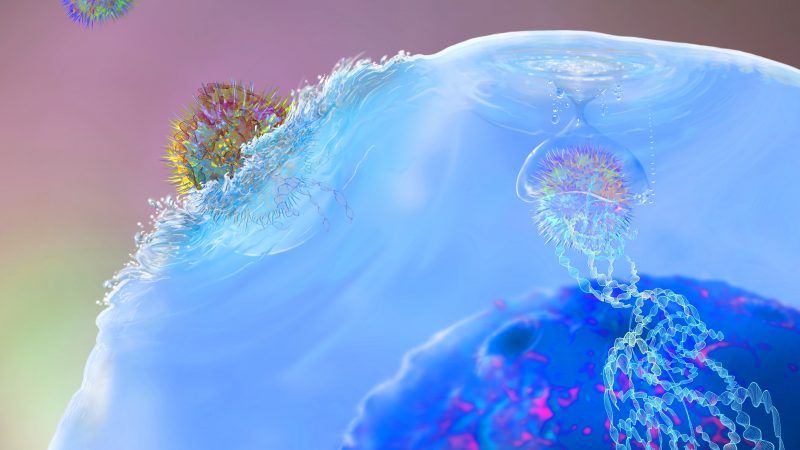

That's exactly what seems to have happened in Michigan, where the state's Certificate of Need Commission voted Thursday to impose new accreditation requirements for health care providers who want to offer new immunotherapy cancer treatments. Those treatments attempt to program the body's own immune system to attack and kill cancer cells, and they have become an increasingly attractive way to combat cancer alongside more traditional methods, such as surgery, chemotherapy, and radiation.

One particularly promising type of immunotherapy involves literally bio-engineering T-cells—the foot-soldiers of the body's immune system—and equipping them with new Chimeric Antigen Receptors that target cancer cells. This so-called "CAR T-cell therapy" is every bit as badass as it sounds:

But under the new rules adopted by the Michigan Certificate of Need Commission, hospitals will need to go through unnecessary third-party accreditation processes before being able to offer CAR T-cell therapies. Even after obtaining that additional accreditation, hospitals would have to come back to the CON commission for another approval—a process that effectively means only large, wealthy, hospital-based cancer centers will be able to offer the treatments.

The new rules were "opposed by cancer research organizations, patient advocates and pharmaceutical companies, who argue it would add an unnecessary level of regulation and deny many patients access to potentially life-saving treatment," reports Michigan Capital Confidential, a nonprofit journalism outfit covering Michigan politics.

In favor of the new rules? The University of Michigan Health System, the state's largest hospital system, which argues that the new rules are necessary for patient safety.

To be clear: It's not a question of patient safety. In 2017, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved two CAR T-cell therapies for children suffering from leukemia and for adults with advanced lymphoma. Although the technology is still being developed and other uses of T-cell therapies are yet to be approved by the FDA, the Michigan CON Commission does not do medical testing. Like similar agencies in other states, the extent of its mandate is purely economic, not medical.

Anna Parsons, a policy coordinator with the American Legislative Exchange Council, points out that the safe administration of CAR T-cell therapy does not require hospitals to make new capital investments—which is the only time CON laws should apply. Literally any FDA-certified hospital should be capable of offering these treatments, since all the high-tech bioengineering is done at other locations. The only thing that happens at the hospital is a simple blood transfusion.

Though the specific applications of CON laws differ from state to state, their stated purpose is to prevent overinvestment and keep hospitals from having to charge higher prices to make up for unnecessary outlays of capital costs. But in practice, they mean hospitals must get a state agency's permission before offering new services or installing new medical technology. Depending on the state, everything from the number of hospital beds to the installation of a new MRI machine could be subject to CON review.

As part of that review process, it's not uncommon for large hospital chains to wield CON laws in order to limit competition, even at the expense of patient outcomes.

From 2010 to 2013, for example, the state agency in charge of Virginia's CON laws repeatedly blocked attempts by a small hospital in Salem, Virginia, to build a neonatal intensive care unit (NICU), in large part because a nearby hospital—which happened to have the only NICU in southwestern Virginia—objected to the new competition. Even after a premature infant died at the Salem hospital, state regulators continued to side with the Salem hospital's chief competitor, against the wishes of doctors, hospital administrators, public officials, and patients who repeatedly testified in favor of letting the new NICU be built.

Even when the outcomes aren't as tragic as dead babies or untreated cancer patients, CON laws have adverse consequences. In 2016, reseachers at the Mercatus Center at George Mason University found that hospitals in states with CON laws have higher mortality rates than hospitals in non-CON states. The average 30-day mortality rate for patients with pneumonia, heart failure, and heart attacks in states with CON laws is between 2.5 percent and 5 percent higher even after demographic factors are taken out of the equation.

When it comes to CAR T-cell therapy, there does not seem to be any compelling reason for Michigan regulators to use CON laws except to explicitly limit which hospitals can provide those treatments.

"We will never know how many more lives this therapy could have saved if the added time and expense these onerous regulations put in place discourage hospitals and clinics from providing treatment in the first place," Parsons wrote this week in The Detroit News.

Under Michigan law, the legislature has 45 days to review and overturn the decisions of the CON Commission. Here is one situation where that is exactly what it should do.

Editor's Note: As of February 29, 2024, commenting privileges on reason.com posts are limited to Reason Plus subscribers. Past commenters are grandfathered in for a temporary period. Subscribe here to preserve your ability to comment. Your Reason Plus subscription also gives you an ad-free version of reason.com, along with full access to the digital edition and archives of Reason magazine. We request that comments be civil and on-topic. We do not moderate or assume any responsibility for comments, which are owned by the readers who post them. Comments do not represent the views of reason.com or Reason Foundation. We reserve the right to delete any comment and ban commenters for any reason at any time. Comments may only be edited within 5 minutes of posting. Report abuses.

Please to post comments

""A state commission, acting at the behest of Michigan's largest hospital chain, voted on Thursday to restrict cancer patients' access to promising, potentially lifesaving treatments."'

Would not the new Right to Try law Trump signed trump this?

Don't think so. That was for FDA to approve use before final trials were done iirc.

Generally, no. The Right to Try law allows you to get into clinical trials that you might otherwise be locked out of. The treatments being discussed above are past the clinical trials stage - they are established treatments with completed FDA approvals.

In other words, the Right to Try law doesn't apply because Congress didn't think anyone would be stupid enough to restrict medical procedures on the basis of economic protectionism. (Or more generously, that Congress does recognize that some states are that stupid but also knows that it's not the feds' job to fix every stupid thing that states do.)

"[B]ecause Congress didn’t think anyone would be stupid enough to restrict medical procedures on the basis of economic protectionism."

I don't think "stupid" is the word that should be used here. They know exactly what they are doing and the effect thereof.

It may be that they are also doing clinical trials. A lot of those are still going on and are very common in oncology. Don’t think it matters much either way in this case.

Really in cancer treatment every patient is a clinical trial in a sense because tumors are not alike. A leukemia may respond one way in one patient and very differently in another.

just as Cindy explained I am inspired that some people can get paid $7036 in four weeks on the internet .

hop over to this site >> http://www.works55.com

I'm sure this sort of thing will never happen under "Medicare For All" (or whatever cutesy euphemism they end up using for socialist healthcare).

It would be Medicaid For All anyway. Surely they don't mean a program for everyone that pays 80% of the bill and leaves the rest up to the patient. They mean the patient pays nothing, like Medicaid.

The VA is an even better example than medicaid.

But "VA for all" probably didn't go over well in focus groups - - - - - -

I'm sure "Medicaid for all" didn't go over so well either.

Single Payer would also be the excuse they need to finally mandate certain lifestyle changes. If everyone else is paying for your healthcare, it will be easier for them for forbid you from smoking, vaping, fast food, salt, alcohol, contact sports, obesity, etc.

Don't forget gay sex.

I understand that the actual reason for (appropriately abbreviated) CON laws is to protect favored cronies. But how can anyone believe the nonsense that restricting supply makes costs lower?! WTF?!!!!!!

can anyone believe the nonsense that restricting supply makes costs lower?

simple, by restricting supply only those who need will buy thus the price will have to be lowered. laugh meter on

That's simple. Hospital A buys a $1M machine and needs 10 patients a day to recover their investment. They have 15 people a day who could use it, so there's a backlog.

Hospital B wants to buy the same machine. Problem: Now you have two hospitals who need 20 patients a day, but there are only 15. That means both hospitals will go bankrupt and there will be no hospitals.

Solution: Central planners tell hospital B to bugger off because hospital A got there first.

Real world reality: Hospital B is not stupid. They wouldn't buy the machine if they didn't think they could pay it off and stay afloat. Obviously they know something the central planners don't. Maybe they know there are more potential patients, but most are discouraged because of the backlog and waiting list at hospital A. Maybe they have staff with prior experience with the machine who know how to use it more efficiently, and hospital A staff is slow and inefficient.

And most important of all -- if hospital B is wrong, it's their money at stake.not the central planners'.

Really, really real real-world reality: There's no free market in health care, and expenditures are subsidized, directly and indirectly, in a way that makes the health care business a "cost-plus" proposition. (Not entirely; it's still possible for a facility to go broke, but they'll play chicken over that, hoping to be indirectly subsidized.) So the model is like that of public utilities: restricted competition in return for price controls, with the understanding that policy will be to allow even the stupidest of capital expenditures to be recouped. Therefore capital expenditures themselves have to be capped in some way.

So the idea is that if they let every hospital and clinic buy a(nother) MRI machine, everyone's insurance rates and government health care expenditures will go up to pay for those machines.

But given that a lot of the health care subsidy comes from the federal government, why, practically, would the state give a shit? When it comes to Medicaid, for what it's worth, the state could just not allow a facility to bill Medicaid. But what's the point in stopping private insurers from doing the same?

But it has been shown that it doesn’t change cost.

This hospital may be losing money on the new treatment but they do not care because they are building a top drawer oncology center and will have more of the routine patients.

Same for a new 3T MRI. They may lose something on it but the Ortho group will love it and they get all those knee and hip replacements.

So CON doesn’t work at all.

Depends on how you define cost. If you just look at price paid by the patient, probably not. But if you look at total expense associated with all use of the treatment - to include ineffective, inappropriate, and flat out harmful use (which could include failure to use a better alternative) then maybe not.

But that's also why it's really hard to speak about healthcare in market terms - in most other situations the assumptions are better defined.

A scalpel is really, really cheap. Used properly it can be incredibly beneficial at minimal risk. Used inappropriately it can inflict almost instant death. The thing is, we already have a really clear understanding of the reasons how and why. CAR-T is phenomenally complex, and we barely understand those same hows and whys.

Personally I think a great deal of caution is warranted, but I also think the CON process is an inelegant (to say the least) solution to the problem.

It is, but refractory leukemia is generally fatal, and CAR-T often works to treat it, so why not? So what if we don't understand it as much yet? Without it, the patient will almost surely die, and with it, the patient may survive.

Ultimately, though, I think the problem is too much thinking in terms of "we" with one-size-fits-all solutions dictated by bureaucrats and activists with zero skin in the game.

"Ultimately, though, I think the problem is too much thinking in terms of “we” with one-size-fits-all solutions dictated by bureaucrats and activists with zero skin in the game."

Oh no, it's people with skin in the game, just not usually the patients. Vested interests with deep pockets mostly. As with all things the ones with the least to lose tend to be the least risk averse.

"The thing is, we already have a really clear understanding of the reasons how and why. CAR-T is phenomenally complex, and we barely understand those same hows and whys."

Yes, but: "[T]he safe administration of CAR T-cell therapy does not require hospitals to make new capital investments—which is the only time CON laws should apply. Literally any FDA-certified hospital should be capable of offering these treatments, since all the high-tech bioengineering is done at other locations. The only thing that happens at the hospital is a simple blood transfusion."

I assume that's the same group that does things like make hospitals get on bended knee for permission for a new CAT of MRI, and fight the age old battles of "this here state ain't big enough for the 17 of us!"

Michigan's Certificate of Need statute is written in such a way that the commission's allowed to regulate any treatment, not just installation of equipment and facilities?! The only excuse I could see for such behavior is, "We need to confine the revenues from CAR-T treatment to these few hospitals so they can make back what they've already spent, or plan to spend, on the diagnostic and treatment capital for other things. You know, to make up for other hospitals not being allowed to buy those things. So we can hold overall costs in the state down while still allowing some people in the state to get these services somewhere." Otherwise it's just, "Fuck you, that's why!"

There is a cliche that says if aspirin were invented today the FDA would never approve it, or at least never approve it for OTC use. It's just too dangerous. And there is some truth there. Which tends to make anyone with a potentially promising treatment very cautious about it's early use.

The 'problem' with CAR-T is that, unlike a unique drug entity, it cannot be patent protected. Allowing the treatment process(es) to become something of a wild west.

Fine, if the creators or physicians who administer it want to be cautious, that may be wise. But keep the government out of that decision, especially when talking about terminally ill patients.

But then people will be able to do as they please and will take unnecessary risks. We can't have that in the land of the free and home of the brave.

Pretty much this. People who stand to benefit from carefully controlled use intended to minimize adverse events will tend to favor that same approach, and will strongly oppose those willing to entertain greater risk.

It is indeed a tragedy of the commons problem. In this case the 'resource' being depleted is continued use of (actually continued payment for) the treatment, and the manner of depletion is 'too many' poor outcomes.

Which brings us to the crux of the matter - the people who ultimately decide what "too many" is are largely insulated from the direct concerns of actual or potential patients.

THAT is where the solution to the problem lies. Until that aspect is addressed you will continue to see heavy restriction of treatment modalities in order to protect any potential golden egg laying geese.

The history of drug development is littered with drugs that did significant things in the body, but unfortunately in early testing displayed "too many" problems. And if you talk to enough researchers you inevitably hear the stories of the lost miracle cure and how "if they had only gotten it right" - be it patient selection, dose adjusting, etc. etc. etc. then "things would have been different."

Which is why--in particular for terminal illnesses--this entire philosophy makes no sense. While it's true that you certainly don't want something that causes instant death or great suffering, it's not like the "long term consequences" of metastatic cancer* are going to be anything better than the long term consequences of some treatment that might put it in remission.

*as always, with the exceptions of those cancers that are currently curable when metastatic, but then in those cases there is no need to experiment and the patient is not terminally ill.

The fact that you're going to die eventually isn't unusual. Everybody has a terminal illness called life. With the best treatment, you're mortal, and with the worst, you're mortal.

But where is the commons? I mean that seems like the ridiculous part. As long as people are not responsible for the choices of others, and can make their own choices, there is no "commons" over which to have a tragedy.

The commons in this case is ultimately knowledge or the lack thereof. Knowledge of what's likely to work and what's likely to hurt.

Very good point Robert.

It is about that exactly. Competition for knowledge.

Not bad because look at this wonderful thing.

The government did not create it.

This is the same murderous reasoning behind single-payer. Not a government option for people, but they shut down private service because their shiny command and control model needs your dollars, too!

It's like Social Security saying, "What we provide is what you get, and the moment you retire, all your savings go to us."

"The new rules were "opposed by cancer research organizations, patient advocates and pharmaceutical companies, who argue it would add an unnecessary level of regulation and deny many patients access to potentially life-saving treatment," reports Michigan Capital Confidential, a nonprofit journalism outfit covering Michigan politics."

But, but, it's for the children! Oh wait, wrong topic....

Can we the people set up certificate of need councils for the number of stupid politicians?

CON should be repealed by all states. It does not improve outcomes nor allocation of resources.

That said as has been pointed out this is a very complex process taking weeks and requires intense monitoring. You need a team capable of handling all of that. Not just any oncologist your hospital should be doing this. ThomasD has pointed out all of the major issues.

So the cynical part of me about why this would be blocked by the big center doing this. Say University Hospital has been doing a CAR-T program. St. Elsewhere on the other side of town has an oncology group on the other side of town that wants to start this.

So they may have someone who did a fellowship or some additional training, they might even be talking with Dr. Valdez who is running the program at University. University does not want to lose the patients and does not want to lose Dr. Valdez who will take his patients with him.

So while doing something like this requires very rigorous standards the whole CON process leads to cronyism.

But, but... It's badass.

Indeed, it is so badass that, done improperly, it could out and out kill people.

And, in today's litigious - and third party payer dominated - society, that often means an overabundance of caution - better to not save a few people but still develop a strong track record of saving others than the alternative of saving more people at the expense (and horribly business killing publicity) of killing a few.

Big boys are always content to play it safe, and if that means squashing the little guys, so be it.

Funny that Reason doesn't see it that way when addressing anti-competitive behaviors in the publishing. world...

By "doesn't see it that way" I really mean "doesn't see any problem."

Indeed, it is so badass that, done improperly, it could out and out kill people

So it is like every single other medical procedure.

Not really. With most other procedures we already know what kills and what doesn't. We barely understand the immediate effects of these modalities, much less any long term risks.

As I noted below, I'm pretty sure the long term effects of recurrent cancer are guaranteed to be worse.

The number killed from rushed treatments has an unfortunate snake oil connotation, while the millions dead over the decades because medical tech is lagging behind where it would have been don't count.

A politician can get a lot more hay out of a few bodies in front of the camera than a million who died needlessly under a laggard status quo.