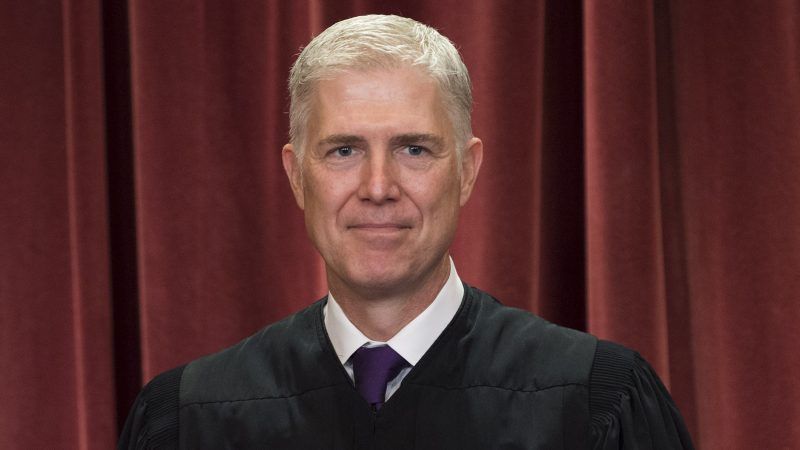

Neil Gorsuch Disappoints Libertarians, Votes To Uphold Protectionist Liquor Law

The conservative justice would have permitted a nakedly anti-competitive regulation.

Supreme Court Justice Neil Gorsuch has generally received high marks from libertarian legal observers since joining the Supreme Court in 2017. That is due in part to Gorsuch's hawkish stance in Fourth Amendment cases, as well as to his sharp rulings against what he sees as executive and legislative malfeasance.

But Gorsuch had very few libertarian admirers this week when he voted in favor of upholding a nakedly protectionist state liquor law. In fact, Gorsuch's reasoning in the case put him directly at odds with a significant number of libertarian legal thinkers.

The case is Tennessee Wine & Spirits Retailers Association v. Thomas. At issue was a state law imposing a two-year state residency requirement on all applicants seeking a license to operate a liquor store. According to the Supreme Court's ruling, because this measure "blatantly favors the State's residents and has little relationship to public health and safety, it is unconstitutional."

Gorsuch disagreed. The Constitution allows "each State the opportunity to assess for itself the costs and benefits of free trade in alcohol," he insisted, even if that assessment results in "reduced competition and increased prices." As for the majority's view that the Tennessee regulation served no valid public health or safety purpose, Gorsuch countered that the protectionist measure might well benefit the public by "raising prices, and thus reducing demand" for alcoholic beverages.

Among the winning parties in Tennessee Wine & Spirits are a couple named Doug and Mary Ketchum, who own a store called Kimbrough Wine & Spirits. The Ketchums ran head first into the protectionist state law when they purchased that business in 2016, shortly after moving to Memphis from Utah. They retained the libertarian lawyers at the Institute for Justice (I.J.) to represent them in their legal fight against the Tennessee regulation.

In its brief to the Supreme Court, the I.J. legal team stressed a constitutional doctrine known as the "dormant Commerce Clause." In effect, this doctrine holds that the Commerce Clause, in addition to authorizing Congress to regulate economic activity between the states, also forbids the states from enacting any interstate economic barriers of their own.

"History has repeatedly demonstrated that states will not hesitate to engage in 'low-level trade war[s]' unless the judiciary stands ready to vigorously enforce the Commerce Clause's nondiscrimination principle," the I.J. lawyers argued. "In the face of persistent and creative state efforts to protect local economic interests, enforcement of that principle is the surest means of preventing the economic Balkinization that the Framers sought to avoid."

To understand what the framers sought to avoid, consider the words of James Madison. In Federalist 42, Madison explained that one of the main purposes behind the Commerce Clause was to clear away the various tariffs, monopolies, and other interstate economic barriers that the states had erected under the Articles of Confederation. In other words, one of the objectives of the Commerce Clause was to help create what we might refer to today as a domestic free trade zone. "A very material object of this power," Madison wrote, "was the relief of the States which import and export through other states from the improper contributions levied on them." Tennessee's protectionist liquor law fits that Madisonian definition of "improper."

This week's ruling in Tennessee Wine & Spirits is not the first time that the libertarians at the Institute for Justice have argued and won a dormant Commerce Clause case at the Supreme Court. In 2005, the I.J. team was among the winning litigators in Granholm v. Heald, which struck down protectionist state laws banning the direct sale of wine to consumers from out-of-state wineries. As I.J. lawyer (and current Arizona Supreme Court justice) Clint Bolick said during oral arguments, "Our clients," a small, family-run winery, "cannot compete with the liquor distributors in the political marketplace…. They can, however, compete in the economic marketplace. The Commerce Clause protects that right, that level playing field." According to Bolick, the regulations at issue deserved to be struck down because "the state is engaged, not in legitimate regulation, but in economic protectionism."

The Supreme Court agreed with Bolick.

Which brings us back to Gorsuch. In his Tennessee Wine & Spirits dissent, Gorsuch dismissed the dormant Commerce Clause as an "implied doctrine" and criticized it as a source of "judicial activism." In contrast to the position championed by the Institute for Justice, which called for the judiciary "to vigorously enforce the Commerce Clause's nondiscrimination principle," Gorsuch suggested that the Court should have stayed out of the matter entirely. "The regulation of alcohol wasn't left to the imagination of a committee of nine sitting in Washington," he wrote, "but to the judgment of the people themselves and their local elected representatives."

Thankfully for the libertarians, Gorsuch's view was the losing one this time around.

Editor's Note: As of February 29, 2024, commenting privileges on reason.com posts are limited to Reason Plus subscribers. Past commenters are grandfathered in for a temporary period. Subscribe here to preserve your ability to comment. Your Reason Plus subscription also gives you an ad-free version of reason.com, along with full access to the digital edition and archives of Reason magazine. We request that comments be civil and on-topic. We do not moderate or assume any responsibility for comments, which are owned by the readers who post them. Comments do not represent the views of reason.com or Reason Foundation. We reserve the right to delete any comment and ban commenters for any reason at any time. Comments may only be edited within 5 minutes of posting. Report abuses.

Please to post comments

Maybe he just hates the Commerce Clause.

In other words, Gorsuch was arguing that the law did not sufficiently impact interstate commerce to justify interfering with Tennessee's state sovereignty. The policy reasons why this law is bad were irrelevant to his vote on the ruling.

And the 21st amendment says “The transportation or importation into any state, territory, or possession of the United States for delivery or use therein of intoxicating liquors, in violation of the laws thereof, is hereby prohibited.” This is not a slam dunk commerce clause case. The 21st amendment seems to give an exception to the commerce clause.

So they call you MISTER Tibbs, do they?

The 21st Amendment modifies the Constitution. The Constitution includes the Commerce Clause. Thus the 21st Amendment modifies the Commerce Clause too.

I think that is what Gorsuch figures. Where this goes off the rails, of course, is that the Commerce Clause was so heavily re-interpreted AFTER the 21st Amendment, it's hard to come up with any logical fresh interpretation; or rather, every fresh interpretation is built on that same quicksand, and it says whatever any aspiring authoritarian wants it to say.

>>>come up with any logical fresh interpretation

like what it was meant to be? ~~~Filburn

But this case had nothing to do with the transport of liquor into Tennessee. I don't think you can say the 21st Amerndment implies anything about the state's granting of liquor licenses any more than you can say Congress's lack of regulation in an area implies anything about the state's power over commerce in it.

But what I think you do have here that gives this a federal nexus is that this is a case of rights, privileges, or immunities withing a state.

I agree with Mickey Rat. While this was a bad law, Gorsuch's reasoning is arguably sound, even if I'm happy that the SC struck the law down. Gorsuch has been a surprisingly great SC, and I respect him. That doesn't mean he's gonna vote in "our" favor every time.

Agree with the others.

Gorsuch is right here.

Looks like libertarians want more power for The State, seeing as the commerce clause is what's used to grant the fed all sorts of ridiculous scope

Exactly. Gorsuch is protecting the state's right to regulate any product or service intrastate.

21st Amendment, Section 2:

The transportation or importation into any state, territory, or possession of the United States for delivery or use therein of intoxicating liquors, in violation of the laws thereof, is hereby prohibited.

The 21st Amendment gives the federal government power to assist states that amend their state constitutions and ban alcohol and then persons transport or or import alcohol into said state.

This should illustrate how much weaker the Commerce Clause powers should be as it stands in the US Constitution.

But the commerce clause is a real part of the Constitution and means something.

Gorsuch may be right and the 21st amendment allows states more control over liquor related things. But forbidding people from out of state from owning a business in a state does seem like something that might be a valid interstate commerce thing.

Using the commerce clause to prevent states from restricting commerce is what it was intended to accomplish. The fact that it has been abused doesn't mean it should never be used for its intended purpose.

The Commerce Clause is a very real part of the Constitution that means something (not as much as it's been read to mean in modern times, but still something significant). The dormant Commerce Clause, however, is not an explicit part of the Constitution. The Commerce Clause gives Congress the power to pass laws regulating interstate commerce while the dormant Commerce Clause governs situations where Congress has not passed any applicable laws. It's a relatively free-floating doctrine based on the implications of several provisions of the Constitution but not actually included in the text (which is why many originalists are not particularly fond of it).

Congress hasn't passed any laws applicable to this dispute, which is why the dormant Commerce Clause was at issue, not the Commerce Clause. If Congress had passed a law conflicting with Tennessee's law, the analysis would have been different (under the Commerce Clause itself), even if the result would have been the same.

Good point, and explanation.

I don't see this as a Commerce Clause issue, but rather a 14th Article of Ammendment Priviledges and Immunities issue.

If I can own a liquor store in my home state of Arkansas, how can Tennessee prohibit me owning one in Tennessee? If Charlie can own a liquor store in Tennessee, then I can.

WHO are the goverment of the State of Tennessee to dictate that one must satisfy some residency requirement to own a liquor licence, as long as the applicant is a resident of Tennessee at the time of getting the licence, and thereafter as they manage the business under that license?

Do they have similar requirements for, say, a filling station, mechanic shop, car dealership, grocery store, landscape business?

The Fourteenth Amendment Privileges or (not and) Immunities Clause as currently enforced is nowhere near that expansive--it has been held to protect only distinctively federal rights. You would have better luck with the Privileges and Immunities Clause in Article IV of the Constitution itself. But the Twenty-First Amendment gives a plausible hook for more restrictive regulation of liquor stores, which is also what distinguishes them from your other examples.

I was reading to find where I should be opposed. I don't like the law, but the US Constitution doesn't prevent it. If anything it is an intrastate issue and not tied to any interpretation of the commerce clause. I don't always agree with the results of Gorsuch's decisions but can't fault his reasoning especially from a Libertarian/Constitutionalist perspective

"No State shall make or enforce any law which shall abridge

the privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States." Here, the right to engage in a lawful occupation...

I guess I don’t see how Tennessee having a law that says that a business in Tennessee must be run by a resident of Tennessee affects interstate commerce.

Probably because you don't see how manufacturing a gun in Montana, from parts sourced in Montana, stamped with the words "not to be sold outside the state of Montana" can affect interstate commerce. But it does.

So a totally different situation is interstate commerce therefore so is this. Yeah, that makes sense.

$parkY, LongtoBefree is cracking on you and you're too stupid to realize it.

Poor lovescontroll69 has wandered into a conversation that’s above him and feels the need to whine about it.

SparkY’s life is on track now.

He gets to increase reason web traffic.

The couple were residents of TN.

The law was that you had to be a resident for 2 years before applying for a liquor license, and that to renew said license (an annual thing), you had to be a resident for 10 years. So they could get a license for a year (after 2 years of waiting), then could not legally renew that license for another 7 years.

That’s the very definition of protectionism.

That’s the very definition of protectionism.

You’ll get no argument from me that it’s protectionism. However, Gorsuch seems to be making a valid point that it’s also a state’s right to make laws that only affect that state.

As a resident of TN who hats the ridiculous anti-competitive anti-freedom myriad of alcoholic beverage laws and regs in most states, the law was 100% Constitutional.

Most alcoholic beverage regs are designed to enrich the cartel of distributors at everyone else's expense.

That doesn't mean judges should strike down laws they don't like with no legal justification. That is worse than the cronyism and corruption of the Liquor Lobby

It may or may not, but check out article 3, and as if that weren't enough, amendment 14. How far do you have to twist this to make a liquor license not be a "privilege" counts as such, and reserving them for 2+ year residents of the state as a violation of the applicable parts of the US constitution?

I meant article 4 of the US Constitution, not 3.

Reason loads so much onto a page, I seem to have to wait forever to regain control of a cursor here.

Thankfully for the libertarians, Gorsuch's view was the losing one this time around.

FFS Root, I thought you were above results oriented evaluations of SCOTUS decisions. The dormant Commerce Clause is an awful doctrine of invented judicial authority, and I'm very glad, as a libertarian, that Gorsuch and Thomas shit all over it.

Yeah, Libertarians supporting government barriers to individual liberty is so Libertarian.

Note: Not to be conflated with barriers along the border.

You're correct that there's no direct tie between being a libertarian and being an Originalist. BUT...so what? There's still a principles argument. And being a results oriented "maximal liberty", regardless of Constitutional reasoning, isn't a particularly principled position.

And being a results oriented “maximal liberty”, regardless of Constitutional reasoning, isn’t a particularly principled position.

It's the only principled position. It's certainly far more principled than putting the whims of legislators before individual rights simply because "the law", i.e. FYTW.

Actually, it's just as unprincipled to say "I can't find any reason this law is unconstitutional, but I don't like the law, therefore it's repealed." as it is to say "This law is unconstitutional, but I like it, so it's not going anywhere."

"The dormant Commerce Clause is an awful doctrine of invented judicial authority, and I’m very glad, as a libertarian, that Gorsuch and Thomas shit all over it."

While I appreciate the effects of the Dormant Commerce Clause, it does appear to be largely a judicial creation. There's certainly nothing surprising, or disappointing, about the two committed originalists on the Court rejecting it.

After the "penal-tax" decision, I'm not sure the Court can disappoint me anymore. All they can do is surprise me on the up-side.

Like short comments? 🙂 🙂 🙂

Up yours!

There!

How is saying that states have more power than the federal government, in an area where the US Constitution does no give power to the federal government, not Libertarian?

Like Great Britain quarantining incoming pets, maybe states should quarantine 'outsiders' for a period of time to be sure they aren't contaminated by socialism.

Libertarianism is about individual rights, not states rights.

Federalism isn't a libertarian principle. Doesn't matter which government is shitting on your rights.

Like Great Britain quarantining incoming pets, maybe states should quarantine ‘outsiders’ for a period of time to be sure they aren’t contaminated by socialism.

I'm pretty sure that is a legit commerce clause issue where the feds could rightly step in.

Poor Zeb thinks tiny and limited government is Not a libertarian principle.

Mixing anarchy and libertarianism again.

Gorsuch was standing up for the rule of law - a principle which, in constitutional interpretation, tends to favor liberty more often than not.

But not in this case. The 21st Amendment seems on its face to allow protectionist booze laws. This is a case where the Constitution's text - and its original intent in letting prohibition laws prevail over the dormant commerce clause - leads to an anti-liberty result.

Given the tendency of the Court to write inconvenient provisions out of the Constitution, Gorsuch takes the welcome position of applying these inconvenient provisions. We may have occasion to be grateful for this when it comes time to protect, say, jury trial or the right to bear arms.

---"Gorsuch countered that the protectionist measure might well benefit the public by 'raising prices, and thus reducing demand' for alcoholic beverages." ---

I though the justification for more protectionism was to favor local, domestic producers thus helping the economy, and not to 'reduce demand'. I guess the serial rapist-in-chief lied to me...

They were aware that protectionism made the "protected" product more expensive and less available - feature not bug for prohibitionists who were allowed to keep state prohibition in exchange for abolishing federal prohibition.

bought a liquor store in a state w/2 year residency requirement for liquor license ... nice diligence lucky they won.

You missed the 10 year residency requirement for renewing a liquor license, which requires annual renewal.

Fun times. Live in Tennessee for 2 years and you can own/operate a liquor store for exactly one year. WTF?

On the other hand, the 21st amendment pretty much exempts alcohol from the dormant commerce clause.

Originalism is so weak it couldn't withstand the faintest whiff of Tennessee whiskey. The Twenty-First Amendment survives mostly as a testament to judicial hypocrisy.

wait, it is hypocritical for judges to acknowledge a constitutional amendment? Meaning a judge's job is to ignore Constitutional amendments? What kind of backwards ass bumpkin thinking is that? Or do you just not understand the plain meaning of the words you e-vomit forth here??

You really buried the lede on this one.

“enforcement of that principle is the surest means of preventing the economic Balkinization that the Framers sought to avoid.”

Putting that in a brief alone warrants an adverse ruling. Jesus.

Can you elaborate?

Gorsuch is right on this. Federalizing intrastate commerce is NOT a libertarian position. Reason is wrong here, and the author Damon Root is wrong.

Just because we do not like the underlying law here - and I do not - doesn’t mean that the libertarian position is to accrue more power to the federal government.

Looking at the comments here and on Facebook shows that far, far more libertarians agree with me than with Damon Root.

Please do not pretend to speak for “libertarians” with utterly misguided opinions like these. Thank you.

Gorsuch argued for localism versus globalism .

No, he argued for applying the law as written rather than the law as made up by judges. The dormant Commerce Clause is a fictional part of the Constitution, which Gorsuch declined to follow the majority's determinatin to pretend it existed.

A proper judge rules according to the law, not according to his policy preferences. I hav no doubt that Gorsuch thinks this Tennessee law is terrible as a policy matter. But not only is it not his job as a judge to change it, it's his job as a judge not to change it.

How to find the solution for this tracking best earphones under 500 like with new prices.

not disappointing libertarians...lol...cause that's important

The law is intended to make sure liquor retailers are residents and not large retail chains like Total Wine. Dont forget Jack Daniels is distilled in Tennesee yet cannot the sold in the county where the factory is housed because it is dry. The reason people outside the south freak out about liquor laws is they dont understand the one thing all Southerners grow up knowing... liquor is banned or sold based on the power of the local Southern Baptist church. If a community has a large and strong Baptist population, it will be dry. The Baptist church is always the largest and most prominent building in every small town from Virginia to Texas. There is a good reason the entire region is called the Bible belt.