These Three Cities Spent $70 Million on Stadiums to Lure Minor League Baseball Teams. They All Struck Out.

Across the country, minor league teams are exploiting civic enthusiasm for small town sports.

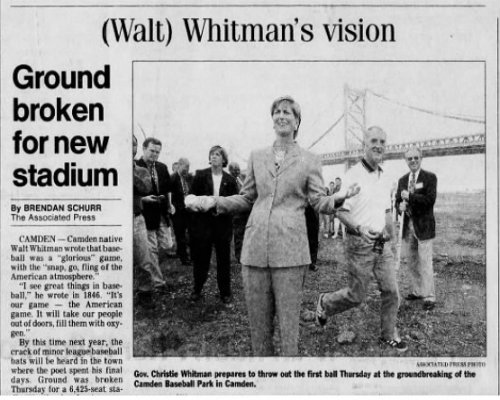

It was a perfect day for baseball—warm but not too hot, with a light breeze blowing, and clouds blocking out the June sun—when Gov. Christie Whitman, ball in hand, announced that a new stadium was exactly what Camden needed to turn the corner.

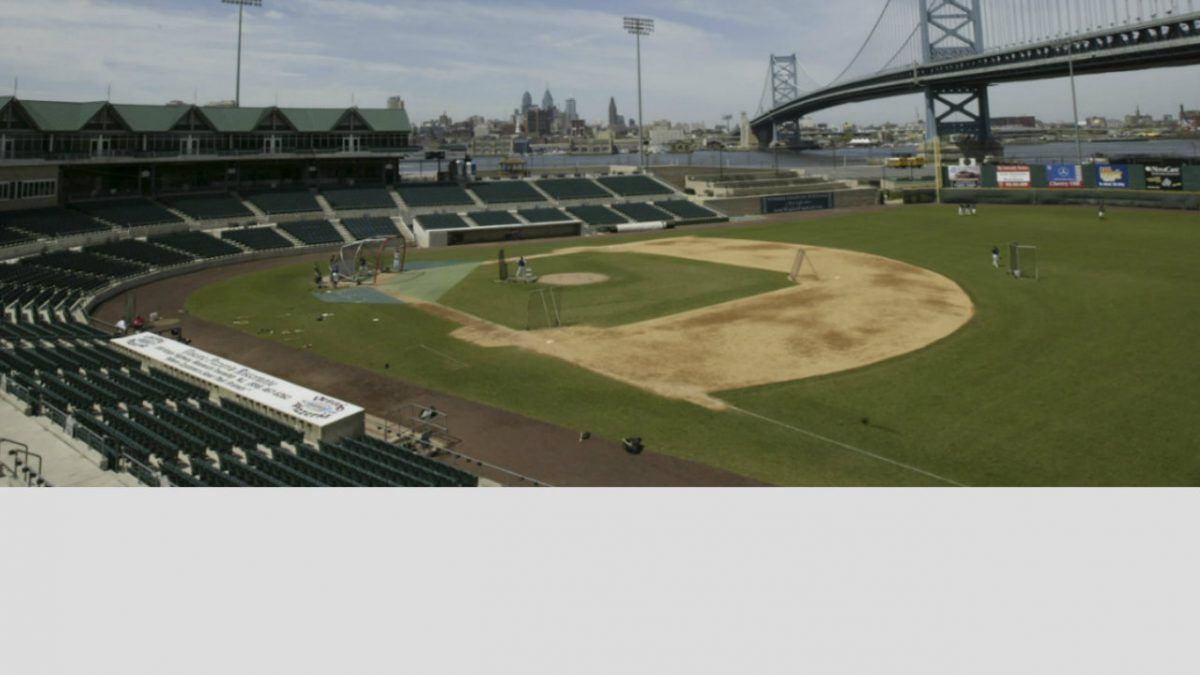

"This ballpark will be another step in giving this city, which has seen its share of tough times, a second chance," announced the then-governor of New Jersey, while standing in the shadow of the mighty Ben Franklin Bridge along the banks of the Delaware River.

"I'm very pleased to be here for the groundbreaking of another stadium in what has become a long list of outstanding baseball parks across our state."

Under Whitman's watch, New Jersey embarked on an unprecedented minor league baseball stadium building spree, as the state tried to turn itself into a hotbed for minor league baseball. From 1994 through 2001, seven new minor league teams took root in the state. Some were new franchises, while others relocated from out-of-state. Some played in leagues directly affiliated with Major League Baseball, while others played in independent leagues outside the MLB farm system. All of them played in brand new stadiums largely—and in some cases entirely—funded with public money.

The state's riskiest bets were placed on three franchises in the fledgling Atlantic League. Teams in Atlantic City, Newark, and Camden were gifted new stadiums with generous leases, built on dreams about turning those struggling cities into attractive destinations for visitors and families. But for all the talk of economic growth, second chances, and civic revitalization at the time, the two decades since have provided a stark lesson: baseball stadiums are not the key to rebuilding struggling American cities.

Today, all three Atlantic League teams are long gone. Stadiums that cost taxpayers tens of millions of dollars apiece sit empty or have been torn down in pursuit of what civic officials see as the next sure thing in economic development—all while the bonds used to build them are still being paid off. The Atlantic League never turned New Jersey's struggling cities into baseball Meccas, but it continues seeking public largesse elsewhere. Politicians have yet to learn the lesson.

If You Build It, Will They Come?

At the groundbreaking for the stadium in Camden, then-governor Whitman reached for the most obvious of all baseball clichés.

"These partners have heard the message from the movie Field of Dreams: 'If you build it, they will come,'" Whitman said. "Soon we will see a field of dreams right here in Camden, and my prediction is they will come."

That 6,400-seat stadium was, by all accounts, a pretty great place to catch a ballgame. Built along the banks of the Delaware River in the shadow of the majestic Benjamin Franklin Bridge, which connects Camden to Philadelphia, Campbell's Field offered better views of the Philadelphia skyline than the major league ballpark trapped in a sea of parking lots at the city's southern frontier. It offered both staples of minor league baseball: cheap tickets and cheap food. Former major-leaguers like Pedro Feliz and Jose Lima played out the twilight of their professional careers in Camden. Bob Dylan performed in the stadium once. In 2004, it was honored by Baseball America magazine as the best ballpark in America.

The $24 million stadium was part of an economic development effort that included a slew of boondoggles. There was also a $52 million aquarium, and a new light rail line linking Camden to Trenton, the state capital that's about 20 miles north along the Delaware River. Camden and Philadelphia even sunk more than $18 million into designing an aerial tram to cross the river—nearly as much money as to took to build the ballpark in Camden—before abandoning idea. For all that spending, the only physical part of the project to be built is an odd, Stonehenge-like concrete arch that still stands along the Philadelphia bank of the river.

"The tram was almost a requirement for this deal," Riversharks owner Stephen Shilling told the Courier-Post, a South Jersey-based paper, in 1998 when local and state officials were debating the proposed funding for his team's stadium. "The reality is some people are afraid to drive to Camden after dark. I'm confident a stadium will have a big economic impact on the city."

In retrospect, it might not have been a great idea to build a baseball stadium in an area that people are afraid to visit after dark. Most baseball games are played in the evenings, and they generally don't end until well after sundown.

Initially, the great views were enough to convince baseball fans to flock to Camden, a city probably most well-known for consistently ranking among the poorest and most violent in America. But after an initial surge of interest, attendance dropped to about 3,000 per game—decent for independent league baseball, but less than half of the capacity of Campbell's Field.

That's nowhere near enough for a stadium to be an engine of economic development, says Victor Mattheson, a professor of sports economics at The College of the Holy Cross. "That's about 250,000 fans per season—or about the number of people who will visit an eight-screen movie theater over the course of a year," he tells Reason. "But no one in their right mind would say 'you know what the solution to all of Camden's problems is: a new movie theater.'"

Not that he's advocating for such a thing, but in some ways a movie theater would be a better public investment, Mattheson points out. Movie theater jobs are year-round, not part-time for only 70 or so games per season. And a movie theater generates consistent traffic for nearby businesses to potentially take advantage of, while a baseball stadium brings people to town only on game days and only immediately before and after the game.

In Camden, it was the bridge just beyond center field that paid for much of the stadium. About 100,000 vehicles cross the Ben Franklin Bridge on an average day, paying tolls of at least $5 each—trucks and busses pay more. That toll money goes to the Delaware River Port Authority, which also operates three other bridges in the Philadelphia area, and a portion of it helped pay for the $6.5 million that the DRPA put towards the Camden stadium. In other words, people driving past the Riversharks' stadium—people who in all likelihood never bought a ticket to see the team play—ended up contributing more to the cost of Campbell's Field than the team ever did.

Every one of those dollars could have gone elsewhere—to city services like police, or to schools, or to tax cuts to attract businesses to Camden.

When the city tried to get the team to pay more towards the cost of maintaining the stadium, the Riversharks' owners balked, then bailed. The team abruptly moved to Connecticut before the 2015 season, leaving a beautiful but useless stadium behind.

Rick White, president of the Atlantic League since 2014, told Reason that the league and team tried to renew their lease in Camden but were unable to do so.

"It became clear that government officials far beyond the municipality had their eyes on that property," White said. The team struggled to succeed in part because of the economic woes of Camden, White said, comparing Camden's situation to what happened in Bridgeport, Conn., where another Atlantic League team folded two years ago after 19 seasons. "At the end of the day, a once-beautiful ballpark had not been maintained to the level it should have been. That was the obligation of the municipality, and not the ball club."

The "Walt Disney" of Bad Baseball in Struggling Cities

It's unlikely that the Camden Riversharks—along with the rest of the Atlantic League—would ever have existed without the influence of Frank Boulton.

A successful bond trader and avid baseball fan who retired from Wall Street in 1999, Boulton has worn many hats during the Atlantic League's two decades. He founded the league in 1998 and has served as its CEO ever since. He also owns the Long Island Ducks—one of the league's most successful franchises, both in terms of on-field performance and attendance. At various times, he has also partially or entirely owned three other teams in the league.

That the Atlantic League has survived for 20 years is a testament to Boulton's ability to promote his brand, to spin repeated failures as signs of coming success, and to continually convince civic leaders to pay the bill for his hobby.

"I became a student of minor league baseball," Boulton told Forbes for a fawning 2013 profile that credited the Atlantic League's success to his "attention to detail," even though the CEO himself provided a better explanation. "I started to see this critical mass—areas that wanted baseball," he explained. "Cities were getting ready to make public investments in it."

Boulton proved to be very good at convincing cities to make those investments. Almost every newspaper story about potential Atlantic League franchises and stadiums for the past 20 years dutifully quotes the league CEO predicting success. "There's a lot of cities courting us," he told The Morning Call in Allentown, Penn., in 1999. An Associated Press article from the same year about the fledging league describes Boulton's vocabulary as "Disneyesque" with promises of "major-league amenities on a minor-league scale" and referring to fans as "guests."

(This article uses "minor league baseball" as a catch-all term to describe both officially MLB-affiliated minor league teams and independent league teams like the Riversharks and Ducks.)

That salesmanship meant that, even as some Atlantic League teams struggled and failed, other cities—usually small, economically struggling ones, stepped up. By 2005, three of the league's six founding teams were gone, but the league had actually grown in size. When city officials in Lancaster, Penn., were preparing to put up $20 million to build a stadium for a new Atlantic League team in 2001, Boulton told reporters about meeting with local elected officials to "make sure everything was in place" and talked about eventually having 12 teams in his league.

Boulton's boosterism is what you'd expect from any CEO who was dedicated to the success of his company. But city officials bought—and continue to buy—what he's selling without doing the math.

"Any normal business person says 'well, if you can't afford to build your factory, that's not a very good business.' But baseball has convinced someone else to build their factory for them."

Running a successful minor league team is difficult. Running a successful independent league team is harder still. Inside the Major League Baseball farm system, those smaller teams have their players' salaries—probably the biggest expense for most—paid by the big league club that owns their players' contracts. Other expenses, like coaching staff and equipment, are shared with the parent organization. Those benefits don't exist in the world of independent league baseball, where teams really are on their own.

"Very few minor league parks come close to paying for their own rent, mostly because minor league baseball can't generate enough revenue," says Mattheson. With an average attendance of 3,000 per game, a minor or independent team is drawing about 250,000 fans per year. But the mortgage payment on a $25 million stadium is likely to be around $2.5 million annually, Mattheson says, so the team would need to put $10 from every ticket sold towards paying for their home. Without access to the corporate money and television contracts that make major league teams rich, the math simply doesn't work out.

"The mortgage payment costs more than they generate in ticket sales," Mattheson told Reason. "Any normal business person says 'well, if you can't afford to build your factory, that's not a very good business.' But baseball has convinced someone else to build their factory for them."

In that environment, one of the few ways an independent team can survive is by unloading stadium costs onto the public. Asked whether public investments were a mandatory part of the equation in determining which cities the Atlantic League would call home, White told Reason that it is "a component of the equation."

"The model we are most comfortable working with now is to suggest to a community that if they were to invest in the infrastructure and potentially in the ballpark, we can suggest to them developers that can help improve the area around it," White said in a phone interview.

One of Boulton's latest projects is resurrecting the Atlantic League in Atlantic City, where one of the league's founding teams played from 1998 through 2006. The Atlantic City Surf moved to an even more obscure independent league and eventually folded in 2009 after a dispute with the city over who should pay for stadium maintenance. Just 11 years after it had been built with $15 million in public funding, the cleverly named Sandcastle had no working heat or bathrooms, The Press of Atlantic City reported at the time. Atlantic City ended up spending $1.1 million to fix it up as a concert venue and high school baseball field.

Now, the Atlantic League is interested again—even though the underlying financial problems likely remain the same.

"This has absolutely no downside," Atlantic City Council president Marty Small told The Press last year. "If Mr. Boulton delivers…and all the terms are ready to go, we'll have baseball next spring."

"A Huge Mistake"

As predictable and depressing as the failures of the teams in Atlantic City and Camden are, perhaps neither is worse than the stadium project in Newark, New Jersey. Part of the same stadium building spree that produced the Camden ballpark, Newark's stadium was more expensive, used for fewer years, and drew fewer fans during its brief lifespan.

In fact, when the ballpark along the banks of the Passiac River was completed in 1999, it was the second most expensive minor league stadium in the country. The final price tag of $34 million was significantly higher than the $22 million originally appropriated for the project. Essex County taxpayers continue making debt payments of $2 million annually until 2029 to cover the stadium's construction costs, even though the team folded in 2013. While the team existed, it paid just $60,000 per year in rent, Bloomberg reported in 2014.

"It was a huge mistake," state Sen. Richard Codey (D-Essex) told Bloomberg.

Despite a parking garage looming behind the right field wall and its own stop on the Newark Light Rail—every city, it seems, must have both a baseball stadium and a light rail system—the stadium struggled to draw crowds in a market already dominated by the two major league teams in New York City. It probably didn't help that team owner Thomas Cetnar made headlines in 2009 when he was sued by three high school students who claimed he had security guards throw them out of the stadium because they refused to stand for the singing of "God Bless America" during the seventh-inning stretch.

"Nobody sits during the singing of 'God Bless America' in my stadium," yelled Cetnar, a former Newark cop who was removed from the force after being convicted of stealing money meant for undercover drug purchases, according to the lawsuit. "Now get the fuck out of here."

Many would-be fans seemed to listen. In the Bears' final season, they drew a total attendance of just 21,288—an average crowd of just 453 per game, according to Ballpark Digest. Like the team in Atlantic City, Newark had already departed from the Atlantic League by then. The Bears played out their final season in the obscurity of the Can-Am League, where fans didn't even have the chance to see former Yankees or Mets trying to relive their glory days.

That's a far cry from what was promised. Newark's ballpark would be "an important catalyst in the economic revitalization of this city," then-Essex County Executive James Treffinger told the AP in 1998 as the stadium was under construction. As in Camden, the ballpark was just one part of an exercise in civic profligacy that included using public money to build a light rail line and a performing arts center. "We are creating reasons for people to enjoy Newark as a center of entertainment where they can go for beer and a hot dog or white wine and Verdi," Thomas Banker, the executive director of the Essex County Improvement Authority, told The New York Times in 1996, when the stadium plans were hatched.

"A monument to the willingness of desperate cities to throw money at any sports franchise that offered a promise of a return to urban glory, regardless how faint" is how Neil deMause, stadium critic and author of the book Field of Schemes described the Bears' stadium in a 2016 blog post.

It's a monument that won't stand much longer. Newark has approved the demolition of the Bears' former home, as part of a plan to once again redevelop the Passaic riverfront on the taxpayers' dime.

Don't Pin Your City's Economic Hopes on Minor League Sports

The wrecking ball has already come for Camden's once lauded riverfront ballpark. In Newark, the failed baseball stadium still sits empty, but its days are numbered. City officials in Newark have approved a plan to replace the stadium with a mix of apartments, hotels, and office buildings—including and 11-story all-wood office building that might be the tallest such structure in the country, NJ.com reported last year. Though construction has yet to begin, there doesn't appear to be any outcome that would preserve the $34 million stadium. In both cities, officials are looking forward and talking about new developments, more second chances, promising that the next thing will be the thing that finally turns Newark or Camden or Atlantic City back around. At least this time they aren't building stadiums.

"The main lesson of the Atlantic League stadium boom is never to pin your city's economic hopes on minor league sports, and independent minor league sports doubly so," says deMause. "They can be lots of fun to watch as fans, but the odds on a team sticking around for more than a decade or two are only slightly better than that of hitting the lottery."

Elsewhere, the lure of baseball remains strong. When the Riversharks abruptly pulled up stakes in Camden, they relocated to New Britain, Connecticut, and rebranded as the New Britain Bees. They filled a stadium that had been vacated by a minor league franchise—a AA-affiliate of the major league Colorado Rockies—when it skipped town to play in nearby Hartford. The new stadium in Hartford, which Reason has reported on extensively, was another disaster for taxpayers and fans—and proof that MLB-affiliated minor league teams can rip-off cities just as well as smaller, independent league teams.

The Atlantic League never did expand to more than eight teams—and some seasons has been unable to field even that many—but its franchises continue to bounce around wherever they can find cities willing to fund stadiums.

The newest team, the High Point Rockers, began playing this year in High Point, North Carolina. The Rockers are replacing the Bridgeport Bluefish, which folded last year after 19 seasons years in Bridgeport, Connecticut, another northeastern city with myriad fiscal problems and social ills that saw fit to blow millions on a baseball stadium in the late 90s when the Atlantic League was getting started. The Rockers are playing in a college stadium this year, but High Point is in the process of spending $35 million to build a new baseball stadium.

After it opens on May 2 with the Rockers' first home game of the season, the stadium will be used by local high school and college sports too. "We love the community, and we love the way that the ballpark and the club have been configured so that we are not simply utilizing the facility for the purpose of Atlantic League baseball," says White.

White says the idea to put a team in High Point was somewhat serendipitous—but a willingness of city officials to spend money on a new stadium was again crucial.

"We came across a newspaper clipping that mentioned the city of High Point was interested in building a facility that would serve as a recreational asset for the community," White told Reason. "I picked up the phone and talked to city leaders."

"The construction of a stadium is like an anchor for the revitalization and development of a downtown," City Manager Greg Demko told Bloomberg earlier this year. The same piece reported that Atlantic League CEO Boulton said the league "was attracted to High Point because city officials were prepared to build a new stadium."

The stadium, White says, "merged two collective interests."

Show Comments (23)