Ready to Get Off Facebook? Reason Reviews 5 Alternative Social Networks.

Facebook, Twitter, and other mainstream social networks have their issues. Are these 5 platforms viable alternatives?

Facebook can't seem to do anything right.

The social media giant has been the subject of countless negative headlines since the 2016 presidential election and the proliferation of "fake news." With November's midterms rapidly approaching, Facebook has taken steps to course-correct.

Earlier this month, for instance, Facebook deleted 559 pages and 251 accounts that it claimed were in violation of its rules against spam and inauthentic behavior. As Reason's Scott Shackford pointed out at the time, a number of libertarian and police accountability pages were included in the purge.

Some saw this move as a silencing of independent voices. To be clear, Facebook is a private company and has the perfect right to exert full control over its own platform. Even if the social network has a liberal bias—which CEO Mark Zuckerberg denies—Facebook is well within its rights to act on that bias.

It's not just Facebook. Twitter has been accused of leaning too far left as well. Back in July, I reported how the platform was allegedly "shadow-banning" some conservative leaders, meaning their accounts didn't show up when users searched for them in the dropdown bar.

Again, social media companies should not be obligated to treat all political viewpoints equally. Twitter can impose "shadow bans" if it so desires, just as Facebook can ban whichever pages and people it wants off the platform.

In that same vein, unhappy users are more than welcome to leave either social network in search of greener pastures. And many have, with alternative social platforms boasting millions of combined users. None of those lesser-known platforms has anywhere close to Facebook's 2.2 billion active users or Twitter's 335 million. Instead, those platforms say they shine in the areas where Facebook and Twitter fall short, whether that be privacy, decentralization, or a lack of political bias.

With those things in mind, I signed up for accounts on five alternative social networks: Mastodon, MeWe, Minds, Gab, and Vero. I'm not quite ready to delete my Facebook or Twitter yet, though that doesn't mean there weren't things I liked about each site. But no social network is perfect, as my experience with the five platforms highlighted.

Here's what I discovered:

1. Mastodon is all about decentralization. It's also a hassle to use.

Mastodon represented my first foray into the world of alternative social media networks. Founded in 2016 by developer Eugen Rochko, it was launched as a kind of decentralized version of Twitter.

Indeed, Mastodon is in many ways similar to Twitter. Users can blast out hashtag-filled "toots," which have a 500-character limit. "Boosts" are the equivalent of retweets, while a "favourite" is essentially the same thing as a like. Mastodon, like Twitter, is free to use, though the platform's privacy policy emphasizes that it does not sell user data to third parties. It's also ad-free, which probably explains the crowd-funded platform's Patreon page.

The main practical difference between Mastodon and Twitter is that Mastodon is powered by open-source software. It's comprised of many different servers, or "instances," each one catered to a particular interest. The servers are all run independently, and none of them look exactly the same. Since the platform is so decentralized, there's no official mobile app, though intrepid developers have released a variety of "client" apps.

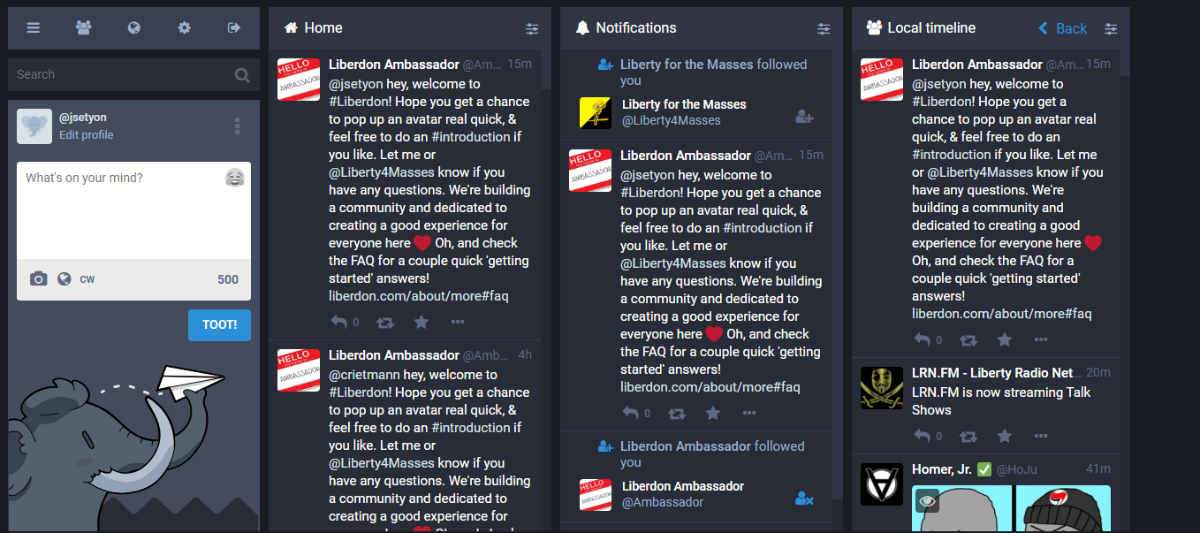

Though each instance is different, the basic four-column layout—at least on desktop—is often the same. On the far left is a column where you can write a status and choose who can see it. To the right is the "home" timeline, which is the feed of content (status updates, boosted toots, photos, articles, etc.) from people you follow. Next is the notifications columns, which alerts you to what others are saying to or about you.

The final column lets users toggle between a variety of options, including the toots they've favorited, direct messages, and their "local" and "federated" timelines. The local timeline is simply a feed of all the posts from a user's particular instance. The federated timeline, meanwhile, includes public posts from everyone that users in your instance follow.

Mastodon is probably a lot of fun if you're tech-savvy, which I'm admittedly not. With over a million users and a handy function that lets you find people you already know from Twitter, making connections isn't all that hard.

But the decentralization part doesn't really appeal to me. At first, I thought one main account on Mastodon.social would let me join as many different instances as I wanted. But my Mastodon.social account ended up only working for that one instance. You can follow users on other instances and see/interact with the content they post. But to fully experience separate instances, you need multiple accounts.

After coming to this realization, I found an interesting instance called Liberdon.com and signed up with a new username. Liberdon is exactly what it sounds like: a community of users posting liberty-themed content.

Here's a screenshot of the Liberdon instance:

I genuinely enjoyed Liberdon, but probably not enough to come back with any sort of frequency. I go on Twitter in large part because I can switch rapidly between trending topics. With Mastodon, it's much harder to do that. The platform is probably great for developers and those with niche interests. To me, the separation of the instances made that too much of a hassle.

2. MeWe's obsession with privacy means there's no one to connect with.

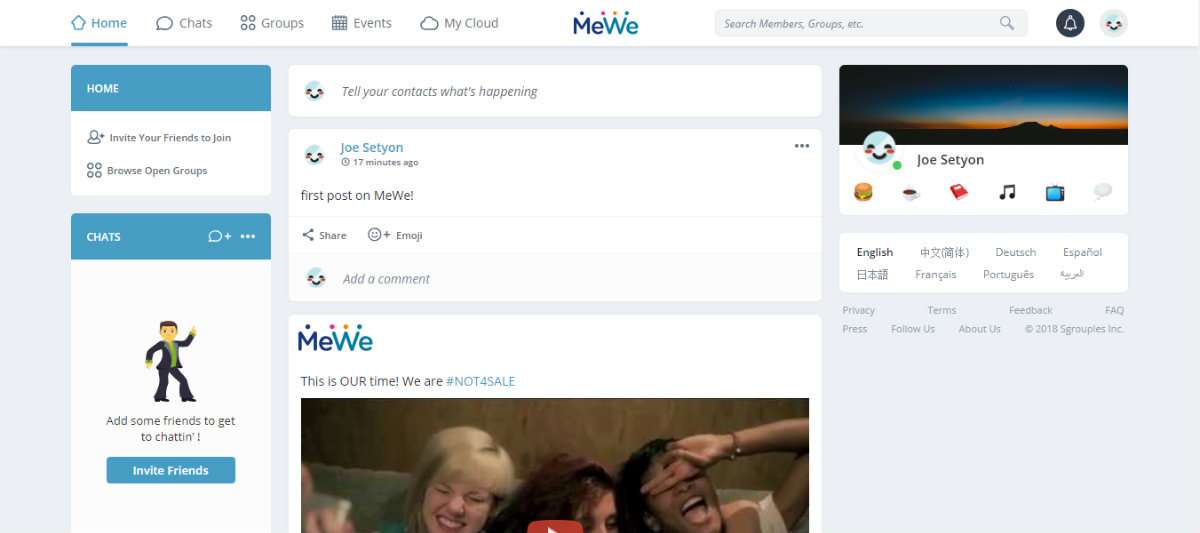

MeWe's about page notes it's a place where users can "connect safely" and "share confidently." The platform does seem to take privacy very seriously. You can choose who sees the content you post, and the site promises that user data is "free from tracking, spying, and scraping."

Like Mastodon, MeWe was launched in 2016, by founder Mark Weinstein. The site is ad-free, and users don't have to pay a cent to sign up. Plus, users own their own content.

So how does MeWe make money? While users receive eight free gigabytes of data storage for photos, videos, documents, messages, and the like, they can pay for up to 500 gigabytes. Other optional services include the ability to create private group apps and print off pictures at Walgreens pharmacies. There's also a paid "Secret Chat" option, which is completely encrypted so that no one—not even the platform itself—can snoop on what you're sending.

MeWe is in many ways similar to its main competitor—Facebook. Instead of friends, fellow users are "contacts" who you can request to connect with. Just like with Facebook, you can add information about yourself, in addition to posting status updates, which might garner a share, a comment, or a simple emoji. The platform also lets you update your contacts as to what food you're currently eating, what beverage you're drinking, what music you're listening to, and what you're watching.

Here's a desktop view of the platform:

MeWe also has an official app that's available for download on the Apple and Google Play Stores.

MeWe's groups, meanwhile, are similar to Mastodon instances in that they're based off of different interests. Each user is able to join many different groups, both public and private ones.

One particularly interesting aspect of MeWe is the option users have to send disappearing messages in the chat. It's a feature akin to what you would find on Snapchat, and it certainly helps further the platform's privacy-obsessed marketing.

My biggest issue with MeWe was my inability to find any friends or acquaintances to connect with. When I tried to use the auto-connect feature to make connections, it turned out none of my phone or email contacts use the site. My lack of MeWe-using friends isn't the platform's fault, but it does make using the network a lot less fun.

Weinstein says more than 2 million people log onto MeWe at least eight times every day. While that's a lot of users, it pales in comparison to Facebook. And if you don't know anyone who's already on the platform, it's going to be difficult to break through the privacy barriers and connect with more people.

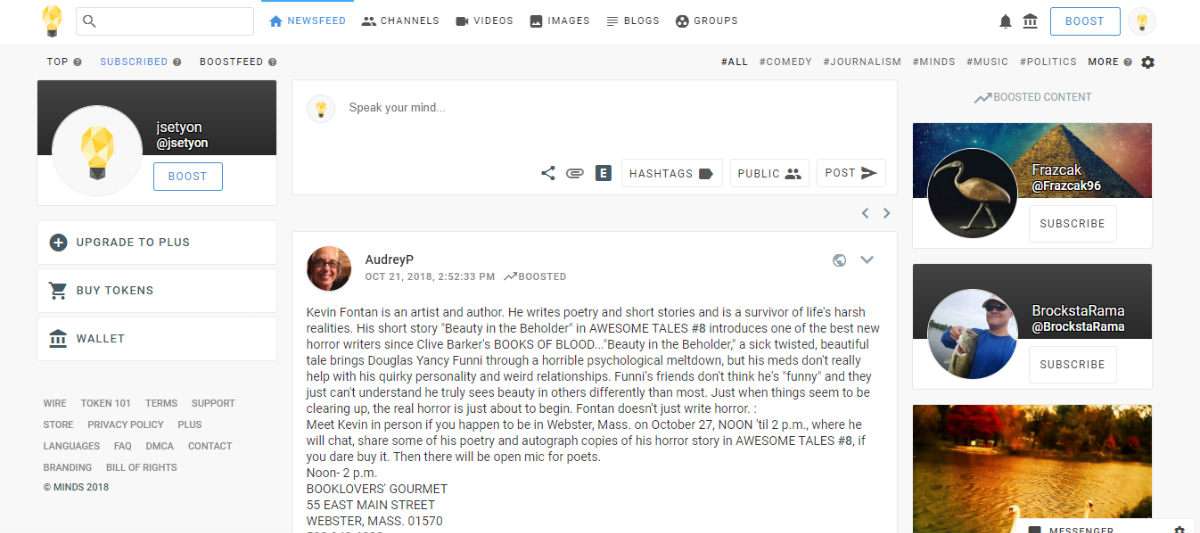

3. I expected Minds to be complicated and cumbersome. It's actually intuitive and tons of fun.

After my experience with Mastodon and MeWe, I wasn't expecting a whole lot from Minds. Mastodon is similar to Minds in that both platforms are open-source and decentralized. And like MeWe, Minds emphasizes privacy. Minds is also trying to differentiate itself from other social networks that allegedly censor controversial viewpoints. "Minds is engineered for freedom of speech, transparency and privacy," the platform says on its funding page, adding that free speech on the network "is limited only by US law."

Founded in 2011 by a group that included current CEO Bill Ottman, Minds is unique in that it runs on cryptocurrency. The free-to-use platform has its own ERC-20 token that it either awards to users for free or sells to them in exchange for the cryptocurrency Ethereum. It's through these exchanges, not outside advertisements, that Minds collects revenue.

Minds' 1.25 million users, each of whom runs their own "channel," can receive some free Minds tokens by interacting with other users on the platform. Minds offers three main services where you can use those tokens.

First there's "Boost," which is the site's in-house ad network. If you want more people to see your content, you can cough up one token in return for 1,000 additional views. Spending tokens on "Plus," meanwhile, buys you access to Minds' premium subscription, where you can remove those in-house ads, become verified, and access exclusive content. Finally, "Nodes" is an open-source feature that lets users create their own unique Minds-based social network.

Moreover, Minds lets users exchange, or "Wire," tokens to each other. Users who choose to monetize their channels can offer exclusive content viewable only in exchange for tokens. Channels can also pay other users to promote their content.

Again, I had little to no hope of being able to figure out how Minds work. But the platform's ease of use was a rather pleasant surprise. I signed up on my desktop, though Minds does offer official mobile apps for your iPhone or Android device. Minds let me create a public profile, with the option to add a bio, as well as information about my channel's goal.

Like Facebook, Minds has a newsfeed that can be filtered in a variety of ways. The "Top" feed presents you with popular content from across the platform, while the "Subscribed" option consists of posts from people you follow. Finally, the "Boost" feed lets you see promoted content. Each feed can be further filtered by clicking on one or more hashtags.

This is how the main homepage shows up on my desktop:

Minds' use of hashtags is probably one of its best features. The hashtags are based off your interests, so if you only want to see content about music or politics, that's your choice. This makes it very easy to seek out relevant content and the users who create it, even if you can't find anyone you already know who's using the platform.

In addition to writing short status updates, users can post images, videos, and blogs, as well as join groups tailored around their interests. Users can decide whether their posts will be free to view or require payment in the form of tokens. Reacting to content is also simple: You can upvote or downvote, add a comment, or share the post.

Minds also has a chat feature that's similar to Facebook's. The main difference is that the chats are encrypted, so Minds recommends that your main password be different from your chat password.

While I understand the appeal of alternative currencies, I've never tried to acquire any of them. Since I'm not into cryptocurrencies, Minds probably isn't a platform I'll use terribly often.

But that doesn't mean I can't appreciate what the site does well. Before I signed up for an account, I thought it would be niche and hard to use. It was actually easy to both navigate the site itself and find interesting content. For folks in the crypto-scene, this platform will likely be very appealing.

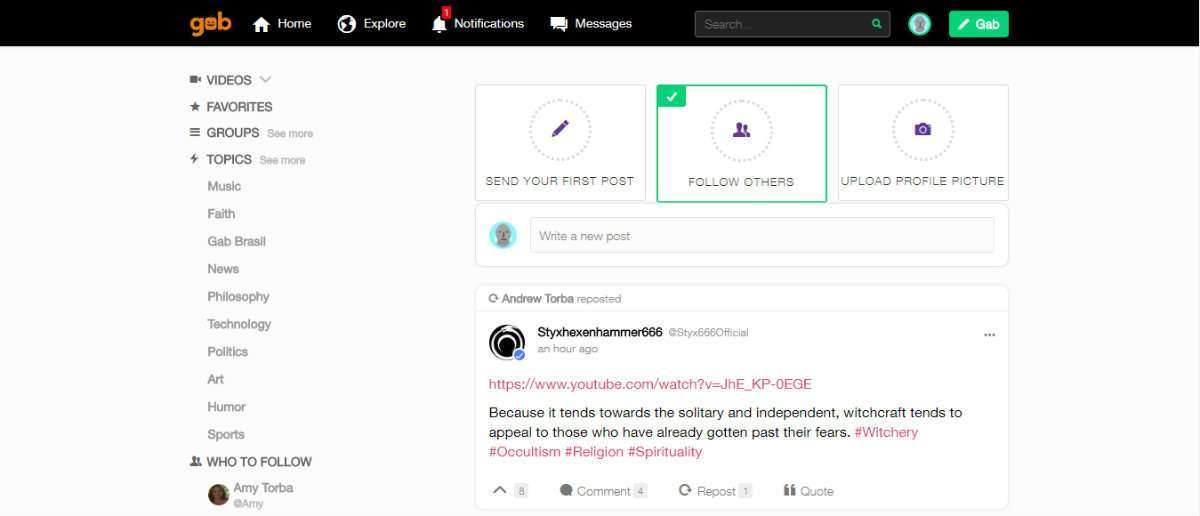

4. Before it went offline, Gab was where the alt-right activists went after they'd been banned from Twitter.

Gab CEO Andrew Torba touts his platform as a way to "free humanity from the chains of Silicon Valley's data silo, psychological manipulation, censorship, and ideological echo chambers." To that end, Torba, who co-founded the social network in August 2016, says Gab's mission is to "defend free expression and individual liberty for all people."

At least for the time being, that mission is on hold. Gab has been in the news in recent days following the revelation that Robert Bower—who's accused of murdering 11 people at Pittsburgh's Tree of Life synaogue on Saturday—frequently posted anti-Semitic content to the platform. Over the weekend, multiple tech companies, most notably the web hosting service GoDaddy, stopped doing business with Gab. Last night, the platform said it would be going offline until it could find a new hosting provider.

Before its temporary demise, Gab really focused on the alleged liberal bias of mainstream platforms like Facebook, Twitter, and YouTube. Gab was both ad-free and free to use, and Gorba says it "must be owned, powered, and funded by you—The People."

Though the platform was free, users could pay $5.99 a month for Gab Pro, which let them become verified, monetize their accounts, save posts for later viewing, create groups and lists based off specific interests, and post live videos.

Compared to the other platforms, Gab has a relatively small user base—just 430,000 people as of April. But there's a good reason for that.

Gab seems to be a gathering place for hardcore conservatives and conspiracy theorists like Bowers. That's not to say everyone on the platform was crazy, but in fighting the alleged left-leaning political bias of the legacy social media platforms, Gab ran into the opposite problem.

As Vice noted in April, Gab was an "echo chamber for the shady tribe of white-nationalists, anti-Semites, pro-lifers and 'meninists' known as the 'alt-right.'"

In my limited experience with the site, that's a pretty accurate description. I didn't follow very many people, so most of the content I saw consisted of posts that were popular across the platform. Those posts were largely about the failing of the mainstream media and other social platforms.

Plus, if my first follower is any indication, the site may also have had issues with keeping porn bots off the platform. The network developed an iPhone app, but was rejected by Apple due to porn on the platform.

For a time, there was a Gab app on the Google Play Store, though it was eventually banned due to alleged hate speech.

From a technical standpoint, Gab was actually easy to use. The app suggested people for you to follow based off who you're already connected with. Like the other platforms, users could join various groups tailored around their interests.

On Gab's homepage, users could see content from the people they follow.

This is what my home feed looked like:

On the left-hand side of the page were various topics (music, politics, news, etc.) that users from around the platform could post content in. Those posts could be filtered chronologically, or based off what was most popular or controversial.

If it's able to find a new hosting provider, Gab may very well be back. Unless you subscribe to a certain radical subset of right-wing beliefs or are interested in seeing the feeds of those who do, though, it's probably not the right social network for you.

5. Vero

Unlike the other four platforms, Vero can appeal to all sorts of people. According to its manifesto, Vero wants personalize your social media experience so your connections aren't just friends or followers. The word vero means true in Italian, and the platform says it's aiming for authenticity: "A social network that lets you be yourself." There are no paid promotions or algorithms, and users see content in the order it was posted.

Launched in 2015 by Lebanese businessman Ayman Hariri, Vero is a subscription-based service, so it doesn't have to sell your information to advertisers. Vero's servers are located in the United Kingdom, and while it claims user data is encrypted, the platform also warns that it's not responsible for any data breaches.

Vero made headlines in February, when it started offering free subscriptions for life to the first million people who signed up. The Vero app, which is the only way you can access the platform, skyrocketed up the charts in the Apple and Google Play Stores. Soon, Vero boasted more than three million users. Due to what the company refers to as "service interruptions we experienced from the large wave of new users," Vero has extended the free lifetime subscription offer indefinitely.

With the massive wave of signups came media scrutiny as well, and the founder has been dogged by accusations of corruption associated with his family's construction business. The controversy slowed Vero's momentum, though it still has plenty of active users. And there is a lot to like. Vero lets you know which of the contacts on your phone are already using the app. Aside from that, you can search for people or pages that you want to connect with or follow.

And there is a difference between connecting and following. For the most part, you follow public figures or pages. That means their public posts come up in your feed, though not vice versa. Connections are people you actually know, though your connections are divided into three "loops": acquaintances, friends, and close friends. When you post content, you can decide how public or private it's going to be based on which loops you allow to see it.

Here's the best part: You know which people are in which loops, but your connections don't.

In terms of in-app experience, Vero is easy to use. Of all the main social networks, it's probably most similar to Instagram in that your feed normally consists of photos, videos, or some other type of media.

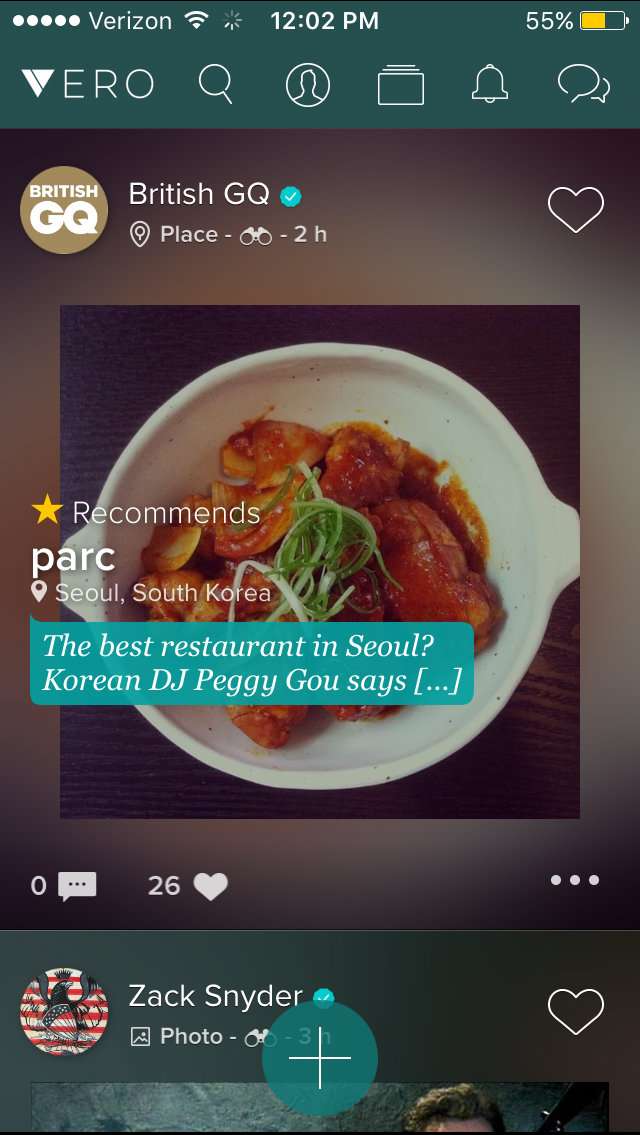

Here's the top of my feed soon after I signed up:

All the posts from you and the people/pages you follow or are connected with are compiled as "Collections." There, they are sorted by date based off the type of post (photo, video, etc.) to make it easier for you to go back and access them later.

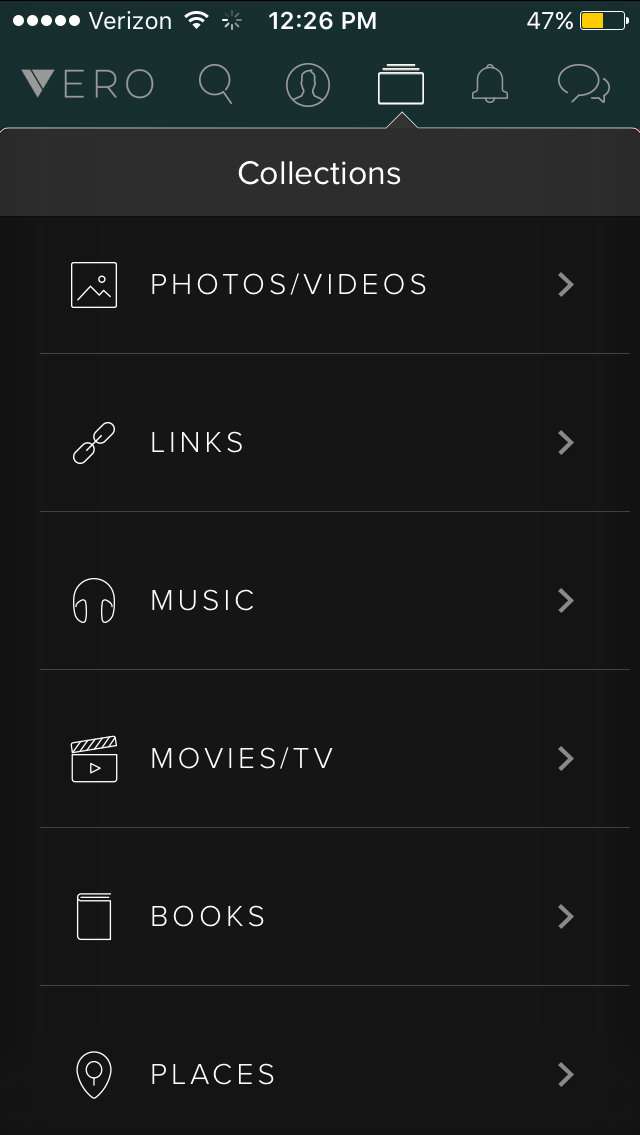

This is what the main "Collections" page looks like:

Though I'm not a frequent Instagram user, I liked Vero. It's an intuitive platform that definitely benefits from the efforts to make it personalized. That being said, I'm not sure I'd be willing to pay for it.

That might be Vero's biggest obstacle: It's easy to get people to subscribe to something when it's free, but it's a lot harder to draw them in when it's not. Vero may very well have a difficult time when it starts charging people to sign up.

Final thoughts: There's a reason these sites don't have more users.

Probably my biggest takeaway from these experiences is that Facebook and Twitter are popular for a reason. Sure, they have their faults, but they're also very easy to use and they appeal to a massive user base.

Sharing a platform with hundreds of millions of users (or 2.2 billion, in Facebook's case), means it's very easy to make connections. No matter what your interests are, there's something for everyone. These alternative sites, on the other hand, seem to cater to niche interests. For those they're trying to reach, that's great, but it significantly decreases the number of people you can connect with. And while Vero isn't targeted to a narrow audience, it remains to be seen if people will actually want to pay for it.

For me, that's all a nonstarter. Facebook, Twitter, and other mainstream platforms thrive in large part because 1) they're free and 2) they make it so easy to reach an enormous number of people.

Do they bombard you with ads and mine your data for profit? Absolutely. But most users—myself included—have decided it's a worthwhile tradeoff. If the balance tips at any point in the future, it's good to remember that everyone has a choice about whether to stay on those platforms.

Show Comments (100)