Why It's So Hard to Get Pervs Out of Politics

Politics is a high-stakes, winner-takes-all game with irresistible appeal to a certain kind of low-quality human being. There are typically only two viable candidates in any national race, and voters have a lot invested in the idea that bad things will happen if their guy loses.

That means that if their guy turns out to be, say, an unrepentant pedophile, there will be plenty of voters who pause for a minute and wonder whether having an unrepentant pedophile in office who will consistently vote the way they want is worse or better than having a non-pedophile who will consistently vote in a way that they believe will undermine the American experiment. Partisan duopoly creates powerful incentives to wear blinders about the flaws of your preferred candidate, and to make excuses for failings too glaring to deny.

In more concrete terms, voters feel compelled to calculate whether a dubious non-consensual boob grab caught on camera is worth accepting in order to get a decade of votes against Republican Supreme Court nominees, in the case of Sen. Al Franken (D–Minn.). Or whether a few sexual harassment settlements paid by taxpayers are a price they're willing to bear in exchange for a vote against Obamacare repeal, as in the case of Rep. John Conyers (D–Mich.). This non-Euclidean electoral geometry was most famously employed on behalf of Bill Clinton decades ago by his feminist supporters, who were willing to dismiss behavior ranging from a voluntary affair with an intern to much more serious allegations of rape and assault, because they believed he would defend women's rights more effectively than his would-be replacements.

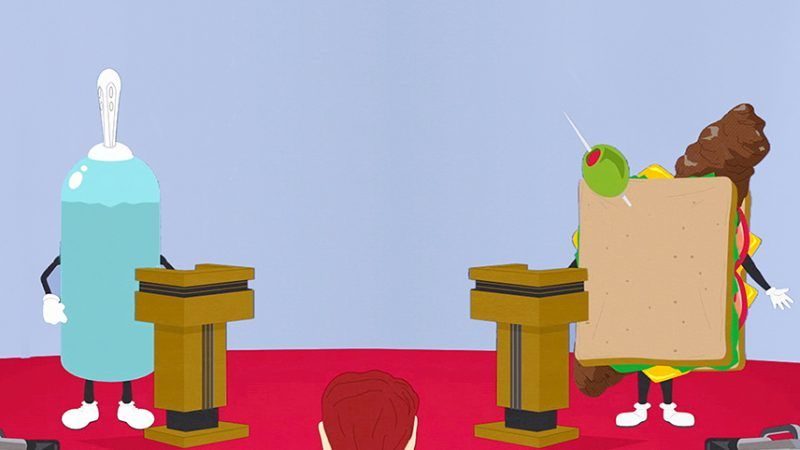

South Park famously depicted formal political debates as moronic shoutfests between a giant douche and a turd sandwich. That's a bit of an overstatement: Not all politicians are disgusting. But when a candidate does turn out to be awful, voters often discover too late that—like visitors to Matt Lauer's office or Harvey Weinstein's hotel room—their escape routes have been blocked off. And simply refusing to participate doesn't help with this particular problem; a write-in vote for "neither" won't prevent one of the major party hopefuls from winning in the end.

Sure, politicians are ultimately answerable to the electorate. They're scared we might not vote for them next time around, and that guides their behavior. But they also know that they've made themselves extremely hard to remove by building all kinds of institutional safeguards for their jobs. Add in decades of gerrymandering that have rendered many districts a sure thing for one team or the other, plus a national party apparatus that controls access to televised debates, and even the scariest charges can be weathered with the right combination of money, partisan panic, and news cycle distractibility.

At press time, it looks like Roy Moore, the Alabama Republican accused of inappropriate behavior toward several teenagers, has narrowly missed being elected to the U.S. Senate. His campaign coincided with a major shift in how Americans process allegations of sexual misconduct.

That shift is metabolizing quickly in the private sector, where producer Harvey Weinstein, actor Kevin Spacey, comedian Louis C.K., journalists Matt Lauer and Leon Wieseltier, and many more were fired (or faced similar sanctions in the marketplace) before they could issue their non-apologies.

One reason for the swift response is that consumer-facing industries—the people who make the stuff we buy, watch, and wear—are highly susceptible to boycotts and other forms of reputational damage. Media companies in particular are subject to the decisions of advertisers, who can easily transfer their marketing budgets to another show, another movie, another product, another publication. An allegation of misconduct that takes off on Twitter or Snapchat can do incalculable damage to a brand's bottom line.

The real difference between public and private sector responsiveness to discovering predators in their midst, though, is the dynamic labor market for talent in the for-profit world. There's always another director who can take over a film project, another CEO who can be hired, another news anchor to step in front of the camera. When Bill O'Reilly washed out, Tucker Carlson popped up like a prairie dog, ready to take his place on Fox News' prime spot. When Charlie Rose got the boot from CBS and PBS after eight women accused him of sexual harassment, Christiane Amanpour shrugged off her flak jacket and slid right into his chair. Diageo summarily killed director Brett Ratner's contract for a line of vanity whiskey after allegations broke against him of casting couch harassment and misconduct. I'm sure if Jell-o Pudding Pops still existed, they would have a new spokesman by now too.

As a result, would-be replacements for boldface names have an incentive to bring accusations to light, whether or not they're true. In late 2017, justice administered in the court of public opinion has been swift. But it is also reversible. A contract that is fairly and legally terminated is one that can be reinstated if reputations or known fact patterns change. No one is in jail; no one even has to wait until the next election cycle. The internet is already rife with think pieces speculating about how long these once-powerful, still-talented men will have to sit in the corner and think about what they did before they're allowed back into the game.

Indeed, it's striking how many of these individuals have quickly confessed when confronted with allegations of misbehavior. The problem, by and large, doesn't seem to be that prominent figures are being wrongly accused. Weinstein, C.K., Lauer, Franken, comedian Andy Dick, and others speedily acknowledged that at least some of the charges are true, presumably in an effort to skip ahead to redemption. Again, this is in contrast to the politicians accused this season, who have more typically followed an "admit nothing until there are no other options" approach.

Cover-ups and slow responses happen in the private sector as well. Boards of directors pay out settlements all the time—sometimes because they believe their guy is innocent, sometime because they think he's worth keeping even if he's guilty, and sometimes because the latter makes it impossible for them to think clearly about the former. But even when things go badly, politicos tend to get softer landings. After looking like he might hang around after the disclosure of past inappropriate behavior, Conyers is being allowed to retire in his own time while attempting to graciously hand off his seat to his son.

And even as people on both sides go down in flames, partisans stick by their teams, debating whether it's more hypocritical for a social conservative (Christian values!) or a social liberal (respect for women!) to commit sexual assault, a back-and-forth likely to soon appear in an episode of South Park as well.

Meanwhile, in a world of at-will employment and tough competition for the best jobs—in the private sector, in other words—there will always be someone to step up when a guy with a good gig topples. Ultimately, businesses are better positioned than political parties to dip into that deep well of talent, and they have a stronger incentive to do so.

Republicans and Democrats work hard to limit our choices when it comes to politicians. But when it comes to the stuff we buy and sell, Americans can meaningfully choose "none of the above."

This article originally appeared in print under the headline "Why It's So Hard to Get Pervs Out of Politics."

Show Comments (104)