Why Are Cops Putting Kids in Cuffs?

Federal funding, zero tolerance, and lack of choice encourage the creeping criminalization of student misbehavior.

When 14-year-old Ryan Turk cut ahead of the lunch line to grab a milk, he didn't expect to get in trouble. He certainly didn't plan to end up in handcuffs. But Turk, a black student at Graham Park Middle School, was arrested for disorderly conduct and petty larceny for procuring the 65-cent carton. The state of Virginia is actually prosecuting the case, which went to trial in November.

Chief among the many ironies of this story is that Turk didn't actually steal anything: He participates in Virginia's free lunch program, which entitles him to one complimentary carton of milk each day. On the afternoon in question, Turk had forgotten to claim his drink during his first pass through the line, so he went back. That's when the trouble started, for a very specific reason: A police officer spotted him and misunderstood what was happening. A police officer. In the cafeteria.

Graham Park Middle School is among the roughly 43 percent of public schools in the U.S. with a School Resource Officer (SRO): a cop specifically assigned to patrol the school. SROs exist ostensibly to keep students safe and classrooms crime-free. But the staggering increase in their ranks over the last several decades has produced thousands of questionable suspensions and arrests. Many due process advocates and education reformers now wonder if the presence of so many cops is actually undermining school discipline.

It shouldn't fall to law enforcement to scold unruly kids: That's a job for teachers, principals, and parents. Unfortunately, bad incentives—including state laws that limit school disciplinary options and federal programs that explicitly subsidize SROs—give schools plenty of reasons to keep hiring cops. Getting rid of those incentives would improve things, but the best solution might lie outside traditional schooling entirely. For students around the country, school choice reforms—which engender new and different ways of thinking about discipline—are already offering a vision for a saner system.

Because there's got to be a better way to teach a kid to wait his turn in the lunch line.

'My Life Could Be Completely Ruined by This' Turk's case stands out because of how petty the state's behavior was, but outrageous examples of police interference in schools aren't hard to find. Take William P. Tatem Elementary School in Collingswood, New Jersey. On the last day of classes last spring, a third-grade boy said something about brownies that another student interpreted as racist. It's likely the kid was talking about chocolate desserts rather than dark-skinned classmates, but that's something the school should have worked out on its own. Instead, it called the cops to investigate an unintentionally offensive remark made by a 9-year-old.

"There was a police officer with a gun in the holster talking to my son, saying, 'Tell me what you said,'" the boy's mother, Stacy dos Stanos, told The Philadelphia Inquirer. "He didn't have anybody on his side."

The investigation did not end there. Collingswood police interviewed the boy's father and referred the case to the New Jersey Division of Child Protection and Permanency, which handles instances of child abuse.

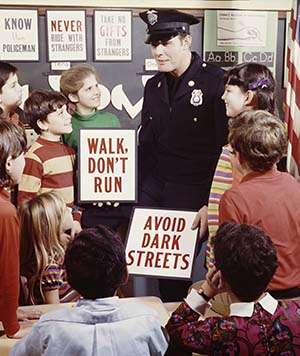

Before the 1970s there were almost zero cops in schools, and teachers would have laughed at the idea of expelling kids for the kind of behavior that routinely gets students in serious legal trouble today.

It was not the first time something like this had happened in Collingswood. Superintendent Scott Oswald confessed to reporters that administrators at his various schools were in the habit of calling the cops as frequently as five times per day. This in a district that contains only 1,875 students.

School officials had fallen into the habit of reporting virtually every infraction of school rules—even "simple name calling"—to the authorities. Parents were furious. Why were schools outsourcing student discipline to the police?

"The reality is, cops are blunt instruments," says education reform advocate and editor of Dropout Nation RiShawn Biddle. "Cops are there to arrest people. It's what they do. Putting a cop in a school means you are subjecting your students, your children, to the possibility of being arrested and all the things that come with law enforcement."

Collingswood teachers, at least, had to take the extra step of calling the cops. Such is not the case for schools, like Ryan Turk's, that already pay a designated SRO to roam the halls. Last May, in Superior, Wisconsin, a parent called Superior High School's principal to inform him that several male students were circulating nude images of her 15-year-old daughter on their cellphones. The daughter, "Kim," had sent the photo to one boy via Snapchat; this student then saved a screenshot of the photo and passed it along to his friends.

Violating another student's privacy is a more serious abridgment of school rules than taking a milk carton or mentioning brownies, and it would have made sense for administrators to discipline the people involved and teach them a lesson about respecting personal boundaries. Instead, the principal asked his SRO to handle things. The officer, Tom Johnson, began by interrogating the teens and collecting their phones. They mostly cooperated, unaware that they had committed a cardinal error when dealing with law enforcement: not lawyering up first.

In the course of his investigation, Officer Johnson also interviewed a 17-year-old male student, Austin Yabandith. Austin was Kim's boyfriend, and he was heartbroken to learn that she had sent a sext to someone else. Johnson asked Austin if Kim had sent him photos as well. Austin said yes, they had exchanged nude texts. They were sleeping together too. Kim's parents were OK with it—they had even supplied the young couple with condoms, according to Austin.

Johnson then asked Austin if he could borrow his phone.

"They said that all they were going to do was delete the photos from the phone so I blindly signed a paper allowing them to access it," Austin explained in a distraught email last September. A few weeks later, Johnson arrested Austin for sexual assault of a child, sexual exploitation, and possession of child pornography. The sexual assault charge alone carries a possible maximum sentence of 40 years.

Austin, unfortunately, was the victim of a sort of loophole in Wisconsin law. The state's age of consent is 18, meaning that both he and Kim were guilty of underage sex. But state law permits prosecutors to charge 17-year-olds as if they are adults. And while some states have "Romeo and Juliet" exceptions to sex offender laws—which essentially legalize sexual relations between teens of a similar age—Wisconsin makes no distinction between a 17-year-old keeping nude pics of his 15-year-old girlfriend and a 55-year-old stranger doing the same thing with shots of a grade schooler.

"I'm scared," Austin says. "My life could be completely ruined by this."

He wouldn't be the first. Marion County, Iowa, tried to prosecute a 14-year-old girl for taking PG-13 pictures of herself after the school caught 30 children engaging in risqué photo sharing. Public paranoia about the exaggerated dangers of teen sexting has hit moral panic levels, persuading schools that someone must do something—and who better than the police?

But that's a serious abrogation of responsibility on the part of schools. Teachers, counsellors, and principals are supposed to be the experts. It's their job to mediate disputes between kids and teach them good behavior, so that they learn from their mistakes. A student who is expelled or arrested for an error in judgment, on the other hand, might not get another chance.

"If the police intervene and have to get involved, there's a good probability that there's going to be an arrest," explains Chet Epperson, a retired Rockford, Illinois, police chief who is critical of the notion that law enforcement should handle school discipline. "We think that juveniles should be treated from a rehabilitation standpoint. Well, that sort of runs counter to having cops in schools."

Putting police in charge of high school students' sex lives also runs counter to current trends in the higher education system. Over the past five years, the Education Department has repeatedly informed university administrators that they, not the cops, are responsible for the well-being of students. In fact, according to the department's Office for Civil Rights, campuses must set up their own extralegal court systems to adjudicate sexual assault disputes. If the university becomes aware of a dispute, it must investigate the matter and discipline the perpetrator—even in some cases where the victim never filed a formal complaint—or else face a potential loss of federal funding. Nowhere in the office's guidance does it recommend outsourcing these disputes to law enforcement. The agency only suggests calling the cops if the victim wills it. As a result, sexual harassment and assault allegations involving college students are primarily handled internally by administrators ill-equipped to make appropriate determinations about due process and basic fairness.

So the government is getting it exactly backward. College students are adults, and the criminal justice system is an appropriate vehicle for dealing with them. K–12 students, on the other hand, are kids. When kids screw up, it usually makes more sense to send them to detention than to literally detain them in jail.

Making Schools Safer, But Not Saner It wasn't always this way. Before the 1970s there were almost zero cops in schools, and teachers would have laughed at the idea of expelling kids for the kind of behavior that routinely gets students in serious legal trouble today.

What changed? The violent crime rate in the U.S. rose 80 percent between 1975 and 1989. In response, school districts in California, New York, and Kentucky adopted "zero tolerance" policies mandating automatic expulsion for fighting, drug use, and gang activity. The idea was to keep violence out of schools by removing the most problematic students. Between 1973 and 2010, the national suspension rate doubled. By the 2009–2010 academic year, more than 1 in 10 American secondary school students reported being suspended at least once.

The biggest shock to the school discipline paradigm came in 1999, when two students perpetrated a mass shooting at Columbine High School in Colorado. The massacre touched off a national panic about violence in schools, even though schools continued to be comparatively safe places for young people—and even though the nationwide crime wave had already been receding for years. From 1992 to 2002, school crime actually halved. But the idea that police should play an important security role in schools became more entrenched than ever.

A principal driver is the federal Department of Justice's Community Oriented Police Services (COPS) office, created in 1994. Its COPS in Schools grants, active from 1999 through 2005, gave out $753 million to nearly 3,000 school districts and law enforcement agencies to hire school police. The office currently runs the COPS Hiring Program (CHP), which has given over $1 billion to hire and retain police officers since 2010. School resource officers feature heavily in this funding—in 2016 they were the second-most common CHP grant recipients. All told, the COPS office has helped hire more than 7,000 SROs since 1996, according to its own 2016 estimates.

In the 1996–1997 school year, fewer than 20 percent of public schools had school resource officers, according to the National Center for Education Statistics. In the most recent data, for 2014, that number has more than doubled, with police in over 43 percent of public schools, including nearly two-thirds of middle and high schools. The New York Police Department's Division of School Safety employs over 5,000 uniformed school security officers, nearly the size of the entire police forces of Boston and Baltimore combined.

Federal laws have had an impact on school discipline as well. In 1994, President Bill Clinton signed the Gun-Free Schools Act, which mandated that schools expel students for gun offenses in order to be eligible for federal funds. Since then, the law has been expanded to apply to other weapons, too. By 1997, zero tolerance policies were in vogue nationwide: 94 percent of schools had them for firearms, 87 percent for alcohol possession, and 79 percent for tobacco possession or on-campus violence.

Administrators thus lost the ability to apply discretion in cases where a stern warning might have sufficed. And prohibitions on "lookalike" weapons have become commonplace as well, leading to punishments for the silliest of infractions. Schools have suspended students for possessing nerf guns, paintball equipment, fishing gear, powder that looked like drugs but wasn't, and much else. A Massachusetts school suspended a 10-year-old boy for pretending his hand was a laser gun.

Unsurprisingly, these silly punishments infuriate parents. But unless they can afford private schooling, they have little recourse. Students must attend the public school assigned to them based on their zip code: That's how the system works. Don't like that your district expels kids for eating their pop-tarts too aggressively or arrests teens for sharing selfies? Too bad.

Right to Remain Silent? As U.S. schools filled with cops, administrators grew used to relying on police to address disciplinary issues. Having a cop on hand could be beneficial in extreme cases where a student becomes a safety threat. But Epperson, the former Rockford police chief, also wonders if the presence of a police officer could negatively impact school morale.

"It's like a cop in a bank," he says. "First thing you think when you walk in is this place may have been robbed at some point. What's the message if I see a cop in the school?"

What's more, there is little evidence this punitive approach actually reduces crime. "It's never been proven to be effective," says Biddle. On the other hand, students who are suspended or expelled are more likely to suffer problems at home, abuse drugs, and get into fights, according to the American Academy of Pediatrics. The same report found little evidence that suspension or expulsion even acts as an effective deterrent against disruptive behavior in school.

The trend of using school police, metal detectors, and surveillance systems to handle misbehavior also undermines students' constitutional rights. "To teach students in poor communities that the Constitution allows their privacy to be invaded by the police because they have writing on their backpack, or a bandanna in their pocket…is troubling," the Harvard Law Review opined in 2015. Young people get the idea that public safety is a broad and malleable pretext, and that students don't have the right to object to mistreatment. Such abuses are even more egregious when wielded against a group of people with no political power and limited legal recourse.

How well will students appreciate the freedoms enshrined in the Bill of Rights if school police officers conducting searches or interrogations routinely deny them those protections? Supreme Court Justice William J. Brennan said as much in his 1981 dissent in Doe v. Renfrow, arguing that "schools cannot expect their students to learn the lessons of good citizenship when school authorities themselves disregard the fundamental principles underpinning our constitutional freedoms."

The Supreme Court originally didn't even recognize students' Fourth Amendment rights, arguing that schools had a duty as "surrogate parents" to provide safety. This changed in 1985 after the Court established that schools needed to have "reasonable suspicion" that a student was violating laws or school rules to conduct warrantless searches. But reasonable suspicion requires a lot less to go on than the standard probable cause that applies to adults. Especially when something as innocuous as suspicion of breaking a minor, non-safety-related school rule can be used as an excuse for a search.

This can have particularly serious consequences for kids who are already working from behind. Students who act up in more subjectively defined ways, such as disrespecting a teacher or being too loud, are increasingly likely to earn court referrals where detentions once sufficed. This has caused some to wonder if we've unwittingly created a "school-to-prison pipeline." At the same time, zero tolerance laws can often remove the discretionary powers principals once had to settle disciplinary issues. Such policies normalize the experience of going to court—worrisome enough even before you get to their disproportionate application against minority students.

In the past decade, studies from Yale, Johns Hopkins, the National Education Policy Center, and others have found that students of color, students with disabilities, and LGBT students are all significantly more likely to be punished with suspension even though they typically commit offenses at similar rates as their peers. And according to the National Center for Education Statistics, schools with higher percentages of low-income kids are more likely to have police.

Schools Should Compete for Kids Changing the rules of the game requires federal, state, and local reforms. With little evidence that police in schools make students safer and plenty that they facilitate harm to students' liberty and well-being, the Department of Justice should end the cops program's SRO grants to districts. Taxpayers should not be on the hook for billions that promote unjust school conditions and put kids at greater risk of future involvement with the criminal justice system. And students should feel like they can talk to school officials when they have problems without forfeiting their constitutional rights and winding up in the back of police cars.

But in order for school staff to take their proper role in school discipline, they need discretion. Zero tolerance laws at the federal and state level need to go. Like mandatory minimums for adults, zero tolerance ordinances are heavy-handed solutions to non-existent crime waves. A principal shouldn't feel legal pressure to expel a student whose misbehavior could be dealt with less harshly.

Funding for traditional public schools is only narrowly connected to actual students and leaves the principal without much say over how resources are used. Districts often determine funding through a complex system of calculating a school's average teacher salary to determine how many staff positions it can hire. These positions are usually only based on rough enrollment quotas. On top of that, most public principals only control 5 percent of their schools' funding, because the districts give them resources in special funds they have to use for specific purposes, like reading enrichment or buying textbooks. Or hiring police officers. The result is a confusing, inefficient system that makes it hard to hold anyone accountable.

A promising alternative is student-based budgeting. Imagine putting each child's individual education dollars in his or her backpack. Wherever children choose to go to school, their "backpack funding" follows them. Beyond a baseline amount, different kids get extra funding "weights" to help them overcome additional obstacles they may face, like living in poverty, needing to learn English, or having a disability. Most principals operating under student-based budgeting also get much more control over how dollars are spent, letting them use their local knowledge to determine the best priorities for their students.

If we want to improve disciplinary outcomes, centering the money on the kids in the system, rather than the professional adults, is a good way to start. Charter schools and private schools already get money for every child they enroll and lose money for every child who leaves. When we extend that same accountability to traditional public schools, there's potential for those new incentives to change the way administrators treat kids.

A principal who is on the fence about expelling a student might handle the matter differently if he understands that there's a direct financial benefit attached to the student's enrollment in his school. Thus, student-based budgeting could raise the priority level of students' long-term welfare.

'There Are No Calls to the Police on Any Child' More than 30 districts nationwide use student-based budgeting, and more could be adopting it soon thanks to a federal pilot program in the newly passed Every Student Succeeds Act. There's not yet a lot of research on the budget formula's impact on discipline—and where zero tolerance laws constrain principals, incentives can only go so far. But where school leaders have more leeway, student-based budgeting has the potential to help our school system see more disruptive kids as customers to be worked with, not liabilities to be cast aside.

Baltimore undertook an early experiment in such budgeting, implementing its formula in 2009. In just two years, the city's juvenile crime rate took a nosedive, with juvenile shootings and arrests down 67 and 58 percent, respectively. The city's school outcomes improved as well, with suspensions and truancy decreasing by over a third, dropouts plummeting by 56 percent, and graduation rates even improving by 12 percent. Juvenile arrests, unfortunately, have started to tick back up in the last two years—a reminder that reforms can only do so much while zero tolerance policies remain in place.

Like traditional public schools under student-based budgeting, charter and private schools only get money for students that enroll. Some critics point to anecdotal cases of high suspension rates in some charter networks. These concerns aren't unfounded, but they ignore the wide array of school environments that charters make possible thanks to the increased flexibility they enjoy. And several cities with large charter sectors have already implemented reforms to mitigate potential discipline abuses.

Like mandatory minimums for adults, zero tolerance ordinances are heavy-handed solutions to non-existent crime waves. A principal shouldn't feel legal pressure to expel a student whose misbehavior could be dealt with less harshly.

Washington, D.C., uses student-based budgeting to fund its traditional public schools and enrolls over 44 percent of its students in charter schools. To help address disciplinary concerns, the district compiles "equity reports" for both kinds of schools. The reports list suspension and expulsion rates as well as test scores and enrollment over the year, breaking the data down by race, income, English language proficiency, and special education. The reports compare individual schools' data with city averages and are available online, providing parents and school leaders with a valuable source of transparency and accountability not available in most districts. Since the city began compiling the reports in 2012, suspension rates have consistently declined—both in general, and for black, special needs, and low-income students.

New Orleans is another city known for public school choice. In the wake of Hurricane Katrina's destruction, the almost-all-charter Recovery School District emerged. New Orleans has citywide open enrollment, giving students the power to attend anywhere there is space. With its students free to choose from a huge variety of charter schools experimenting in a huge variety of educational models, test scores skyrocketed over the course of a decade.

Less well-known is that New Orleans adopted new expulsion standards in 2012 and 2013 to respond to concerns over excessive discipline. The standards create a three-tiered list of offenses that can get a student referred for an expulsion hearing. Often, the hearings end up facilitating the student and school to work out a plan to address future behavioral issues.

To proceed, schools typically have to show that preventive actions were tried and that a student's behavior wasn't due to a disability. If the student is still expelled, there are several options depending on the offense, including transferring to a different school in the district, enrolling in an alternative school, entering homeschooling with resources for the parents, or sometimes returning to the original school under probation.

New Orleans' expulsions have nearly halved since these reforms were enacted, and a survey of educational and community leaders from the Center for Reinventing Public Education found widespread support for the new system among school leaders, community activists, and school board members, thanks to its speedier processing, greater transparency, and increased consistency.

These cities' approaches are different, but there is a common thread. Both D.C. and New Orleans let school funding follow kids to wherever they attend, and both offer lots of options for those kids to choose from. These conditions then encouraged constructive school discipline reforms.

Of course, not everyone prefers a more gentle approach. Some parents opt to send their children to private or charter schools with sterner disciplinary environments, so long as the discipline is kept within the school. Bolanle Akinola is a Nigerian immigrant and mother of two kids enrolled in the D.C. Opportunity Scholarship Program, a voucher program for low-income children. Akinola's gratitude for the program's existence is palpable. Before the program allowed her 9-year-old daughter to transfer to the private Calvary Christian Academy, the girl was regularly being bullied.

"They beat her," Akinola says of the students at her daughter's old school. As for the administration? "They don't do anything about it."

At Calvary, Akinola's daughter enjoys going to school. She is also comfortable talking to her teachers when she has a problem, because she's not afraid of disproportionately dire consequences—for herself or her fellow students. She trusts school authorities to be strict with other kids, without crossing the line into police intervention.

"There are no calls to the police on any child," says Akinola. "It's just a family. They teach them well."

More choices mean parents like Akinola can take their kids elsewhere if the schools assigned to their zip codes aren't fitting the children's needs, academic or disciplinary. And schools like Calvary have the financial incentive too many public schools lack to create a more positive learning experience.

Many families across the country don't have these choices. They're assigned a traditional public school based solely on where they live, and they can't afford to move to a different neighborhood or to pay for a private school if their children are victims of overzealous school police or administrators.

Everyone deserves access to a wider variety of options. Clapping students in handcuffs isn't the right approach to school discipline, and it certainly shouldn't be the only one.

This article originally appeared in print under the headline "Why Are Cops Putting Kids in Cuffs?."

Show Comments (68)