After Banning Kratom, DEA Says It Might Be a Useful Medicine

"Our goal is to make sure this is available," a spokesman says.

Officials at the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) seem to have been surprised by the negative reaction to the agency's "temporary" ban on kratom, which it implausibly claimed was necessary "to avoid an imminent hazard to public safety." That ban, which will last at least two years, can be extended for another year, and during that time the DEA is supposed to go through the motions of justifying the decision it has already made. But according to DEA spokesman Melvin Patterson, the agency may decide not to keep kratom in Schedule I, the most restrictive category under the Controlled Substances Act (CSA).

"I don't see it being Schedule II [or higher] because that would be a drug that's highly addictive," Patterson tells Washington Post drug policy blogger Christopher Ingraham. "Kratom's at a point where it needs to be recognized as medicine. I think that we are going to find out that probably it does [qualify as a medicine]."

Patterson makes it sound as if the DEA had no idea Americans were using kratom for medical purposes, even though it discusses those uses in its explanation of the ban. The storm of protest from medical users of kratom, which included a demonstration near the White House on Tuesday, "was eye-opening for me personally," Patterson says. "I want the kratom community to know that the DEA does hear them. Our goal is to make sure this is available to all of them." And what better way to do that than banning all kratom products?

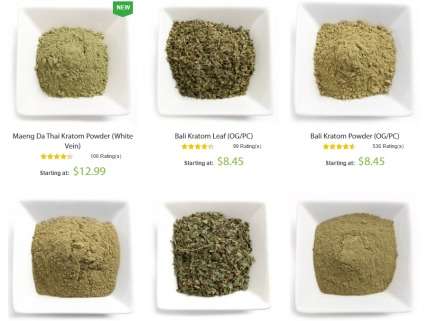

Patterson's comments are surprising, not least because they contradict conclusions the DEA already has reached about kratom, a pain-relieving leaf from Southeast Asia that recently gained a following in the United States as a home remedy and recreational intoxicant. Explaining why it decided to ban kratom, the DEA says "available information indicates that [mitragynine and 7-hydroxymitragynine, kratom's main active ingredients] have a high potential for abuse, no currently accepted medical use in treatment in the United States, and a lack of accepted safety for use under medical supervision." Those are the criteria for Schedule I, which Patterson now says is not appropriate for kratom.

Although the DEA does not have to demonstrate that kratom meets the criteria for Schedule I to put it there temporarily, it goes to great lengths to show that kratom has "a high potential for abuse," mainly by classifying everything people do with it as abuse. Under the CSA, drugs in the top two schedules are all supposed to have a "high potential for abuse," while drugs in lower schedules (III through V) are supposed to have progressively less abuse potential. Patterson suggests a drug cannot have a high potential for abuse unless it is "highly addictive," which kratom is not. Yet neither are many other substances in Schedule I, including marijuana, qat, LSD, psilocybin, mescaline, MDMA, and dimethyltryptamine, assuming addictiveness is measured by the percentage of people who become heavy users after trying a drug. Evidently a drug need not be highly addictive to be placed in Schedule I.

Nor does the DEA define abuse potential based on the hazards a drug poses. Chuck Rosenberg, the agency's acting administrator, notes that "Schedule I includes some substances that are exceptionally dangerous and some that are less dangerous (including marijuana, which is less dangerous than some substances in other schedules)." Emphasis mine, because people tend to assume that Schedule I is a list of what the DEA considers to be the world's most dangerous drugs. The DEA does not see it that way. "It is best not to think of drug scheduling as an escalating 'danger' scale," Rosenberg says.

If "high potential for abuse" does not refer to addictiveness or to danger, what does it signify? Nothing more than the DEA's (or Congress's) arbitrary preferences. "High potential for abuse" is a political concept, not a medical or scientific assessment. If the DEA (or Congress) does not like a particular kind of drug use, that use is abuse by definition. Since the DEA does not recognize any legitimate medical or recreational use for marijuana, LSD, or kratom, the abuse potential of these drugs is demonstrated by the fact that humans consume them.

In addition to applying a highly elastic definition of drug abuse, the DEA says a controlled substance must be placed in Schedule I, regardless of its abuse potential, unless it has "a currently accepted medical use." So even though marijuana is less dangerous and less addictive than drugs in lower schedules, it has to stay in Schedule I until the DEA decides there is enough evidence to demonstrate its medical utility. Likewise with kratom.

Although Patterson, the DEA spokesman, says "kratom's at a point where it needs to be recognized as medicine," the DEA says otherwise. It notes that the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has not approved kratom as a treatment for any medical condition. Nor is the FDA considering any applications to approve kratom as a medicine. "Kratom does not have an approved medical use in the United States and has not been studied as a treatment agent in the United States," the DEA says. As far as the DEA is concerned, that means kratom cannot possibly have a currently accepted medical use.

So how does Patterson imagine that kratom will be "recognized as medicine"? Ingraham says Patterson "cautioned that research would be necessary to know for sure how to best regulate the drug." The DEA says no such research has been conducted yet, and medical studies will be much harder to do now that kratom is a Schedule I drug. To recognize a medical use as "accepted," the DEA wants to see the sort of large, expensive clinical trials that the FDA requires before approving a new pharmaceutical. It hardly seems likely that such research will be completed during the next two or three years, starting from zero, in the forbidding regulatory environment that the DEA has just created.

Show Comments (49)