How the "Black Silent Majority" Kicked the Drug War into High Gear

Harlem activists called for federal troops to "clean up" the streets, demanded life sentences for drug dealers.

There was a spiritual predecessor to the Nixonian "silent majority," the white middle-class who weren't particulary political by nature, but who quietly supported crackdowns on crime in the wake of the social upheaval of the 1960s. They helped launch the War on Drugs and by extension, the era of mass incarceration and increasingly militarized police which continues to this day.

And they were black.

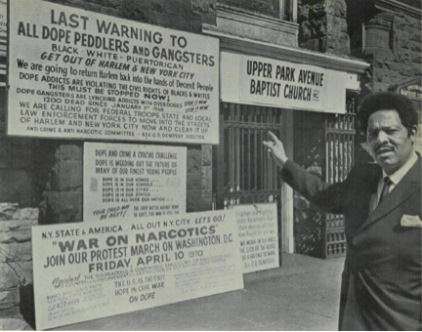

In his new book, "Black Silent Majority: The Rockefeller Drug Laws and the Politics of Punishment," Michael Fortner lays out the efforts of community activists, mostly centered in Harlem and other parts of New York City in the 1950s and 1960s, who used rhetoric so violent it would make Donald Trump blush (e.g. "Take the junkies off the streets and put them in camps," "Kill the pushers," "We (call) for federal troops, state and law enforcement forces to move into the streets of Harlem and New York City now and clean it up").

Fortner's book is profiled by Jesse Singal in New York magazine, where residents of Harlem are said to have endured "a heightened sense of anger, fear, and despair greatly attenuated the appeal of the so-called "old penology" favored by white liberals (as well as a lingering minority of black voices), which emphasized treatment and rehabilitation over punishment" during a "a devastating, drug-fueled increase in crime in the 1960s that peaked around 1971 — one that included countless grisly murders, muggings, and burglaries."

Seeking respite, these advocates pushed for increased punitive reactions to drug-related crime. They found their greatest ally in New York's liberal Republican (remember those?) Governor Nelson Rockefeller, who's ambitions for national office and an electorate clambering for "law and order," pushed him to support a series of laws that would become notorious while bearing his name:

Passed in 1973, they imposed harsh penalties on those convicted of drug-related offenses, including mandatory life sentences for the sale of many hard drugs and harsh sentences for possessions of small quantities. Between their enactment and 2009 repeal, they were responsible for a massive wave of incarceration over minor drug convictions — one that disproportionately targeted black and Latino New Yorkers.

Even after the laws were passed, "71 percent of black respondents [in New York City] favored life sentences without parole for pushers." Though they were repealed in 2009, in great part because of the efforts of black activists, Fortner bristles at the prevailing wisdom which paints the laws' passage as strictly a black-white issue, which he says "robs African-Americans of their agency."

It's an important point. Laws passed as emotional reactions to societal ills frequently backfire (see: anti-pedophilia laws which inadvertently turn teenage lovers into lifelong sex offenders), but rewriting history to conform with a politically convenient narrative that the Rockefeller Laws were the result of purely racist and discriminatory motivations inhibits present-day conversations about how sweeping policies can ultimately exacerbate the problem they were designed to alleviate.

Show Comments (97)