The 'Moral, Libertarian Premises' of the U.S. Constitution

In my recent book Overruled, I examine one of the central questions in American law. How much deference does the Supreme Court, an unelected body, owe to legislation that has been duly enacted by democratically accountable lawmakers? For example, when the people, acting through their elected representatives, decide to outlaw a certain form of activity (such as forbidding the sale or possession of birth control devices), what gives the Supreme Court the authority to override their wishes? Why should nine unelected judges get to trump the legislative will of the majority?

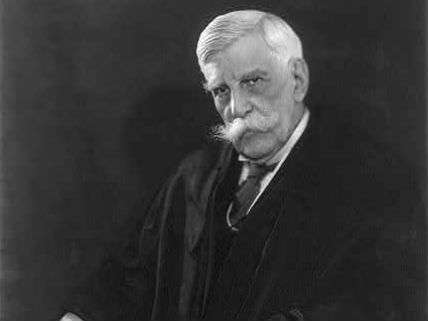

The answer, according to Progressive era Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr., perhaps the famous advocate of judicial deference in American history, is that the Supreme Court should not trump the wishes of such a majority. Instead, the Court should basically let the majority rule as it sees fit. "A law should be called good if it reflects the will of the dominant forces of the community," Holmes maintained, "even if it will take us to hell."

In recent months, I've debated this question with an assortment of liberal and conservative legal pundits, all of whom favored some version of Holmes-style judicial deference. For my part, I've argued that the Constitution is a liberty document which protects a broad range of individual rights (and also places strict limits on government power), and it is both necessary and proper for the judiciary to protect those rights (and enforce those limits) against government overreach—even when that means that the Supreme Court ends up acting in an anti-majoritarian, or indeed anti-democratic manner.

The debate, however, is far from settled. A welcome new entry in it comes from Amherst College professor Hadley Arkes, the author of a splendid 1994 biography of Supreme Court Justice George Sutherland, a famous judicial foe of the New Deal. Writing today at the Library of Law & Liberty, Arkes weighs in with a long, thoughtful take on the proper role of the courts. It is well worth reading in its entirety. Here is a taste.

"Quite recently," Arkes observes,

some conservative writers, deeply concerned about 'judicial supremacy' or a judicial 'activism' run amok, have sought to find the remedy in a state of affairs that would invert [the Constitution's] moral, libertarian premises. These conservatives would set the presumption in favor of the validity of those laws enacted by people who were elected as legislators, and who remain responsible to the voters who elected them. That 'remedy' would remove, in a stroke, the presumption of liberty and the burden of moral reasoning that should be borne by legislators as they seek to override that personal freedom on any matter.

Arkes advocates a different approach. "A government committed to the protection of natural rights is a government that bears the burden of justification for its acts," he maintains. What does he mean by that?

In the classic understanding, we do a portentous thing when we impose laws on other people, and that move will always call for a justification, an explanation of what makes it just or rightful for others as well as ourselves. Those creatures we call "moral agents" have a presumptive claim to all dimensions of their freedom, and the burden lies with the law in supplying a moral justification for overriding that freedom.

When liberty is connected in this way to its moral ground, we find that the law would begin on terms that are quite at odds with what we've been hearing of late even from conservative commentators in the law. For the law would begin with this premise: that ordinary human beings have a presumptive claim to all dimensions of their freedom, and not merely to the liberties that were set down in the first eight amendments to the Constitution.

Today's libertarian legal movement favors something very much like this approach. As I noted back in January:

the libertarian legal movement views the Constitution as a liberty document which protects a broad range of individual rights against arbitrary and unnecessary government infringement. What counts as arbitrary and unnecessary government infringement? In the context of economic regulation by state and local governments, the answer depends on whether the law in question serves a legitimate and verifiable public health or safety purpose. If the regulation fails to serve such a purpose, then the courts should strike it down for violating the economic liberty protected by the 14th Amendment. If the law serves such a purpose, it gets to remain on the books.

In short, the courts are there to police the other branches of government, to insure, as Arkes puts it, that the government "bears the burden of justification for its acts."

For more on the longstanding debate over judicial deference, check out my book.

Show Comments (71)