If Freddie Gray's Knife Was Legal, Does That Mean His Arrest Wasn't?

Did police reasonably think he was carrying a switchblade?

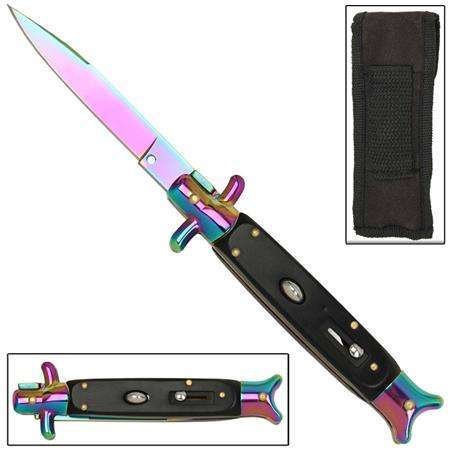

Last week a lawyer for Edward Nero, one of the Baltimore cops charged in connection with Freddie Gray's death as a result of injuries he suffered in police custody, requested access to the knife that was the basis for Gray's arrest. Gray was charged with violating Baltimore's ban on switchblades, but Marilyn Mosby, the local state's attorney, says his knife was legal. She has charged Nero and two other officers with false imprisonment for arresting Gray without probable cause to believe he had committed a crime. Nero insists the arrest was justified and wants a chance to prove it by examining the knife.

Who is right? Maybe both. Based on the way the knife has been described, it did not qualify as a switchblade. At the same time, confusion on that point undermines Mosby's argument that Nero and his colleagues knew or should have known Gray's arrest was not justified.

Baltimore's ordinance defines a switchblade as "any knife with an automatic spring or other device for opening and/or closing the blade, commonly known as a switch-blade knife." By contrast, police described Gray's knife as "a spring-assisted, one-hand-operated knife." Knife Rights Chairman Doug Ritter and Evan Nappen, a Second Amendment attorney and the author of an upcoming book on knife laws, note that the switchblade ban was passed in 1950, while "spring-assisted knives (also called 'assisted-opening' knives) were not invented until the 1990s." There is a clear functional difference between these two kinds of knives: Switchblades have a "bias toward opening," so that releasing a latch by pressing a button or flicking a lever in the handle causes the knife to spring open. Spring-assisted knives have a "bias toward closure," meaning you initially have to manually move the blade by pushing against a hole or stud. "In a typical spring-assisted knife," Ritter and Nappen write, "the blade must be moved 20-30 degrees open before the spring takes over to finish opening the blade."

Baltimore's ordinance refers to "an automatic spring or other device for opening and/or closing the blade," which in context means a device that allows the knife to open automatically, especially since the ban applies only to knives that are "commonly known" as switchblades. "Spring-assisted knives are not switchblades," Ritter and Nappen say. "They have never been 'commonly known' as switchblades, especially in 1950, which was over 40 years before spring-assisted knives were even invented." And if police really thought Gray's knife was a switchblade, why didn't they call it that?

Even if Gray's knife was legal, that does not necessarily mean his arrest wasn't. That depends on whether Nero's reading of the law, which according to The Baltimore Sun was backed by the police task force that investigated Gray's death, was reasonable. A reasonable, though incorrect, belief that Gray had broken the law would have given police probable cause for an arrest. The disagreement about what the law bans therefore could be enough to create reasonable doubt as to whether the officers are guilty of false imprisonment.

At the same time, the argument about what counts as a switchblade in Baltimore discredits the law that Nero et al. claim they were enforcing. Due process requires laws clear enough so that you know when you are breaking them. If it is uncertain whether spring-assisted knives are illegal in Baltimore, it cannot be fair to punish people for possessing them, regardless of your views on knife control generally. As I said last week, vague laws like this one invite abuse, handing police yet another excuse for harassing people who have committed no real crime.

Addendum: Fox News notes an excellent 2014 Village Voice story in which Jon Campbell explains how a 1954 ban on "gravity knives" led to thousands of arrests a year in New York City, frequently involving people who used the tools for work or other innocent purposes and had no idea they could be deemed illegal. State law defines a gravity knife—a sort of springless variation on the switchblade—based on a "wrist flick" test: Can the knife be opened with one hand by flicking your wrist? It turned out that was possible, though often difficult, with many folding knives sold openly throughout the city. Yet people who bought these knives at hardware or sporting goods stores could be arrested for possessing them as soon as they ventured outside—a risk that was especially high for black and Hispanic men.

A bill that would narrow New York's gravity knife ban to avoid ensnaring innocent people died in the state legislature last year but was reintroduced this year in the Assembly and Senate. It says "possession of a gravity knife shall constitute criminal possession of a weapon in the fourth degree only if the defendant has intent to use the same unlawfully against another."

[Thanks to Marc Sandhaus for the Fox News link.]

Show Comments (137)