SCOTUS Seems Inclined to Reject Censorship of Confederate Flag License Plate

If specialty plates are government speech, Texas officially loves golf and hates abortion.

In a case it heard yesterday, the Supreme Court considered whether messages on specialty license plates constitute private speech and, if so, what kinds of restrictions might be consistent with the First Amendment. The case involves a Sons of Confederate Veterans plate that the Texas Department of Motor Vehicles rejected in 2011 on the grounds that many people would be offended by the Confederate flag it featured. Explaining its decision, the DMV board said "a significant portion of the public associate the Confederate flag with organizations advocating expressions of hate directed toward people or groups that is [sic] demeaning to those people or groups." Last year the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 5th Circuit said that was not a constitutional reason for censoring speech in this context, and yesterday several justices seemed to agree.

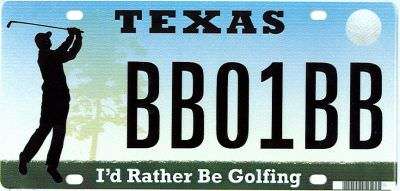

Although five of the six circuit courts to address this issue have held that specialty plates constitute private speech, Texas argues that all 438 of the messages it has approved—ranging from "Don't Tread on Me" and "Choose Life" to "Rather Be Golfing" and "Mighty Fine Burgers"—actually represent government speech, which means the First Amendment does not apply. "Messages on Texas license plates are government speech," Texas Solicitor General Scott A. Keller told the Court. "The First Amendment does not mean that a motorist can compel any government to place its imprimatur on the Confederate battle flag."

Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg seemed unpersuaded. "Is it government speech to say 'Mighty Fine Burgers' to advertise a product?" she wondered. Justice Anthony Kennedy also sounded skeptical:

Is this a case where the state, the government, has aided in creating a new kind of public forum? People don't go to parks anymore. If the government bought soapboxes to put around the park, that's government property, but the government can't prohibit what kind of speech goes on there. Why isn't this a new public forum?

Similarly, Justice Samuel Alito compared specialty license plates to government-owned billboards and wondered if the state would have carte blanche to suppress certain viewpoints in that context as well. The park and billboard analogies apparently appealed to Justice Sonia Sotomayor, who said Keller had not adequately addressed them.

Justice Elena Kagan also seemed inclined to view the plates as a kind of public forum, saying, "In a world in which you have approved 400 license plates and they are pretty common in the State of Texas and you have only disapproved a very select few…it does seem as though you've basically relinquished your control over this and…made it a people's license plate for whatever…people want to say."

Chief Justice John Roberts did not seem to be buying the government-speech argument either:

I'm not quite sure why it's government speech since there's no clear, identifiable policy—at least, it's arguable there's none—that the state is articulating. I mean, they're only doing this to get the money.

Even Justice Stephen Breyer, perhaps the most pro-government member of the Court, was practically begging Keller to articulate an acceptable rationale for rejecting some plates while accepting others. "I just think you have to have some kind of legitimate reason," Breyer said. "It doesn't have to be much. It could be just a little." Of the eight justices who spoke (Clarence Thomas was silent, as usual), only Antonin Scalia seemed inclined to accept the state's argument.

Still, at least a few justices were troubled by the implications of preventing Texas from discriminating among viewpoints on license plates. Keller raised the prospect of license plates supporting "Al Qaeda or the Nazi Party," and R. James George Jr., the lawyer representing the Sons of Confederate Veterans, agreed that the state would have to allow license plates featuring swastikas, racial slurs, the word jihad, and political slogans such as "Make Pot Legal." Ginsburg wondered, "Is the choice between everything or nothing?" If so, Scalia said, George was "really arguing for the abolition [of] Texas specialty plates," since the state would prefer that outcome to allowing messages it deems offensive.

Roberts seemed untroubled by the prospect. "If you don't want to have the Al Qaeda license plate," he said, "don't get into the business of allowing people to buy the space to put on [a plate] whatever they want to say."

Show Comments (49)