Why Police Officers Keep Claiming Their Unarmed Victims Had Guns, and What We Can Do About It

Police officers keep claiming that they genuinely thought their unarmed victims had lethal weapons. Ferguson police officer Darren Wilson, who shot unarmed black teenager Michael Brown, claims in his grand jury testimony that Brown put his right hand "under his shirt in his waistband" and then lunged at him—153 feet away. Yet Michael Brown did not have a gun. Instead he was shot 7 times, with the last shot being lethal.

Just last Monday, Ohio police officers shot Tamir Rice, a twelve-year old African-American child, because they thought his fake "airsoft"-type pellet gun was an actual gun. In August, Ohio police officers gunned down an unarmed African-American customer in a Wal-mart talking on his cell phone who had picked up a pellet gun, out of its package, that was sitting on the shelf. The special prosecutor, who argued the case in front of a grand jury who did not indict any police officer, tried to explain at a later press conference:

"The law says police officers are judged by what is in their mind at the time…You have to put yourself in their shoes at that time with the information they had."

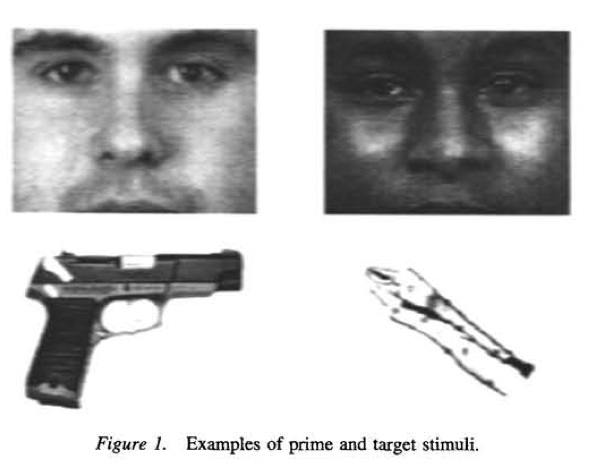

Academic research, however, tells us that more than a police officer's conscious intentions may influence their judgments and actions. University of North Carolina psychologist Keith Payne (2001) conducted an experiment finding research participants were more likely to mis-identify a hand tool as a gun when they had to respond quickly, immediately after being shown the face of an African-American male rather than a Caucasian male. Particularly, white and male respondents were faster to identify guns when "primed" with a black face versus a white face.

This suggests that police officers like Daren Wilson may have genuinely believed their lives were threatened, and acted accordingly—but that their conclusions were unduly and implicitly influenced by their own stereotypes.

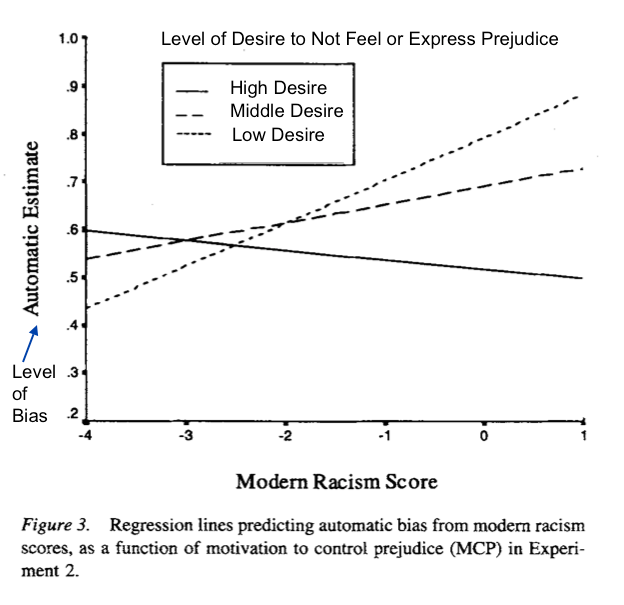

But there is hope. Payne also found that an individual's personal desire to overcome prejudice—to not feel it or express it—moderated the effect of racial bias on categorizing tools or guns. For instance, those who were more likely to agree with statements like, "I get angry with myself when I have a thought or feeling that might be considered prejudiced," or "It's never acceptable to express one's prejudices" were significantly less likely to implicitly allow their own stereotypes to influence their performance in the experiment.

This chart is probably one of the most hopeful findings of social science research: we as individuals can make choices that reduce the effect of prejudices or stereotypes we may hold. The horizontal axis of the chart measures an individual's implicit racial prejudices and the vertical axis essentially measures the effect of racial bias exhibited during the experiment. The three plotted lines represent different levels of desire to suppress one's prejudices. The solid black line shows that among those who had high desire to overcome their prejudice, their implicit racial stereotypes did not affect their experiment performance. However, the small dotted line shows that for those who cared little about their own prejudice, their racial stereotypes significantly and substantially affected their behavior in the experiment.

This chart quickly summed up is this: One's personal desire to overcome prejudice can significantly and meaningfully moderate the effect of subconscious stereotypes and the (perhaps unintended) harms they may cause.

This has implications for society generally and also law enforcement specifically. Police officers are often in situations where they must make quick judgments in a stressful environment. Payne's research suggests that even police officers intending to be fair may allow their subconscious stereotypes to influence their judgments unless they make a concerted effort to care about overcoming such prejudices.

(Charts from B. Keith Payne. (2001). Prejudice and perception: The role of automatic and controlled processes in misperceiving a weapon. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 81(2), 181-192. Figure 3 legend and vertical axis label revised for reader clarity.)

Show Comments (86)