Are Police More Damned Trouble Than They're Worth?

Modern police forces have become little more than a new set of predators from which the public needs protection.

In the spring, months before Michael Brown was shot and Ferguson erupted in reaction, whoever writes New York City Police Commissioner William J. Bratton's blog for him posted, "In my long police career I have often drawn inspiration from a great hero of mine, Sir Robert Peel. Peel founded the London Metropolitan Police in 1829." The post listed the nine "Peelian Principles" attributed (probably spuriously) to the founder of modern policing and formulated to combat crime in a rapidly modernizing city. The principles are remarkable both for the high ideals to which they aspire, and the minimal resemblance they bear to the actual forces over which Bratton and his counterparts around the United States actually preside.

Given the grim reality of law enforcement in today's America, it's hard to believe anything like those ideals could ever be met.

The background to the principles is no mystery. Peel and friends wanted to consolidate London's constables, night watchmen, and police forces in the growing city. But "people were suspicious of a large force, possibly armed," the U.K.'s National Archives note. "They feared it could be used to suppress protest and support military dictatorship." People feared this because the army had been used to do exactly that. In addition to the guiding principles, the police were given blue uniforms to distinguish them from military red. They originally weren't even allowed to vote to minimize their influence over government policies.

Interestingly, Bratton's version of the first principle reads, "The basic mission for which the police exist is to prevent crime and disorder." But the original version says, "To prevent crime and disorder, as an alternative to their repression by military force and severity of legal punishment." Maybe New York City's police commissioner drew from an altered-by-repetition version of the principles. Or maybe he just had difficulty seeing modern armored vehicle-riding, assault rifle-toting, police as an alternative to military force.

The principles also specify that police "use physical force only when the exercise of persuasion, advice and warning is found to be insufficient." That doesn't mean cops have to be pacifists. But it's hard to reconcile a preference for persuasion with the over-the-top police occupation of Ferguson, or the promiscuous use of militarized SWAT teams to kick in doors as a matter of routine. Only 7 percent of SWAT uses compiled by the American Civil Liberties Union involved a "hostage, barricade, or active shooter"—79 percent were to serve search warrants.

It's also hard to reconcile a dedication to the "minimum degree of physical force" with the warning to the public in the pages of the Washington Post, penned by Officer Sunil Dutta of the Los Angeles Police Department, that "If you don't want to get shot…just do what I tell you." Dutta and his colleagues apparently don't agree that "to secure and maintain the respect and approval of the public means also the securing of the willing co-operation of the public," as the principles would have it.

For that matter, willing cooperation requires that the public knows what the police are up to in order to have any sort of opinion on the matter, willing or otherwise. So when police forces actively conceal the use of techniques and technology, such as cellphone-tracking stingray devices, from public scrutiny and judicial oversight, cooperation isn't even being sought.

And when that concealment is not an isolated incident, but involves departments from coast to coast deceiving the public on the advice of the federal government, it's obvious that, at least in this country, Sir Robert Peel's heirs have lost any interest in the idea that they are "only members of the public who are paid to give full time attention to duties which are incumbent on every citizen."

Modern saturation policing—when cops swarm a neighborhood or randomly throw roadblocks over major roadways—is openly intended as a form of intimidation. The Tennessee Highway Patrol plans "driver's license, sobriety and seatbelt checkpoints, as well as saturation patrols and bar and tavern checks" over Labor Day weekend to scare the public into compliance with a laundry list of rules and regulations. It's probably more effective at making people afraid to leave the house on a holiday lest they trip over lurking troopers. It's also at odds with the idea that "the test of police efficiency is the absence of crime and disorder, and not the visible evidence of police action."

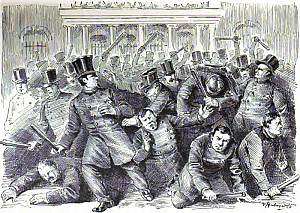

It's not that there was ever a golden age of policing. Within a few years of the Metropolitan Police Department's creation, peelers were sent after Chartist political demonstrators (though they did avoid the sabers-swinging tactics that the military brought to such occasions with bloody enthusiasm). Police officers were frequently drunk and corrupt.

It's also unclear that the new police actually reduced crime, with criminal court proceedings continuing at the same pace before and after the creation of the force.

When the idea of professional policing crossed the Atlantic Ocean, the force Bratton now leads trumped the British example. It managed not just corruption, but an actual riot between two rival departments in 1857. Fifty-three officers were injured before the state militia intervened.

But, all that said, there's a reason for the creation of such institutions as constables, night watchmen, thief-takers, police, and other efforts at keeping the peace. People don't want their property stolen, their persons abused, or their lives taken; they want to deter and punish the predators among us, and they don't always feel up to doing the jobs themselves.

But modern police forces have gone dangerously off-track. They've become little more than a new set of predators from which the public needs protection. That Dutta's column was actually a response to public outrage over police conduct shows how disconnected policing has become from the people it supposedly serves.

Bill Bratton was on to something when his blogger invoked the Peelian Principles. Those nine points, intended to appease a justifiably skeptical audience, were never perfect, and they've always been implemented by flawed human beings. But the ideals to which they aspire are a hell of a lot better than what we have now.

Show Comments (130)