What Does Denver Have Against Getting Stoned and Listening to Music?

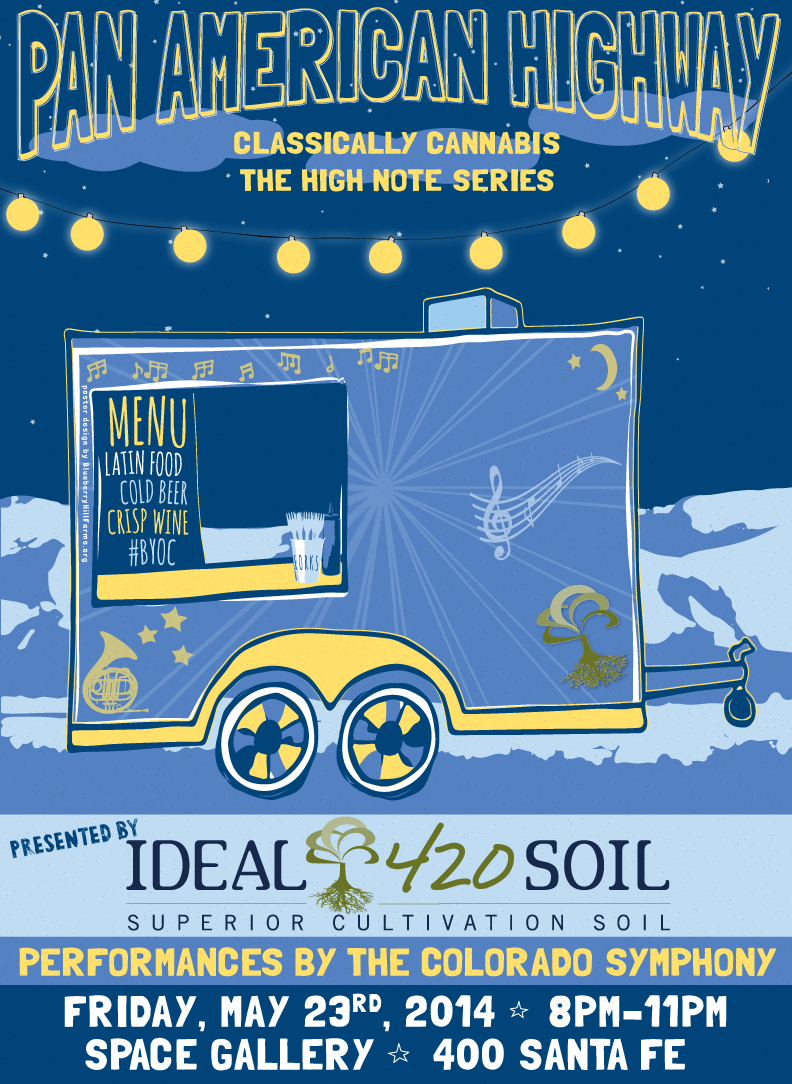

Two weeks ago, the Colorado Symphony Orchestra (CSO) announced a series of pot-friendly concerts to be held at Space Gallery, a private event venue on Santa Fe Drive in Denver. Last week Denver officials threatened to withhold permits for the concerts, saying that letting ticket holders bring their own legally acquired pot and smoke it on Space Gallery's enclosed patio would violate a 2013 ordinance that prohibits consuming marijuana "openly and publicly." Yesterday the CSO said it had reached a deal with the city that allows the "Classically Cannabis" concerts to proceed as invitation-only fundraisers. What gives?

The Denver ordinance defines openly as "occurring or existing in a manner that is unconcealed, undisguised, or obvious." It defines publicly as "occurring or existing in a public place," which it defines as "a place to which the public or a substantial number of the public have access." The CSO's lawyers obviously though that Space Gallery, which the symphony is renting for concerts that would have been open only to people who made reservations and paid for tickets, did not count as a "public place." The city disagreed, insisting on an added layer of exclusivity: Instead of letting anyone with $75 and a phone get in, the CSO will be admitting only "a closed list of VIP guests," an approach that seems to conflict with the financially troubled orchestra's goal of reaching out to a newer, younger, less stodgy audience.

Critics of Denver's pot restrictions were hoping that the CSO would challenge the city's position in court, where it would have a good chance of prevailing. As University of Denver law professor Sam Kamin told The Denver Post about the orchestra's original plan, "that sure looks more private than public." Amendment 64, which legalized marijuana in Colorado, says "nothing in this section shall permit consumption that is conducted openly and publicly." But it does not define "openly and publicly," so ultimately the courts will have to decide what that means.

Rob Corry, a Denver attorney and marijuana activist who has experimented with floating pot parties that charge admission to people who bring their own marijuana, argues that the phrase "openly and publicly" imposes two distinct conditions: To be prohibited, marijuana use must be open (visible to passers-by) and public (occurring on public property). Smoking pot while walking down a crowded sidewalk would be the paradigmatic example. But according to Corry's reading of the law, smoking pot in a secluded area of a park would be public without being open, while smoking pot on your front porch or on the patio of a restaurant would be open without being public. Smoking pot on an enclosed patio at a private venue like Space Gallery would be neither open nor public.

Although Amendment 64 declared that "marijuana should be regulated in a manner similar to alcohol," the lack of places outside the home where people can consume cannabis is a striking departure from the alcohol model. You are not allowed to consume marijuana in the state-licensed stores that sell it, and under Denver's reading of Amendment 64 you are not allowed to take it to a bar or restaurant and consume it there either, since those businesses are open to the public. "We're still trying to protect the image of our city," Councilman Albus Brooks tells the Los Angeles Times. "We will not be the capital [of marijuana], nor do we want to be. We think we led the world in responsible regulation and enforcement, and more municipalities will be joining us soon."

But if the CSO's invitation-only model is acceptable, what about cannabis clubs that are open only to members? That approach not only keeps consumption private; it allows indoor pot smoking, which the Colorado Clean Indoor Air Act prohibits in bars and restaurants (although the law allows smoking in outdoor seating, and it does not mention vaporization or edibles). A cannabis club called Studio A64 is already operating in Colorado Springs, where the city council recently gave its blessing after opponents tried to close it down. Another club is scheduled to open soon in Nederland, where local officials likewise have assented. If Colorado Springs, where the sale of recreational marijuana is banned, can nevetheless tolerate its consumption in settings other than private residences, surely Denver, which has more pot shops than the rest of the state combined, can loosen up a little.

[Thanks to Marc Sandhaus for the L.A. Times link.]

Show Comments (9)