Atlas Shrugged Part III: Who is John Galt?

The novel that praises the sanctity of money becomes a movie that's a labor of love over budgets.

John Aglialoro is a businessman, and a very successful one, named by Fortune magazine in 2007 as the 10th richest small business executive in the country. But his latest project is, he says, about "love."

It's the film Atlas Shrugged III: Who is John Galt?, the conclusion of a trilogy of movies based on Ayn Rand's massively successful and influential 1957 novel about a world driven to the brink of collapse by statism in the supposed service of altruism.

"Someday I just want to go visit [Ayn Rand's grave] and say 'I got it done.' What a magnificent mind, what a great contribution," he says about the author whose works jolted him and helped him understand the world.

I questioned the business sense of Aglialoro's foray into filmmaking during a February interview on the set of Atlas III. The first two movies in the trilogy were financial failures, losing him millions.

"We don't know that the trilogy will not make money," he corrects me. "We know Part I did not and Part II did not." The combined production costs for all three will come to about $20 million, he says. "But I believe with this third piece—it's like a symphony. The adagio, what do you get out of it? It's boring to many people. They want the crescendo."

He is confident they still have a lot to fans of the novel to reach. He and his production partner Harmon Kaslow both say that to this day they find people heavily into Rand who still don't know this three-part film project is even happening. "We discovered of the population of people who read the book, we really haven't reached a substantial percentage of those people," says Kaslow. He praises their associate producer and online promotion maven Scott DeSapio for building an Internet community of donors and honorary producers who will hopefully be their best advertisers.

They've been as open to fans as perhaps any movie in production has ever been, creating a "Galt's Gulch Online" for supporters, inviting dozens of them to visit the set, and frequently broadcasting live video from set during the shoot. DeSapio notes the novel has sold hugely and steadily for decades, "and you know how high the advertising budget is for that? Zero. It sells because people talk to people [about the book] and if we can make an Atlas that a [fan of the book] will feel comfortable recommending, then we've succeeded."

To further prime the promo pump, they've given guest-casting appearances to what Aglialoro says are "almost 10 personalities who have TV shows or radio shows who have a million plus followers who are going to talk to their people" about Atlas III. But it won't all be grassroots promotion—Aglialoro says he's intent on making sure the hot movies this summer have on their weekend showings a hot trailer for Atlas III.

To cement potential audience connection to the project, the producers launched a Kickstarter campaign last September that raised $446,000. Exactly as they knew it would be, this was mocked by people whose (mis)understanding of Rand only went as far as "she valorizes businessmen and the market." This led many to assume that asking people to freely support something they valued was in some sense un-Randian. Aglialoro sees it differently, as would anyone who understands Rand. Her novel The Fountainhead is a paean to an artist whose work is not rewarded by the marketplace. Rand believed in the glory of trading value—money—for value—a film the giver wants to see.

Aglialoro says he's gotten hundreds of unsolicited checks in support of this project over the decades since he got the rights to make a movie of Atlas, including one for $100,000, and is still proud of the hundreds of one-dollar contributions from people telling him, he says, that "'I want to take some value of mine and place it where I see value [his movie].'"

With DVDs and streaming (ancillary incomes he says have been rising recently) and the chance that many people will wait to binge-watch the completed trilogy when it's done, Aglialoro isn't sure that he'll lose money in the end. He's even contemplating doing a 24-episode TV remake in the future, one that could close-focus on specific themes or characters in the novel in more depth such that "people who never read the book would find it very entertaining but also say, 'I got something from that, I have a better understanding of life, better values because of that.' "

Yes, to answer a question the Atlas team is weary of answering, they did entirely recast Part III, just as they did for Part II. "Do people complain when they recast James Bond or Batman?" Kaslow asks rhetorically. (Yes, many people do, but I've met few people emotionally attached to the specific actors from earlier Atlases.) "The star of the movie is not the actors," DeSapio says. "The star is Atlas Shrugged and the ideas of Ayn Rand."

I visited the set in early February, during the last week of its shooting schedule. For days the Atlas team had taken over the entire old Park Plaza Hotel near Los Angeles' MacArthur Park, transforming it into the Wayne-Falkland Hotel, the scene of a press conference by America's leader, John Galt's apartment (I saw the hero's belt and ties in a drawer) and lab, and the torture chamber where the bad guys trap Galt, among other locations. The production team was working on a tight schedule, painting hallway walls they'd just build with just hours to spare—I accidentally put my fingerprints on a still-wet wall outside Galt's quarters.

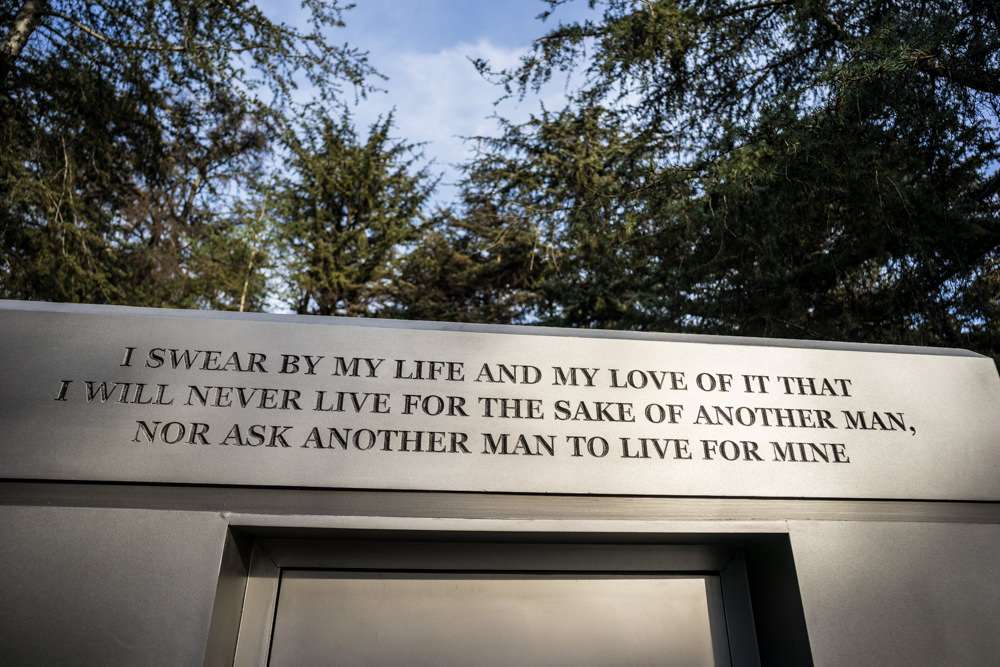

Their John Galt is Kristoffer Polaha (you might recall him as Carlton Hanson in Mad Men). DeSapio says Polaha came in understanding the nature of the Randian hero; I'm told by another insider on set that he was a fan of The Fountainhead, considering it a lifechanging experience. DeSapio says "I want every fan of Rand to hear [Polaha] say the classic Galt phrase: "I swear by my life and my love of it that I will never live for the sake of another man, nor ask another man to live for mine."

The producers are also high on their new director James Manera, a veteran of the commercial world who is also shooting a feature about Vince Lombardi. "I think that if I were asked--and I won't be!--to form the curriculum of film school," Aglialoro says, "what do you do to be a director, I would say the graduate side should be knowing how to do a high-quality TV commercial. They have to get a lot of information and a lot of communication, a lot of art and visuality in that 30 seconds or 60 seconds, and Jim Manera has won awards in that world." (Other great Americans who have expressed similar feelings about the art and significance of 30-second commercials include Stanley Kubrick and Timothy Leary.)

On my day on set, I watched for hours as they filmed the scene where John Galt's speech begins interfering with a planned televised address by America's national leader. (I also overheard a great 'only on a film set' discussion in which someone tried to assure Kaslow that in a later scene, "If you want to set the motor and the walls on fire, we can do that.")

Galt's speech is famously long—had they not condensed it, that scene alone would have been longer than most feature-length films. Manera runs his cast through what seems like just the beginning and end of it many, many times, giving direction on how quickly the leader's aides should react, where people should look. Two of the producers wonder aloud about exactly how the actors playing Dagny Taggart (the novel's conflicted heroine) and Eddie Willers (her longtime assistant), who already know Galt's voice, should properly react to hearing him break into the broadcast.

Aglialoro thinks Rand was having an intellectual "bad hair day" when she decided to valorize the term "selfishness," which he thinks blunts her message of individual achievement through freely chosen market cooperation, not "self at expense of others." Thus, he tried to make their approximately four-minute condensation of Galt's speech a bit more inspirational, a bit less condemnatory, than the novel's version. It ended (from what I could hear) with talk of how you should not in your confusion and despair let your own irreplaceable spark go out and how the world you desire can be won.

With the speech, says Kaslow, the "challenge was, you want people to feel good" and so they tried to "accentuate the positive aspects as opposed to presenting things in negative." Aglialoro mentions that "Rand had in there the mystics of the world corrupting humanity…and that would be self defeating" in getting across her message in such a tight form.

The most orthodox of Objectivists, like the ones associated with the Ayn Rand Institute (connected with Rand's heir and enforcer, Leonard Peikoff), will likely object. Aglialoro sums up his relationship with these controllers of Rand's estate as "I wish them well—we share the same ideas--and they wish us extinction." But he is sure that he can't get across Rand's message via a hopefully popular movie "by catechism. It has to be done by communication." Peikoff, from whom Aglialoro bought the film rights, has the right to see the script before shooting, but he has, Aglialoro was told, refused to read them or comment on them, merely, as Kaslow says, "cashing the checks."

On set Manera uses subtle smoke machine effects to get across the grimly decaying aura of this Randian alternate universe worn down by lack of respect for creators. As DeSapio tells me while praising Manera's direction and visual sense, "Rand hated naturalism, and it just doesn't work with Atlas. I have no question this one will be the best of the three in being closest to accurately reflecting what we [Rand fans] all wanted to see on the screen." The film is being shot entirely using a new Canon camera system called the C-500 4K.

I interviewed Dominic Daniel, playing Eddie Willers, the representative of decent, but not necessarily genius, man in the story. Daniel sees Willers as someone who slowly realizes he's been "giving his talents and ability over to people who aren't necessarily, I don't want to use the word 'deserving,' but definitely not appreciative." Willers goes through, Daniel thinks, the most wrenching change in outlook as the story progresses.

He's pleased that the movie reworked Willers' fate so he is not so much "dumped off to the side." Daniel was assigned Fountainhead in high school, and has an uncle who considers Rand his hero, and "that book spoke about individuality, finding one's own path and taking responsibility for your own life and not listening to people who say 'you owe it to us,'" a message that resonated as Daniel chose a career in the arts, not what his parents might have expected. He knows there are a lot of curious feelings and hostility toward Rand's work, and admits he's gotten "a little of that, a few friends who are like, [in a suspicious tone]: 'What's going on on set? How is it?' kind of thing. But I didn't have any reservations."

Aglialoro says he's pissed that when a previous installment premiered in D.C, "not one politician came, not one Republican or Democrat--especially the Republicans with their big mouths talking about 'I like Ayn Rand and Atlas,' not one came. They played it safe." Screw the political classes—Atlas III will premier in Las Vegas in September.

Maybe he'll make his money back; maybe he won't. This Randian businessman doesn't seem too worried about it. He finished what he started because he believed in its "purpose, which is to change people's lives for the better by [helping them] realize the opportunity and responsibility of enlightened self-interest."

Show Comments (91)