Obama Retreats From the War on Drugs

He shouldn't stop now.

The American people once elected a president who favored decriminalizing marijuana. Jimmy Carter endorsed the change in 1976 as a candidate and again after taking office. Nothing happened, and more decades have been wasted in the war on cannabis and other drugs.

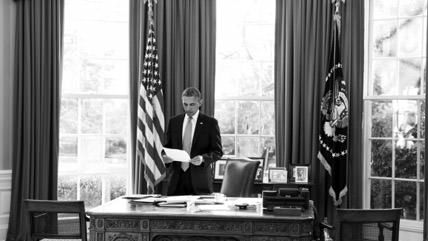

Now we have a president who, like his two immediate predecessors, got baked in his youth yet has declined to push for any major change in federal drug laws. Barack Obama, however, has indicated some willingness to dial back prohibition.

In a recent interview with The New Yorker magazine, the president said he regards smoking weed "as a bad habit and a vice" but added, "I don't think it is more dangerous than alcohol." Is it less dangerous than alcohol? Yes, "in terms of its impact on the individual consumer," Obama admitted.

He also noted the disparity of enforcement: "Middle-class kids don't get locked up for smoking pot, and poor kids do." Asked about legalization, he responded mildly that its advocates "are probably overstating the case." That's a notable departure from 2009, when he mocked a question about it during a video town hall meeting.

But a change of tone would be cold comfort without a change of policy. In some significant ways, Obama has moved away from the intolerant mindset that has afflicted every recent president going back to Ronald Reagan.

The biggest surprise is his stance toward the legalization experiments in Colorado and Washington.

When the issue was placed on the ballot, White House drug czar Gil Kerlikowske publicly rejected the idea but didn't make a big deal of it. Bill Piper, director of national affairs for the Drug Policy Alliance, told me, "His silence on those measures in 2012 was noticeable."

More important is what the administration did after they passed: It backed off. The Justice Department could have instructed federal prosecutors to go after marijuana possession and sales, to dramatize the president's stern opposition. Instead, it instructed them to let the states go their own way, focusing federal enforcement on preventing major drug trafficking and sales to minors.

Had the initiatives passed under George W. Bush, the enforcement policy would have been less indulgent.

Not standing in the way of states trying legalization is a big deal. It shows a somewhat open mind about the wisdom of the status quo and the practical effects of liberalization. Not since Carter was in the White House has an administration been willing to concede that there may be alternatives to the drug war.

If Obama really believes what he says, though, merely doing nothing is not quite enough. Getting any change in federal law through Congress is utterly beyond hope—even with 58 percent of Americans now favoring legalization of cannabis, according to Gallup. But he has some presidential authority that, unlike most of his powers, is just sitting there collecting dust.

The most obvious thing he could do is to remove the barriers to scientific research on the therapeutic use of marijuana. Anyone who wants to do such studies now faces two major hurdles: getting cannabis from the National Institute on Drug Abuse, the only approved source, and getting permission from the Drug Enforcement Administration and other agencies with a history of resistance.

Scientists say the federal weed is not good enough to be used in clinical studies. So Lyle Craker, a professor of plant sciences at the University of Massachusetts Amherst, applied in 2001 for permission to cultivate his own supply for medical research. In 2007, a federal administrative law judge ruled that allowing Craker to grow it "would be in the public interest." DEA, however, refused.

Craker is still waiting, 13 years later. So are patients who could benefit from more information about whether cannabis can cure them—or, for that matter, harm them.

Obama could order the DEA to let him proceed. He also could insist that the agency license other private production of cannabis for research. He could scrap the requirement that the Public Health Service approve all privately funded research on marijuana—a rule that, as Rick Doblin of the Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies notes, doesn't apply to other drugs, including LSD and Ecstasy.

The president could make changes like these with zero political risk. No one expects him to sue for peace in the war on drugs. But he's begun a retreat that shouldn't stop now.

Show Comments (26)