Harassed for Taking Photos

When cops can't tell a photographer from a terrorist

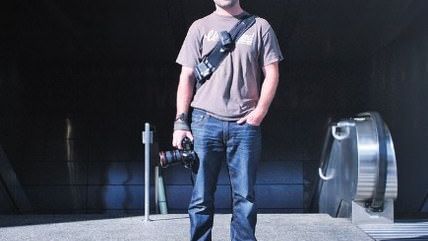

In October 2009 Shawn Nee, an award-winning photographer, was stopped by officers from the Los Angeles County Sheriff's Department (LASD) while taking pictures of turnstiles in the L.A. subway. According to the officers, Nee was engaged in "suspicious terrorist activity."

"I want to know if you are in cahoots with Al Qaeda to sell these pictures to them for a terrorist purpose," LASD Deputy Richard Gylfie told Nee, according to footage shot by a body camera Nee wears while working. Gylfie and his partner, Deputy Roberto Bayes, held Nee's hands behind his back, searched his pockets, and conducted a check to see if there were any outstanding warrants for his arrest. At one point the footage shows Gylfie telling Nee he would put him on "the FBI's hit list" if he didn't answer his questions.

"On one level you're thinking, is this really happening?" says Nee. "On another level you're thinking, this shouldn't be happening."

This sort of encounter, in which local cops harass ordinary citizens engaged in constitutionally protected behavior, has become disturbingly frequent in cities nationwide, largely because federal anti-terrorism funding has made local law enforcement agencies major participants in the War on Terror. The idea is that cops are particularly well situated to be the eyes and ears that will halt the next attack before it happens. But local police departments often lack the oversight and safeguards that could protect citizens from abuse.

Nee was not arrested or charged back in 2009, and the incident would not have had any legal ramifications if he had not filed a complaint with the LASD arguing that the officers violated his First and Fourth Amendment rights. An internal affairs investigation absolved Gylfie and Bayes of any wrongdoing; indeed, it applauded their actions. The LASD's official report on the incident calls the officers' actions "laudable" and praises their "vigilance," adding that they, "are encouraging others to be as pro-active."

Civil libertarians disagree. "Photography is not a crime; it's artistic expression," says Peter Bibring, a senior staff attorney with the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) of Southern California, who is representing Nee in his lawsuit against the LASD, along with two other photographers who experienced similar encounters. "There was no reason to believe that just because he was taking photographs he was engaged in any kind of criminal or terrorist activity."

That's not how Deputy Gylfie saw it. The ACLU discovered that Gylfie had submitted a suspicious activity report on Nee with the Los Angeles Joint Regional Intelligence Center, a "fusion center" that collects and shares data between the LASD, the Los Angeles Police Department, the Department of Homeland Security, and the FBI. Because Nee's information was submitted to the fusion center, it was available for the FBI to review and possibly add to its eGuardian database, which compiles terrorism-related information from more than 18,000 law enforcement agencies.

"This raises concerns that people who are engaged not only in lawful activity but in constitutionally protected expression are being added to this database, and we're not sure what results that may lead to," says Bibring. "What happens when that individual is stopped for a traffic violation? What happens to that individual when he tries to fly in and out of the country?"

The ACLU obtained Nee's suspicious activity report, along with reports on more than 100 incidents related to public photography that have been filed by the LASD with the L.A. Joint Regional Intelligence Center. Most of these reports document incidents in which individuals are caught snapping photos of Los Angeles-its buildings, its subways, the skyline.

Why are officers preoccupied with harassing people guilty of nothing more than an interest in the city's iconography? A 2010 LASD instructor's guide suggests that they're just following directions. Used by the department to train officers who patrol transportation hubs in Los Angeles, the guide lists "surveillance indicators" officers should be aware of, including activities as benign as photography with "high-magnification lenses" and taking pictures of railroad tracks, bus terminals, and street signs. The guide was developed in part by the U.S. Department of Homeland Security.

"The 9/11 mentality that there are terrorists everywhere has the potential to intrude on everybody's constitutional rights," says Laurie Levenson, a professor of criminal law at Loyola Law School and a former federal prosecutor. "And I don't even think it's effective law enforcement. You can end up getting so much information that most of it is not useful and you're missing the needle in the haystack."

Nee is waiting for his day in court. He is seeking damages as well as a change in LASD policy regarding the detention, interrogation, and harassment of individuals guilty of nothing more than snapping photos. The lawsuit also seeks to prevent LASD officers from arbitrarily prohibiting photography in public places.

"Eventually everything is going to be suspicious," says Nee. "And that's not the world we want to live in."

See a video version of this story here.

Show Comments (87)