Federalism and Liberty in the Supreme Court's Gay Marriage Cases

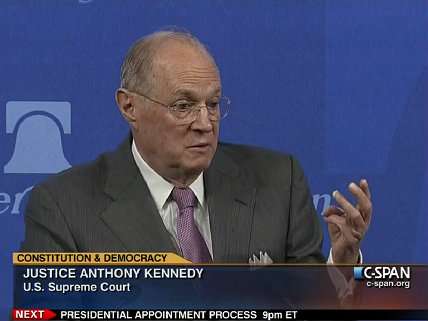

In his majority opinion today invaliding Section 3 of the 1996 Defense of Marriage Act, Justice Anthony Kennedy employed two of the most common themes in his jurisprudence: federalism and liberty. Beginning first with the observation that "the Federal Government, throughout our history, has deferred to state-law policy decisions with respect to domestic relations," Kennedy explained how DOMA's requirement that the federal government refuse to recognize a valid same-sex marriage from a state served to upset that longstanding federalist balance.

"The significance of state responsibilities for the definition and regulation of marriage dates to the Nation's beginning," he continued, strongly suggesting that DOMA might be invalidated on federalism grounds alone.

But then he pivoted. "It is unnecessary to decide whether this federal intrusion on state power is a violation of the Constitution," he wrote. That's because DOMA's infringement on the 5th Amendment is itself so severe. "Though Congress has great authority to design laws to fit its own conception of sound national policy, it cannot deny the liberty protected by the Due Process Clause of the Fifth Amendment."

In other words, the government overreached and liberty suffered. "The principal purpose and the necessary effect of this law are to demean those persons who are in a lawful same-sex marriage," he wrote. As a result, DOMA must fall. Kennedy adopted a similar approach in 2003 when he invalidated Texas' ban on homosexual conduct in the case of Lawrence v. Texas, a decision handed down 10 years ago today. "Liberty presumes an autonomy of self that includes freedom of thought, belief, expression, and certain intimate conduct," he declared at the outset of that case, before striking down the law as an illegitimate exercise of government power.

Many gay rights advocates had hoped for a similar ruling by Kennedy this morning against California's Proposition 8, the voter initiative banning gay marriage in that state. But a majority of the Supreme Court opted instead to stay clear of the pressing question of whether or not Prop. 8 violates the Constitution by ruling only on a procedural matter, thereby sending the dispute back to California and avoiding a sweeping constitutional decision one way or the other. In his dissent today in that case, Kennedy argued that the Supreme Court was wrong to avoid reaching the merits, but gave no indication of how he might ultimately vote if it did so. He reserved the word liberty for his DOMA decision alone.

Editor's Note: As of February 29, 2024, commenting privileges on reason.com posts are limited to Reason Plus subscribers. Past commenters are grandfathered in for a temporary period. Subscribe here to preserve your ability to comment. Your Reason Plus subscription also gives you an ad-free version of reason.com, along with full access to the digital edition and archives of Reason magazine. We request that comments be civil and on-topic. We do not moderate or assume any responsibility for comments, which are owned by the readers who post them. Comments do not represent the views of reason.com or Reason Foundation. We reserve the right to delete any comment and ban commenters for any reason at any time. Comments may only be edited within 5 minutes of posting. Report abuses.

Please to post comments

In other words, the government overreached and liberty suffered.

Business as usual.

"Though Congress has great authority to design laws to fit its own conception of sound national policy, it cannot deny the liberty protected by the Due Process Clause of the Fifth Amendment."

Unfortunately, "due process of law" is apparently *whatever Congress (or the President) does*. 8-(

We need not take the Supreme Court majority's concern-trolling about federalism seriously. Scalia contends that we are simply waiting for the "other shoe" - legalization of SSM throughout the country - to drop. And when that happens, the Court will say that federalism cannot protect a state which violates the fundamental blah blah blah.

In its DOMA decision, the Court went out of its way to affirm that it is perfectly cool with certain intrusions on the states' definition of marriage. To give one of many examples, it's totally OK for the feds to deny a visa to an American citizen's foreign spouse, even though the couple is validly married under state law, based on some bureaucrat's determination that the marriage was motivated by the foreign spouse's desire to live in the U.S.

So the federal government can discriminate against state-recognized marriages...except when it can't. That's totally coherent and not in the least result-oriented.

In its DOMA decision, the Court went out of its way to affirm that it is perfectly cool with certain intrusions on the states' definition of marriage. To give one of many examples, it's totally OK for the feds to deny a visa to an American citizen's foreign spouse, even though the couple is validly married under state law, based on some bureaucrat's determination that the marriage was motivated by the foreign spouse's desire to live in the U.S.

That's really a separate issue. Obviously the feds should have far less discretion on that issue, but it doesn't have a whole lot to do with today's ruling.

It has a *lot* to do with today's ruling. The Court is accepting a double standard as to which federal interferences with marriage it's willing to countenance.

Is it such a trivial matter for an American citizen to be told he has to leave his own country to be with his foreign wife (or a woman with her foreign husband) because the Supreme Court respects the privilege of the states to define marriage... but not in their case?

Did I say trivial? You, John and Tony are the champions of defeating straw men.

You said it isn't related to today's ruling, but today's ruling indulged in considerable concern-trolling about federalism. Of course, they are being insincere, so in that sense you are right, it has little to do with the immigration laws refusing to recognize marriages granted by the state. But if the Court were actually serious, this particular lacuna in its reasoning would be very significant.

Their refusal to completely overturn large swaths of immigration law, even when that was not the issue presented to them, shows how unserious they are.

The court (or more properly the different factions of the court) has a double standard on most Constitutional issues. The fact that other laws may be unjust or unconstitutional, or that SCOTUS is composed of hypocrites, doesn't mean the case was wrongly decided.

My guess as to their response to your point (not saying I agree with their reasoning) would be something along the lines of this: If people marry just to get the foreign spouse legal residence in the US, they're skirting immigration law, while the specific gender of the spouse is irrelevant in that regard.

Huh. I think I agree with Scalia. Everything Constitutional is not necessarily good, and once people accept that the government can attach benefits or penalties to the simple existence of a contract between two individuals, the government (state or federal) can put whatever arbitrary limits they wish on the qualifications. Government out of marriage!

Ultimately, this may have to happen. You just know that the next challenge is to bans on polygamous marriage, and it'll be interesting to see otherwise statist gay marriage supporters contort themselves to explain why the principles they just argued for don't also apply to polygamists.

The states, yes. The feds no, as they're not granted that power by the Constitution

I haz a happy fer teh gayz!

How happy?

I wonder how many of the people cheering today's decision, with its emphasis on the Court's "primary duty" to apply the constitution to unconstitutional legislation, were telling us a year ago that any Justice who dared to strike down legislation passed by majorities in both houses of Congress (Both Houses!!!) was a shameless political hack who'd be undermining the Court's credibility for centuries to come.

Ha ha, pay no attention to that overlapping Venn diagram!

Legislation passed by majorities in both houses of congress can be, and often is, unconstitutional.

For some it's only a problem when it affects their friends' weddings.

Too true.

Of course. I am merely pointing out the outcome-oriented flip-flopping among the liberal commentariat.

Most of the Facebook postings on this that I've seen are cheering the ruling (fine with me), but I'm skeptical as to the ability of these people to understand why the Court ruled this way. It seems like most of them think the decision was made on purely emotional grounds (because that's how they themselves arrived at their viewpoint).

Understanding why is critically important to having principled views. These people don't seem to have any principles other than "if I agree with it, it's cool!"

Yeah. I wouldn't have thought DOMA being ruled unconstitutional would make me feel depressed, but it has.

I know - I feel the same way. And it's not because of the ruling itself, it's the overly-emotional reaction to a purely Constitutional argument.

One they don't understand, and wouldn't agree with in any other circumstance (except perhaps medpot) even if they did understand why it was ruled unconstitutional.

That describes pretty much every decision the Supreme Court hands down on hot-button issues.

Idiotic reporters for the Washington Post make grand pronouncements about what the decision means, without actually bothering to try and explain the reasoning of the decision.

Of course, a lot of the yahoos who get all worked up on the Internet about hot-button social issues do seem capable of grasping the concept of federalism, or simply lack principles and are willing to apply it situationally.

"don't seem capable", that is. This particular Internet yahoo is guilty of typing too fast.

40 lashes for you!

That's exactly what some dumbfuck proudly and openly did about SCOTUS ruling section 4 unconstitutional in the VRA.

And I quote "So don't get bogged down in the legal arguments offered by Justice Roberts." They purposefully WANT their fellow liberals to completely dismiss the legal reasonings behind particular decisions specifically in order to justify their feeling about the issue.

The law doesn't matter. Only my feelings matter.

So what do these rulings imply vis a vis a legally married same sex couple moving to a state which does not recognize such marriages?

My understanding is that right now, states that don't recognize ssm's still don't have to, just the fedgov does. I may be mistaken though.

As far as I know, that's correct. A different section of the DOMA that was not challenged in this lawsuit says that states not allowing gay marriage do not have to recognize gay marriages granted in other states.

I'm sure that'll be challenged in another lawsuit, if it hasn't been already. However, such a challenge is on thinner ground, since the federalism issues are less present--the federal government in that DOMA provision isn't forcing the states to do anything.

Exactly, such a suit might find Kennedy on the other side of a 5-4 decision, upholding that section of DOMA.

If the commerce clause can be stretched to benefit the will of the Legislature, why is the Due Process clause considered sacrosanct?

Are you kidding? The Due Process Clause has been stretched to crazy lengths over the years. It's hard to even say exactly what it is, anymore.

I guess it would be too much to ask for enough logical consistency that either the Commerce Clause should be brought back under its original, restrictive definition or the Due Process Clause should be expanded in order to allow for judicial deference to the Legislative Branch, but such inconsistency prohibits me from being to celebratory about the DOMA decision.

Due process is entirely about the executive branch. The problem is that the very term is ambiguous and context-specific. There's almost no way to make it totally constistent.

The Commerce Clause began to be distorted almost from its inception. McCulloch v. Maryland was decided only about 20 years after the Constitution was ratified, and it was the case that introduced the notion that the feds can regulate activities that "affect" interstate commerce, even if the activities themselves are purely intrastate or are not 'commerce'.

I'm not sure how you get back to the founders' intentions for the Commerce Clause.

It's too late for that. Much law would have to be overturned, and that just isn't going to happen.

Kennedy "pivoted" so many times, he must have thought he was playing basketball, rather than ruling on constitutional constraints.

Fairly good results from the ruling, but a terrible opinion, fraught with "ringing bells", Cloaks of Authority, "animus", and vague efforts to avoid saying anything substantive.