Are Mass Shootings Becoming More Common in the United States?

Making sense of the data

Are mass shootings becoming more common in United States? Brad Plumer of The Washington Post thinks so:

Of the 12 deadliest shootings in U.S. history, six have taken place since 2007. (The Newto[w]n school shooting will likely rank second on that list.) Mass killings appear to be on the upswing -- even as other types of homicides and violent crimes are becoming less frequent.

David Brooks highlighted this discrepancy back in July. For much of the 20th century there were, on average, a handful of mass killings per decade. But that number spiked in 1980, and kept rising thereafter. In the United States, there have now been at least 62 mass shootings in the past three decades, with 24 in the last seven years alone. This has happened even as the nation's overall violent crime and homicide rates have been dropping.

Plumer is conflating several stories here. The Brooks column opens with a mass murder in Germany in 1913 and refers to killings in Norway and Korea, so he's telling a global story, not simply an American one. Plumer also slips from the phrase "mass killings" to "mass shootings," but these are not the same category, as any fire marshal could tell you.

But the biggest problem with the passage is the slim evidence that the upward trend exists. As the AP pointed out this weekend,

those who study mass shootings say they are not becoming more common.

"There is no pattern, there is no increase," says criminologist James Allen Fox of Boston's Northeastern University, who has been studying the subject since the 1980s, spurred by a rash of mass shootings in post offices.

The random mass shootings that get the most media attention are the rarest, Fox says. Most people who die of bullet wounds knew the identity of their killer….

Grant Duwe, a criminologist with the Minnesota Department of Corrections who has written a history of mass murders in America, said that while mass shootings rose between the 1960s and the 1990s, they actually dropped in the 2000s. And mass killings actually reached their peak in 1929, according to his data. He estimates that there were 32 in the 1980s, 42 in the 1990s and 26 in the first decade of the century.

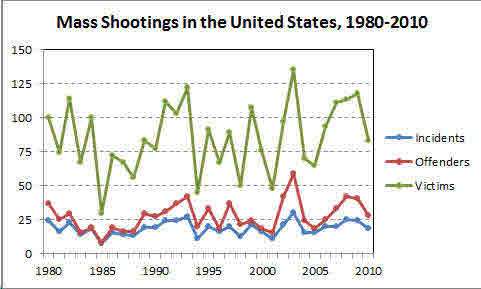

Fox made his point in greater detail in August. In the last three decades, he noted, the figures for gun homicides that kill at least four victims look like this:

"Without minimizing the pain and suffering of the hundreds…who have been victimized in senseless attacks, the facts say clearly that [there] has been no increase in mass killings," Fox wrote. When clusters of incidents occur close together, he added, that likely reflects a mixture of copycatting and coincidence.

Since his chart ends in 2010, it doesn't address the unusually high number of casualties from mass murders that we've seen in 2012. But it does suggest that an increase this year is not an ongoing trend; or, at the very least, that it's too soon to tell a new trend from another cluster. (*) As terrible as these crimes are, they represent a very small fraction of the country's murders, and it's easy to read too much into their fluctuations, a point Michael Siegel made in a critique of a much-cited Mother Jones story on the subject. (* Correction: The number of deaths from mass shootings in 2012 thus far is reportedly 68, which is actually less than Fox's figure for 2010. It is the total number of casualties -- dead and injured combined -- that appears to be higher than usual.)

In a more recent column, written after Friday's massacre of children in Connecticut, Fox argued that "if it seems like these dreadful crimes are occurring more frequently, it is really the immediacy and pervasiveness of media coverage that creates the impression. And thanks to state-of-the-art technology, it can feel as though the tragedy happened in your own backyard." Duwe has addressed the media coverage too, pointing out in a 2005 paper that mass murders in the 1920s and '30s were more likely to take place within families or during the commission of another felony. These are not the kinds of killings that tend to attract a high level of press attention.

That said: While there's a lot to object to in the media coverage of the last few days -- the inaccuracies reported on the day of the massacre, the exploitative intrusions on grieving people's privacy -- this feeling that the crime took place in our backyard isn't a bad thing in itself. It represents empathy, and when the press amplifies our empathy, it's doing good. But it's also important for the press to give us a context for that empathy, lest those natural feelings for the victims and the people who loved them turn into an irrational fear that the next victims will be our own children or ourselves. Look at the ways so many schools locked down after Columbine: the increase in inflexible zero-tolerance policies, the speed-up in the school-to-prison pipeline. Those changes made a lot of students less secure, not more. And they were driven by contextless, free-floating fear. Empathy sí, paranoia no.

Show Comments (179)