Why the 'Automobile Exception' Does Not Allow Warrantless GPS Tracking of Cars

Last year, after the Supreme Court ruled in U.S. v. Jones that tracking a suspect's car by attaching a GPS device to it constitutes a "search" under the Fourth Amendment, many people (including me) assumed that meant police would have to obtain a warrant before undertaking such surveillance. None of the recognized exceptions to the warrant requirement seemed to apply, and police did not even have a plausible argument that the need to seek permission from a judge would impose an intolerable burden on their work. In fact, the cops who tracked the defendant in Jones did obtain a warrant but failed to install the tracking device before the warrant expired. Still, the Supreme Court did not explicitly say a warrant was necessary for GPS-aided vehicle tracking. It declined to address the question of whether such surveillance could be "reasonable" without a warrant because the government had failed to make that argument in the lower courts. Yesterday, as Ron Bailey noted this morning, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 3rd Circuit became the first federal appeals court to squarely address that issue, ruling in U.S. v. Katzin that police do need a warrant before planting a GPS tracker on a suspect's vehicle.

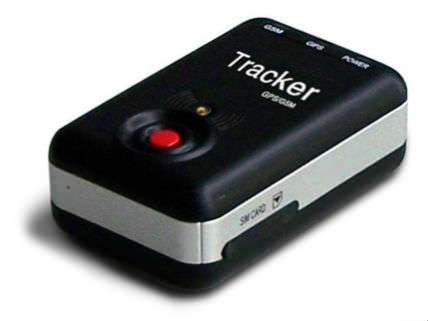

The case involved a joint state and federal investigation into a series of pharmacy robberies in Delaware, Maryland, and New Jersey. FBI agents attached a GPS device to the undercarriage of a van belonging to their main suspect, Harry Katzin, while it was parked on a street in Philadelphia and tracked his movements for two days before deciding they had enough evidence for an arrest. A federal judge, concluding in light of Jones that the FBI should have obtained a warrant, excluded the surveillance evidence. A three-judge appeals court panel unanimously agreed that a warrant was constitutionally required, although one judge thought the evidence should have been admitted anyway under the "good faith" exception to the exclusionary rule, since the surveillance occurred before Jones.

The government's most plausible-sounding argument for deeming the FBI's surveillance constitutional was that attaching a GPS device to Katzin's van was covered by the "automobile exception," which allows police to search a car without a warrant when they have probable evidence to believe it contains contraband or other evidence of a crime. That exception, originally based on the concern that a car could easily be moved to a different jurisdiction by the time a warrant was obtained, was later justified by the argument that people have lower expectations of privacy in their cars than they do in other settings (such as their homes). But such searches always have been limited to looking in a car for evidence it currently contains.

"Attaching and monitoring a GPS tracker is different," the 3rd Circuit observes. "It creates a continuous police presence for the purpose of discovering evidence that may come into existence and/or be placed within the vehicle at some point in the future….A GPS search extends the police intrusion well past the time it would normally take officers to enter a target vehicle and locate, extract, or examine the then-existing evidence….Simply put: attaching and monitoring a GPS tracker does not serve the purposes animating the automobile exception."

It seems unlikely that the Supreme Court will find the argument based on the automobile exception (or any of the other excuses offered by the government) more persuasive than the 3rd Circuit did. A more important question raised by Jones is whether the Court will interpret the Fourth Amendment to cover forms of surveillance that do not require the physical intrusion that Justice Antonin Scalia emphasized in his majority opinion. The government can obtain similar information by tracking cellphones, activating GPS beacons built into cars, or even monitoring people with camera-equipped drones. None of those methods requires trespassing on anyone's property. Judging from the positions they took in Jones, at least five justices are prepared to say such hands-off techniques also implicate the Fourth Amendment.

Show Comments (6)