The Volokh Conspiracy

Mostly law professors | Sometimes contrarian | Often libertarian | Always independent

Final Published Version of "The Constitutional Case Against Exclusionary Zoning" Now Available

In this Texas Law Review article, Josh Braver and I argue that most exclusionary zoning violates the Takings Clause of the Fifth Amendment.

The final published version of my article "The Constitutional Case Against Exclusionary Zoning" (coauthored with Josh Braver) is now available for free download on SSRN. Here is the abstract:

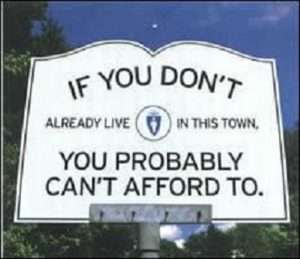

We argue that exclusionary zoning—the imposition of restrictions on the amount and types of housing that property owners are allowed to build— is unconstitutional because it violates the Takings Clause of the Fifth Amendment. Exclusionary zoning has emerged as a major political and legal issue. A broad cross-ideological array of economists and land-use scholars have concluded that it is responsible for massive housing shortages in many parts of the United States, thereby cutting off millions of people – particularly the poor and minorities - from economic and social opportunities. In the process, it also stymies economic growth and innovation, making the nation as a whole poorer.

Exclusionary zoning is permitted under Euclid v. Ambler Realty, the 1926 Supreme Court decision holding that exclusionary zoning is largely exempt from constitutional challenge under the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment, and by extension also the Takings Clause. Despite the wave of academic and public concern about the issue, so far, no modern in-depth scholarly analysis has advocated overturning or severely limiting Euclid. Nor has any scholar argued that exclusionary zoning should be invalidated under the Takings Clause, more generally.

We contend Euclid should be reversed or strictly limited, and that exclusionary zoning restrictions should generally be considered takings requiring compensation. This conclusion follows from both originalism and a variety of leading living constitution theories. Under originalism, the key insight is that property rights protected by the Takings Clause include not only the right to exclude, but also the right to use property. Exclusionary zoning violates this right because it severely limits what owners can build on their land. Exclusionary zoning is also unconstitutional from the standpoint of a variety of progressive living constitution theories of interpretation, including Ronald Dworkin's "moral reading," representation-reinforcement theory, and the emerging "anti-oligarchy" constitutional theory. The article also considers different strategies for overruling or limiting Euclid, and potential synergies between constitutional litigation and political reform of zoning.

Josh and I have also published a nonacademic version of our thesis in an article in the Atlantic.

This project is an exercise in cooperation across ideological and methodological lines. Josh is a progressive and a living constitutionalist. I'm a libertarian generally sympathetic to originalism. If we can nonetheless agree on this important issue, we hope others can too!

Editor's Note: We invite comments and request that they be civil and on-topic. We do not moderate or assume any responsibility for comments, which are owned by the readers who post them. Comments do not represent the views of Reason.com or Reason Foundation. We reserve the right to delete any comment for any reason at any time. Comments may only be edited within 5 minutes of posting. Report abuses.

Please to post comments

I see a big inconsistency in failing to argue that nuisance laws violate the takings clause. After all, these impose a regulatory restraint on ones ability to use ones land as one pleases every bit as much as zoning laws. And what right do neighbors have to have any sort of say in or opinion on what uses of land do and do not annoy them?

I mean, take foul odors, a classic nuisance. Why should neighbors have any more right to have an aesthetic opinion on what’s a good or a bad smell - what is and isn’t pleasing to the nose - than on what is and isn’t pleasing to the eye? It’s not like one is any more objective than the other.

Professor Somin makes a reasonable policy argument that zoning laws have gone too far and less regulation would, at least in some respects, be better policy. But his constitutional argument just doesn’t fly. It’s nothing more than a policy argument dressed up in legal-sounding language, an attempt to get judges to do what he can’t persuade legislatures to do. He has been having some success with legislatures lately. I suggest continuing in that direction rather than trying to bypass the democratic process and have judges misuse their power to ram his policies down peoples’ throats. The Constitution no more requires libertarianism than it requires socialism or any other philosophy of government.

Would this be limited to zoning laws put into place AFTER someone already owns a property? Seems to me that zoning laws in place when someone buys the property would be just fine, as the "taking" occurred before the property was bought.

If that is not the case, then HOA restrictions would also be problematic. Or is there a difference between a city (government) and a HOA (contractual) limitation?

I will have to read the article.

That does seem to be a huge hole in their argument. Land is bought and sold knowing the zoning restrictions, and thus that is factored into the price. There is no "taking" if the landowner never had the think to be taken in the first place. Also it is very common for land to be re-zoned from agriculture/rural to residential before the houses are built, and thus increase the value of the property. If a piece of land is re-zoned in a way that makes the land less valuable, then it could be a takings, but that is the only way.

I do dislike the way zoning is done in the US. It has created the car centric cities and towns that are awful.

It isn't zoning. Consumer preferences led to car centric cities and towns. Most people prefer to live in suburbs and exurbs where they can have large homes on big lots with multicar garages. Having to drive is a small price to pay for increased room and more privacy.

Somin persists in a fictionalized world view in which zoning is imposed by uncaring governments on unwilling landowners. The reality is quite different. If the landowners opposed the zoning, the zoning would change. Thus, the YIMBY "solutions" that Somin prefers are imposed from outside usually by the state over the opposition of the locals.

No, Professor Somin understands very well that existing landowners like zoning laws, just he understands very well that existing citizens like immigration restructions. That’s WHY he thinks they should be struck down. He thinks they benefit existing landowners (and citizens) at the expense of people who would like to move in, e.g. the homeless and immigrants. And he thinks that “that’s unfair” to the homeless and immigrants, hence an equal protection violation. That’s his basic argument. He WANTS an imposition from outside to the (as he sees it) unfairness that the existing landowners, the insiders, are doing to the outsiders. Any time one appeals to courts, that what one is doing.

As I’ve said anove, it’s a perfectly good moral/policy argument. We have a lot more people than a century ago, so maybe people just can’t expect to have as much land per person as they did a century ago and the law supporting the status quo should be changed. It’s just that every time somebody thinks something is unfair, it doesn’t create a constitutional issue. Almost every law is unfair in the eyes of at least some people. It’s par for the course.

Palazzolo v. Rhode Island addressed your question. Palazzolo was allowed to sue over a regulation that existed before he acquired his interest.

Good point. Thanks.

So, it goes to the next question. If zoning is a taking, whether the zoning happened before or after the property was purchased, why would zoning laws be treated any differently from HOA restrictions, or for that matter, restrictive covenants. Indeed, contract agreements between landowners and renters would be called into question. For example, why should a contract between a sandwich shop and a landlord to not allow any other sandwich shops in the shopping mall be enforceable?

It seems to me that the only restriction that is problematic is one where it is imposed by the government. I would note that Palazzolo has an issue. Assume there was a taking and the government paid the previous landowner for it. Could a subsequent landowner claim that there was more taking and as for further compensation?

Also, what would happen if someone bought land with zoning that essentially made the land worthless for $1, and then sued for the taking?

It is a slippery slope.

In Prof Somin's rigid libertarian framework, HOAs are hunky-dory because they are private contracts, as opposed to govt regulations. Never mind that they are functionally indistinguishable from zoning regs except for often being far more intrusive and annoying.

Here is how I think the system should work procedurally, leaving aside the merits of a takings claim.

I want to build a house on a lot currently zoned for Angora goat farming. I buy the lot for $1,000 at my own risk. The town refuses to grant me a building permit. I sue. The court rules the zoning regulation illegitimate, a bad NIMBY rule rather than a good public order regulation. The value of the lot is $1 million without regulation but $1 with regulation. The town cuts me a check for $999,999. The town records the judgment as a deed restriction. When I sell the property the new owner is bound by the deed restriction just like I am bound to respect my neighbor's recorded easement over the edge of my lot.

Or I lose the taking case. The town owns me nothing. I sell the lot for $1. I am out $999 plus legal costs. A copy of the judgment can be recorded as notice to future buyers that the goat restriction is a legitimate public order regulation and not government tyranny.

And then the town changes zoning from goats to sheep and a new cycle begins.

How about. . . You buy the lot for $1,000, you win the takings case, the lot is now worth $1,000,000. You get the benefit of the new regulations. You pay the previous owner $999,000, less the litigation costs. Then, you don't get a windfall. Or, maybe you get 10% of the increase in value to pay you for your trouble.

I've heard of land being sold with the price contingent on regulatory approval of development plans. If the contract is worded wrong it becomes an illegal bet on regulatory action. I think the better approach is to pay for an option to buy at a fixed price.

It is and awful and badly written decision. He bought land that was mostly protected wetland, and wanted to fill in the wetland. He claimed that the potential value that the land would have if he could fill in the wetland is a taking. Makes zero sense.

You may disagree with it, but it makes sense. The position is that any restriction whatsoever on your use of land for any purpose you want is a taking.

Hence my first comment, that if that’s the case nuisance laws are equally takings. If Professor Somin’s logic is taken seriously, landowners ought to be able to routinely blackmail their neighbors into paying them for not putting toxic waste dumps or some similar horrible on their property, shaking them down for a payout.

Professor Somin would probably say that uses of land that “really” annoy the neighbors are exempt. The flaw with Professor Somin’s reasoning, here as often, is his over-confidence in the supreme correctness of his ideology, particularly its ability to know what “really” does and doesn’t annoy the neighbors far better than the neighbors do.

This is a problem with classical libertarianism in general. It makes assumptions about the way people think and what their interests are based on the way the ideology says people OUGHT to think.

But people often just don’t think the way Professor Somin’s ideology says they should think, and don’t think their interests are what Professor Somin says they should be. Whenever Professor Somin notices this, and indeed he sometimes does, you can count on him to write a post about “political ignorance” or similar explaining that people are just too ignorant to understand what their interests really are.

That is, Professor Somin has taken some cognizance of the revolution in thinking about economics that peole like Amos Tversky and Daniel Kahneman have effected. Until quite recently economics was sort of a branch of mathematics, in which people deduced how people would behave based on axioms about how they ought to behave, being careful to apply some impressive-looking mathematics along the way. Using impressive-looking mathematics was sine qua non, essential to demonstrate you were smart and therefore capable of being right.

Earlier people had proposed learning about how people behave by observing them and seeing what they do. But as Larry Sommers once explained, economists were able to shoot that down by looking down their academic noses and hurrumphing. These people aren’t using any fancy mathematics! So they must be dumb. And all the smart people knew that dumb people are wrong. Only smart people are right.

Daniel Kahneman’s genius was to come up with fancy mathematics that could be attached to Tzi Tversky’s observational approach, which before he began collaborating with Kahneman hadn’t gotten him very far. Once Kahnemann had published a mathematical basis for Twersky’s ideas, economists realized that smart people were criticizing them. So they started paying attention. This led them to realize that their assumptions about how people think and behave are just wrong.

Professor Somin can be thought as a sort of transitional figure between the old prescriptive and the new descriptive approaches. His mind has wrapped itself around the old prescriptive axioms to the point where they. to him, are his reality. Yet he’s aware they don’t actually describe how people actually behave.

His solution to the gap is to say that when people don’t behave the way the smart people’s prescriptive logic says they should, people are being dumb (ignorant or whatever). And generally, his solution is usually that someone from outside, usually courts since his field is law, ought to FORCE them to behave, or at least to structure their laws, the way the smart people say they should. For their own freedom, of course. After all he is a libertarian.

As Larry Sommers explained, the idea that the dumb people might know something the smart people don’t, and that might explain why they don’t behave as expected, just never seems to enter the smart people’s minds. Professor Somin, being smart as a whip, continues that tradition.

"landowners ought to be able to routinely blackmail their neighbors into paying them for not putting toxic waste dumps or some similar horrible on their property"

A conservation organization had land in western Massachusetts. The organization threatened to clear the forests and develop its land. A California company paid for a conservation easement which turned into carbon credits. On paper the forests were saved. In reality the forests were never in danger.

If exclusionary zoning becomes a compensable taking a whole lot of other regulations become compensable takings. There would be a major shift in takings law.

That is the other gigantic flaw in Prof Somin's argument. Takings are not unconstitutional in the sense that they can be "struck down" by the courts. Rather, the remedy is compensation. And since the purported taking affects everyone in the community more or less equally, the compensation should be a wash.

My town switched from one acre to two acre zoning decades ago. There are a lot of older houses on one acre lots. If there is a constitutional right to build one house per acre only owners of newer houses get compensation from owners of older houses. If there is a constitutional right to build any house that fits the money flows in a different direction.

Would I only be eligible if I applied for a building permit and the town turned down my apartment complex? I would want to get my money early. Once the neighborhood is full of McMansions instead of trees my lot would be worth less.

The good professor also ignores the statute of limitations issues.

Bigger picture, he has a bit of a talismanic/cargo cult view of real estate. He seems to think that land in desirable neighborhoods is desirable per se, ignoring the fact that the zoning restrictions are one of the main factors that make the land desirable in the first place.

A better use of his time would be to figure out how to make once-desirable real estate desirable once more. Detroit and the rest of the Rust Belt, I'm looking at you.

Somin's recent fixation on zoning, which has existed relatively uncontroversially in this country for a century or so, is due to his religious zeal for unchecked, unlimited immigration. Anyone with even a basic grasp of the concept of supply and demand understands that a massive, unprecedented influx of individuals to a location will drive up housing costs in that location, but as Somin's articles of faith forbid him from acknowledging any negative consequences of unlimited immigration, he must find another culprit for skyrocketing housing costs, and he has settled on zoning as that culprit.

Somin pays a lot of lip service to property rights, but one he never mentions is perhaps the most important, the right of quiet enjoyment in one's own property. Zoning is merely a natural extension of one of the most ancient concepts in common law, the law of nuisance. Does someone have a right to open a slaughterhouse in a residential neighborhood? Does he have a right to open a bar and host scores of loud, rambunctious drunks all night? Does he have a right to an unkempt lawn strewn with auto parts? Perhaps Somin believes he does, but I suspect few would agree with him, "scholars" or otherwise.

See my comments above. Based on Professor Somin’s past posts, he would argue that what the kinds of zoning laws he dislikes forbid aren’t “really” nuisances. He is confident he knows what is “really” a nuisance and what isn’t. And if others disagree, he is confident they are simply wrong, likely because they are igjorant.