The Volokh Conspiracy

Mostly law professors | Sometimes contrarian | Often libertarian | Always independent

Glossip v. Oklahoma: The Story Behind How a Death Row Inmate and the Oklahoma A.G. Concocted a Phantom "Brady Violation" and Got Supreme Court Review (Part II)

Glossip and Oklahoma have no response to the fact that that Glossip's defense team knew all about the allegedly "withheld" Brady information.

In yesterday's post, I discussed Glossip v. Oklahoma—a case that the Supreme Court will hear next Wednesday about allegations that prosecutors withheld evidence in a death penalty trial. In that post, I reviewed my amicus brief for the murder victim's family, which contains extensive documentation proving that the prosecutors never withheld any evidence. In this second post, I discuss Glossip's and Oklahoma's (non)responses to the facts that I presented. The parties' failure to respond confirms that their Brady claim is concocted and that they are forcing the victim's family to endure frivolous litigation. Tomorrow, in my third and final post, I will explain why courts should be cautious before accepting an apparently politically motivated confession of "error" from a prosecutor.

In Glossip, the underlying question before the Supreme Court concerns whether state prosecutors withheld evidence from Glossip's defense team before his 2004 trial. In that trial, Glossip was found guilty of commissioning his friend, Justin Sneed, to murder Barry Van Treese. Glossip was sentenced to death. Now, nearly two decades later, Glossip argues that newly released notes from the prosecutors show that they withheld information about Sneed's lithium usage and treatment by a psychiatrist. And, curiously, Oklahoma Attorney General Gertner Drummond agrees. Drummond has joined Glossip in asking the Supreme Court to overturn the conviction and capital sentence.

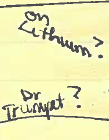

As I reviewed yesterday, Glossip's and General Drummond's argument rests primarily on four handwritten words in prosecutor Smothermon's notes:

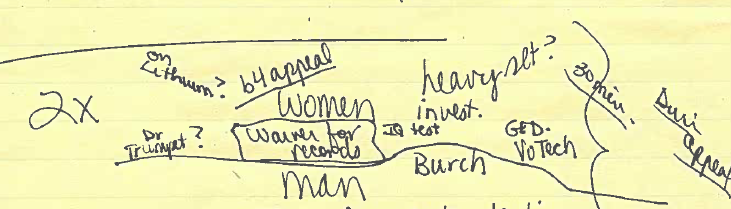

According to Glossip and General Drummond, these few words "confirm" Smothermon's knowledge of Sneed's treatment for a psychiatric condition by lithium by a "Dr. Trumpet" (later claimed to be a Dr. Trombka). But stepping back and reading the notes in context reveals a much different interpetation. Here are Smothermon's notes surrounding the four words in question:

In yesterday's post, I explained that looking at all of her notes reveals that Sneed was merely recounting what the defense team was questioning him about—not what the prosecutors had discovered. The defense team interview is reflected in the reference to "2x" (two interviews), including one by "women" that was "b4 [the] appeal" who were an "invest[igator]" and a person involved in the "appeal."

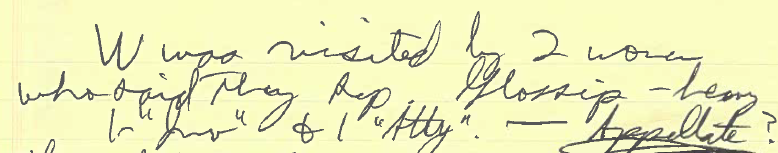

To the extent any question remains, the corresponding notes from the other prosecutor at the interview (Gary Ackley) show even more directly that Sneed was simply recounting a defense interview. The first line of Ackley's notes from the Sneed interview reads "W was visited by 2 women who said they rep[resented] Glossip - heavy—1 "inv" & 1 "Atty" Appellate?" Read for yourself:

As I pointed out yesterday, if the prosecutors' notes record what happened during a defense interview, obviously no Brady violation could exist. Because the prosecutors were simply recording what a state's witness recounted about questions asked of him by the defense team, the notes cannot contain information withheld from the defense.

In today's post, I review Glossip's and General Drummond's failure to respond to these facts. As with yesterday's post, today's post summarizes my amicus brief and also additional factual material contained in an appendix to my brief (linked here as a single document).

Glossip and General Drummond contend that the four words in the notes mean that the prosecutors possessed information that they should have disclosed to the defense. My contrary interpretation prompts the obvious question of what do the prosecutors say their own notes mean. The authors' explanation of what their own handwriting means would seem to be at least relevant to the discussion. But, surprisingly, General Drummond has not even asked the prosecutors what their notes mean.

Here's the story of behind Drummond's remarkable lack of curiosity:

Shortly after assuming office in January 2023, and perhaps sensing political advantage, General Drummond ordered an investigation into Glossip's conviction by an allegedly "independent" investigator, Rex Duncan. Duncan, its turned out, was a lifelong friend and political supporter of Drummond. General Drummond paid Duncan handsomely to produce a report on the case. But Duncan's report relied almost completely on an earlier report from the anti-death penalty law firm, Reed Smith. Duncan actually cut and pasted sections from the Reed Smith report directly into his.

In preparing his report, Duncan interviewed Smothermon twice. But Duncan never substantively explored what her notes meant. First, on March 15, 2023, Duncan spoke to Smothermon for about thirty minutes. During that interview, Duncan did not ask Smothermon about the notes in question, as confirmed by an email Smothermon immediately sent to the Attorney General's Office.

Second, on the next day, March 16, 2023, Duncan briefly called Smothermon back. During that three-minute call, Duncan conveyed an interpretation of the notes provided by Reed Smith. Duncan asked Smothermon about a reference in her notes to a "Dr. Trumpet." Smothermon then asked to see the note in question, which she had written about two decades earlier. Duncan responded there was "no need" and quickly ended the call. The entire call took about only three minutes. Smothermon then sent another contemporaneous email to the A.G.'s Office, memorializing that this call was abbreviated and non-substantive.

Since then, General Drummond has been asked (at least) three times to talk to Smothermon and Ackley about what their notes really mean—but he has obstinately refused. First, in May 2023, prosecutors at an Oklahoma District Attorney's Association (ODDA) meeting asked General Drummond personally to talk to the two prosecutors about their notes. ODDA prosecutors told Drummond that because he had never spoken with Smothermon or Ackley, he could not know what their notes meant. Drummond reportedly responded: "I accept that criticism." Drummond was also told that if he spoke with Smothermon, he would learned that her notes were about what Sneed remembered about his meetings with defense attorneys. Drummond did not respond to this concern.

Second, on behalf of my pro bono clients (the Van Treese family), in a telephone call with General Drummond on May 24, 2023, and a follow-up letter the next day, I said that Drummond should talk to Smothermon and Ackley about the true meaning of their notes. See May 25, 2023 Letter at 2 ("I believe that if you talk to the prosecutors who took the notes (Connie Smothermon and Gary Ackley), you will be able to quickly confirm that the notes recount what the defense knew—not what prosecutors knew."). Drummond's response to me (contained in the link above) ducked the subject. In the sixteen months since, Drummond has not followed up my suggestion that he go to the source of the notes.

And third, Smothermon herself has contacted the Attorney General's Office and asked the Office to review the notes with her. General Drummond's Office has declined.

In sum, despite repeated requests, the General Drummond has not discussed with the prosecutors their notes, much less attempted to discuss what is apparent from their face—e.g., that the notes merely describe what happened when Sneed was "visited by 2 women who said that they rep[resented] Glossip." Against this backdrop, the reasonable conclusion is that Drummond is not seeking to determine what the prosecutors' notes really mean. Instead, he remains willfully blind to the facts.

After I filed my amicus brief pointing all this out to the Supreme Court, General Drummond filed a reply brief. But he did not respond specifically to my arguments, including my detailed examination of the text of the notes in question. Instead, all that Drummond said was that my brief "offer[ed] alternative explanations for the notes by reference to extra-record materials." (Okla. Reply at 9)

General Drummond's reply is deceptive. First, as explained this post above and in my post yesterday, my brief offered an "alternative explanation" to Drummond's reading of prosecutor Smothermon's notes based on the notes' text. For example, the notes refer to "on lithium?" and "Dr[.] Trumpet?" Drummond omits the two question marks from his brief, which obviously suggest lack of certainty and point to Sneed being asked questions. Drummond also fails to explain who the "women" in the notes might be … other than the two women on the defense team who I have identified. And clearly these notes are in the record—they are the very notes that Drummond claims constitute grounds for reversal.

Second, General Drummond never discusses the parallel, confirming notes taken by prosecutor Ackley, who was seated next to prosecutor Smothermon during the Sneed interview. Drummond does not deny that the notes I presented to the Supreme Court are, in fact, Ackley's notes. Instead, Drummond apparently takes the position that Ackley's notes are "extra-record materials"—a convenient omission from the record, because it was Drummond himself chose to leave them out! And in any event, when it is now clear that Ackley's notes are highly relevant to the issue pending before the Court, why doesn't Drummond admit that he possesses in his Office's files parallel notes fully confirming my interpretation of Smothermon's notes?

It turns out that General Drummond has included at least part of Ackley's notes in the record. (JA939, discussed in my brief at 11 n.6). Accordingly, it is appropriate for the Supreme Court to look at the rest of Ackley's notes under the doctrine of completeness, recognized in both federal law (Federal Rule of Evidence 106) and state law (Okla. Stat. tit. 12 § 1207).

In addition to ignoring the notes' text, General Drummond fails to discuss what the prosecutors themselves say their handwritten notes mean. Drummond seem to think it is enough to say that the prosecutors' interpretation is "extra-record"—which is just another way of saying that he has contrived to remain willfully blind to avoid learning what the two prosecutors say their own scrawled notes mean. The Supreme Court has granted certiorari to review Glossip's and General Drummond's claim that the prosecutors' notes reflect information that the prosecutors knew and intentionally withhold from the defense. It is extremely odd to have an entire case move forward without Drummond and Glossip even telling the Court what the prosecutors themselves say their writing means.

As recounted in my amicus brief, the prosecutors say that their notes mean exactly what their text indicates. Smothermon says her notes recorded that Sneed was recounting what defense team members were asking him:

Sneed answered "2X" to my question of whether anyone else had spoken to him which was my usual question at the conclusion of an interview with an in-custody witness. Sneed told us … [t]he first visit was from two women before his appeal (of his first conviction). One he described as heavyset investigator. They asked him to sign a waiver for records—IQ test, GED, VoTech, and asked him questions about lithium and Dr. Trumpet. The question marks after those two words indicate that the women asked him those questions.

And Ackley likewise says that his notes reflect Sneed was recounting a defense interview:

[My] notes reflect that Sneed (W-witness) was visited by 2 women who said they represented Glossip, one was heavy, an investigator and one was an attorney. I noted appellate as a thought to the identity of the visitors. Sneed said the visit lasted about 30-40 minutes. They asked Sneed to sign a waiver so they could review his records regarding IQ tests, GED, etc. With an arrow, I noted Sneed said "on lithium when administered" regarding the visitor's questions about IQ testing.

In sum, General Drummond is asking the Supreme Court to reverse a murder conviction and death sentence based on an interpretation of four words in one prosecutor's notes. But Drummond ignores the true facts of the case established by surrounding context.

Glossip also had the opportunity to reply to my interpreation of the notes. But, like Drummond, Glossip fails to engage on the key facts. Notably, Glossip never denies the critical point (discussed in my post yesterday) that on April 16, 2001, two women on his defense team interviewed Sneed. If so, it would appear that Glossip has an ethical obligation to tell the Supreme Court what information his defense team learned through that interview and related investigation. And yet one can read Glossip's brief without finding any discussion of his own defense team's interview of Sneed—an interview in which the defense team asked Sneed about lithium and Dr. Trumpet.

In his reply brief, Glossip briefly refers to my presentation of Smothermon's interpretation of her own notes. Glossip disparages her interpretation "as unsworn hearsay manufactured for an amicus brief." (Glossip Reply. at 5). But why hasn't Glossip (or General Drummond) asked her to explain her notes. Glossip briefly refers to the interview of Smothermon by Rex Duncan (discussed above). But it is apparently undisputed that, during that inconclusive three-minute interview, Smothermon asked to see her notes to interpret them, and Duncan replied there was "no need."

Glossip's team has also recently interviewed Ackley. But that interview apparently steered clear of the fact that Ackley was just memorializing Sneed's recounting defense team questioning. As with General Drummond, Glossip entirely ignores the fact that co-prosecutor Ackley's notes interlock with Smothermon's and make clear that Sneed was recounting being "visited by 2 women who said they rep[resented] Glossip"—i.e., what the defense team knew.

In addition, the Oklahoma Court of Criminal Appeals declined to order an evidentiary hearing on what the prosecutors' notes mean. In rejecting Glossip's claims, the OCCA held:

This Court has thoroughly examined Glossip's case from the initial direct appeal to this date. We have examined the trial transcripts, briefs, and every allegation Glossip has made since his conviction. Glossip has exhausted every avenue and we have found no legal or factual ground which would require relief in this case. Glossip's application for post-conviction relief is denied. We find, therefore, that neither an evidentiary hearing nor discovery is warranted in this case.

In his certiorari petition to the U.S. Supreme Court, Glossip declined to challenge the OCCA's decision not to order an evidentiary hearing. Of course, in any evidentiary hearing about the notes, Glossip would have to explain exactly what his defense team knew about Sneed before the trial—a subject that he has avoided discussing.

In sum, Glossip is asking the Supreme Court to overturn his death sentence based on a concocted interpretation of the prosecutors' notes that ignores their plain meaning. It is gobsmacking that he has gotten so far with so little. And, as a result of Glossip extending his frivolous litigation, the victim's family continues to wait for his sentence to be carried out … 10,128 days after Glossip commissioned the murder of Barry Van Treese.

In tomorrow's final post, I discuss how courts should handle non-adversarial litigation, such as this one—where Glossip and General Drummond are working hand-in-hand to keep the Supreme Court from learning the truth.

Editor's Note: We invite comments and request that they be civil and on-topic. We do not moderate or assume any responsibility for comments, which are owned by the readers who post them. Comments do not represent the views of Reason.com or Reason Foundation. We reserve the right to delete any comment for any reason at any time. Comments may only be edited within 5 minutes of posting. Report abuses.

Please to post comments

Will someone on the other side provide an answer to these posts?

Maybe Orin will get someone/respond. He got Steve Vladeck to respond to Blackman/Reed O’Connor.

I'm on neither side. I think the entire case shows what is wrong with the judicial system.

This guy Sneed admits to being the killer, but got his death sentence reduced to life without parole because he says Glossip hired him, and Glossip go the death sentence several times because the legal system found several procedural questions to salivate over instead of having to admit that convicting Glossip based mostly on a jailhouse snitch was pretty flimsy.

The only other evidence against Glossip is "coulda", because the widow says he was embezzling (I have seen nothing as to the validity of this) and that her husband was going to confront Glossip. So there's motive, and opportunity for setting it up with Sneed. Glossip says the meeting never happened. Far as I can tell, there is no evidence either way, so it still remains "coulda".

And as far as I know, there is no actual physical evidence tying Glossip to anything. But I haven't spent 25 years obsessing over this either.

I don't believe governments should execute any prisoners. It seems to me like the various prosecutors are hell-bent on this particular execution, which always raises my suspicions.

And there you have a non-partisan anti-government hack's opinion.

I'm personally not impressed with the reliability of testimony, where the witness gets compensated in some manner, either. And not getting the death penalty is one heck of a compensation.

I've seen a lot of that lately, where somebody got treated lightly when the law could have come down on them like a ton of bricks, in return for implicating whoever the prosecutor was really after. Michael Cohen getting off light in return for implicating Trump, for instance. It stinks on ice. I've got to admit it stinks on ice when it's testimony against somebody I've got no motive to defend, too.

I'm not saying entirely discount such testimony, but discount it at least somewhat, at least!

That said, the accounts I've read indicate that Glossip did some things to seriously cast suspicion on himself, such as sending the police off on wild goose chases.

I hadn't read about the wild goose chases.

What bothers me the most about jailhouse snitches getting reduced sentences is seeing some appeals where the defense was not allowed to bring up that tradeoff. Whether that is usual or rare, I do not know, but the jury certainly should know.

The prosecutor would be obligated under Brady to disclose that the witness had entered into such a plea agreement. (Which, of course, is not to say that all (most?) prosecutors are terribly fastidious about their Brady obligations.)

But they only had to tell the defense lawyers, right? I remember appeals precisely because the judge had forbidden the defense from bringing up the jailhouse snitch deals.

Perhaps so, but if the judge prevented the defense lawyer from inquiring into such arrangements to probe bias on the part of the witness, the appeal probably went in favor of the defense on that point (although it might have been declared harmless error or not preserved or some such).

"Harmless error" I suspect depends on the circuit - it's not too difficult to suppose that the 5th Circuit is more willing to accept a harmless error argument than, say, the 9th.

Really no one should be found guilty based on one witness without any corroborating evidence.

SGT:

Sneed worked for Glossip, was not a jailhouse snitch. Glossip changed his story, often, and drastically. Sneed has stuck to his story, that Glossip hired him, to commit the murder, all of which has survived 2 decades of appeals, because of many additional details, wherein judges are nearly eager to overturn such cases, which have a near 40% overturning rate, not because there is more error in such cases, but because judges give every benefit of the doubt, to the convicted.

"Shortly after assuming office in January 2023, and perhaps sensing political advantage, General Drummond ordered an investigation into Glossip's conviction by an allegedly "independent" investigator, Rex Duncan."

Political advantage *for a Republican AG in Oklahoma in blocking an execution*????

Hi Malika - An interesting point ... that I'll be discussing in Part III, tomorrow. The quick answer is yes.

Thanks, I look forward to it.

I wish people would stop referring to Attorneys General and Solicitors General as "General." See Herz, Michael Eric, Washington, Patton, Schwarzkopf, and . . . Ashcroft? (October 1, 2002). Cardozo Law School, Public Law Research Paper No. 55, Constitutional Commentary, vol. 19, page 663 (2002), Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=366920 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.366920

"As I pointed out yesterday, if the prosecutors' notes record what happened during a defense interview, obviously no Brady violation could exist. Because the prosecutors were simply recording what a state's witness recounted about questions asked of him by the defense team, the notes cannot contain information withheld from the defense."

I'm somewhat dissatisfied with this reasoning.

If the prosecutors had sat in on a defense interview, and taken their own notes, sure, they'd be under no obligation to share them with the defense. Let the defense take their own notes, nothing happened that the defense was unaware of.

OTOH, if the prosecutors, without the defense present, interview the defendant about what when on while the defense was interviewing the defendant? That's a completely different scenario. The defense have no way of knowing what the defendant said to the prosecution if they weren't present, and WOULD be entitled to the notes.

So, which was it: Did the prosecutors sit in on a defense interview and take their own notes, or did they later quiz the defendant ABOUT a defense interview, without the defense present during the quizzing?

It's a hugely significant difference, and I'm finding this account kind of vague about which happened.

Excellent question

The prosecutors later asked the witness (Sneed) if he had met with anyone. He said yes, he had met with two defense representatives (and investigator and an attorney) and then he (Sneed) recounted for the prosecutors the questions he had been asked by the two defense representatives.

In that case I'd say the defense actually was entitled to the notes. Doesn't necessarily amount to the sort of mistake that invalidates the conviction, but, yeah, they should have gotten them.

Just because he's talking to the prosecution about what he said to the defense, doesn't mean the defense knows everything he said to the prosecution.

It doesn't even mean he told the truth, or even remembered it as the defense remembered it.

Brett:

The horrendous issue is that the AG and Glossip won't interview the two prosecutors about what they meant, within their notes.

In the future, this may be known as a Drummond violation, whereby the state has decided to refuse to investigate their own charge, while appealing it to SCTUS.

Why? There’s no constitutional entitlement to discovery that isn’t exculpatory, and there’s nothing I see in Oklahoma’s criminal discovery rules that would seem to apply.

(To be clear: I think they should have disclosed the notes, and I support a discovery rule that would have required them to. But Oklahoma doesn’t have one, and failure to follow what I think are best practices isn’t a basis to reverse a murder conviction.)

If Sneed is repeating what he said to defense lawyers during a meeting at which they were not present, then the defense doesn't need the prosecutor's notes. Everything in the notes is information they were provided directly from Sneed.

"The parties' failure to respond confirms that their Brady claim is concocted and that they are forcing the victim's family to endure frivolous litigation. "

Ah, the cry of mentally ill cranks everywhere. "An important person didn't respond to my very important and somewhat unhinged missive, therefore conspiracy."

I mean to be sort of fair, at least he’s talking about an amicus brief on behalf of people with a stake in the matter, and not his posts. (Could totally see Blackman saying this about his posts).

But, there is zero obligation to respond to an amicus brief no matter who files them. It’s just as likely (if not more likely), that the parties didn’t think it was worth their time to engage with at all. They might have ignored it because they thought it was stupid and wrong, not because they thought it was so correct they had to ignore it.

One point to consider here (which I will discuss more tomorrow) is that ordinarily there are briefs on both sides of the question from the parties. But here, Glossip and Oklahoma are both on the same side - meaning amicus briefs defending the judgment below are more important than in a normal, adversarial case.

That is a fair point. Amici are especially important in cases where the prosecution and defense are, in effect, colluding.

I agree with all that, although it's worth noting that filing an amicus "on behalf of" is not the same as legal representation. There's no ethical obligations to a client. I suspect the prosecutor would be more amenable to communication from a legal representative of a family member than to someone who just got permission to slap a name on top of a brief.

I'll also reiterate that the letters read like the rambling manifestos of a crank but admittedly with better grammar. You just know from page 1 that any response that isn't complete capitulation is going to lead to endless, escalating replies without new substance.

But yes, my main point is that a lack of reply here doesn't "confirm" bad faith. It doesn't even suggest it. That would be bad enough if this weren't about a law school clinic brief, but I guess we're teaching young lawyers to baselessly impugn the character of "opposing" counsel if they feel at all slighted.

The pro-Glossip briefs take the position that the notes conclusively demonstrate that the witness was treated by a psychiatrist and the prosecutors knew about it. Prof. Cassell has, in my view, offered some pretty compelling reasons to doubt that. If there’s no response to his substance, I think it’s fair to start drawing some conclusions.

Why hasn't amicus asked the two prosecutors to provide affidavits or certifications setting forth their understandings of what their notes meant?

I provided an (thus-far-uncontested) letter from the two prosecutors, found in the appendix to my brief. Glossip also waived his right to seek an evidentiary hearing, since he has not sought review of the Oklahoma Court of Appeals' decision denying him an evidentiary hearing.

Prof. Cassell,

You have links to the same Smothermon email twice (I think you’re omitting the one that describes her first interview) and your link to the May 25 letter is broken.

Hi noscitur a sociis -

There is one email string - with the second conversation at the top, and then the first conversation at the bottom. So both emails are there and properly linked - but it is just a single "string" of two emails. More information is also found in the appendix to my amicus brief. Hope that helps.

Thanks, I missed that.

The link to the letter is still broken—specifically, the link is to “ believe%20that%20if%20you%20talk%20to%20the%20prosecutors%20who%20took%20the%20notes%20(Connie%20Smothermon%20and%20Gary%20Ackley),%20you%20will%20be%20able%20to%20quickly%20confirm%20that%20the%20notes%20recount%20what%20the%20defense%20knewâ%C2%80%C2%94not%20what%20prosecutors%20knew.” rather than whatever url you uploaded the letter to (although I see you included it in your brief).

The links are not broken. They work fine. Perhaps it is your browser.

But you presumably accept as valid a defendant's confession?

Or forfeiture/waiver of an issue by defense counsel?

No difference.

I don’t want to speak for Prof. Cassell, but I would be very surprised to discover that he thinks a defendant’s confession should be treated as conclusive and irrefutable evidence of guilt, or that he thinks there are no circumstances when waiver or forfeiture can be excused.

I have heard of rare cases where a judge rejected a guilty plea, on realizing the offense being prosecuted wasn't actually illegal. And the waiver sometimes gets excused if you can prove the guilty plea was coerced by prosecutorial misconduct. But it's pretty darned rare.