The Volokh Conspiracy

Mostly law professors | Sometimes contrarian | Often libertarian | Always independent

Trade, Public Opinion, and Political Ignorance

A new Cato Institute/YouGov survey finds contradictory attitudes on trade policy, and widespread ignorance. The survey also suggests a potentially promising political strategy for free trade advocates.

A new Cato Institute/YouGov survey sheds some interesting light on public attitudes towards international trade. It finds that most Americans seem to like international trade, but also that there are significant internal contradictions in their views, and that those views are often influenced by ignorance. Such results should not be surprising, given widespread public ignorance about a variety of other public policy issues. But they are nonetheless notable.

In some respects, the Cato surveys that the public is very supportive of free trade, despite recent trends towards protectionism in both major political parties. Some 53% have a favorable view of "free trade," compared to only 11% that have an unfavorable view. An impressive 63% say they favor "the United States increasing trade with other nations," while only 10% are opposed.

On the other hand, 62% favor "adding a tariff to blue jeans sold in the US that are manufactured in other countries to boost production and jobs in the American blue jean industry." Similarly, 62% favor reducing US tariffs "only if… other countries lower their trade restrictions on U.S. products because otherwise they will harm American businesses and jobs," and 15% oppose tariff reductions under all circumstances. Only 23% favor unilateral tariff reduction (the position held by most economists).

It looks as if large majorities favor "free trade" in principle, but shift positions when jobs are mentioned. But that latter view in turn dissipates once respondents learn that tariffs increase prices. Thus, the survey finds that 66% oppose imposing a tariff on blue jeans if it makes a pair of blue jeans $10 more expensive than it would be otherwise (58% would accept a more modest $5 increase in prices).

Given that almost all effective tariffs are likely to lead to significant price increases (otherwise, there would be no point in imposing them, since this is the only way they could meaningfully help domestic producers by diminishing purchases of foreign products), one would think this price-sensitivity would lead most people to oppose tariffs and support unilateral free trade. Tellingly, however, another question on the survey finds that only 38% know that free trade agreements reduce "the price of products Americans purchase at the store"; 39% believe (wrongly!) that trade agreements actually increase prices. A plurality also believe that trade agreements destroy more US jobs than they create. In reality, the opposite is true, and tariffs often destroy jobs by making production in the US more expensive. For example, Donald Trump's steel tariffs predictably led to job losses in industries that use steel as a production input.

The survey also finds that most Americans believe the trade deficit is harmful (a view overwhelmingly rejected by economists), and greatly overestimate the percentage of US imports that come from China (a view that sours opinions on trade generally, because most Americans view China with great suspicion). Interestingly, opinion about the trade deficit shifts when respondents learn the money paid for foreign goods is reinvested in the United States (as is overwhelmingly true, because Americans pay for the goods in dollars; thus, a trade deficit leads to a current-account surplus).

In sum, opinion on trade policy varies a lot depending on how questions are framed (depending on whether jobs or prices are mentioned). This is similar to public opinion on many other issues that most Americans don't know much about and don't necessarily have strong opinions on. The are similar contradictions and question-wording effects in public opinion on zoning and restrictions on housing construction.

Interestingly, the survey finds that only 1% of Americans consider trade to be one of the three most important policy issues for them (though for some, trade might be part of the broader issues of "jobs and the economy" and "inflation/prices," both of which rate among the most highly-rated issues in the survey). This low prioritization makes it even more likely that voters pay little attention to trade policy, and know little about it.

For free trade advocates, there is a major tactical takeaway: voters hate price increases, and will oppose tariffs if they think they cause such increases. The blue jean question is particularly telling - showing that most people won't tolerate modest price increases even if told doing so will increase jobs. The idea that tariffs increase prices is at least somewhat intuitive, and it may be possible to get it across even to relatively ignorant voters.

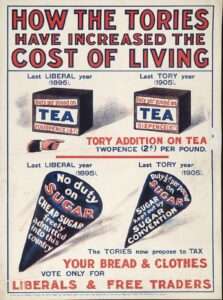

The idea of emphasizing the price-decreasing effects of free trade is far from a new one. It's how Richard Cobden, John Bright, and the British Anti-Corn Law League forged perhaps the most successful free trade movement in history, in nineteenth century Britain. After the repeal of the Corn Laws, the pro-free trade British Liberal Party successfully emphasized the issue of prices for decades to come.

The Cato/YouGov survey suggests modern free-trade advocates would do well to try the same strategy. Maybe we can learn a lesson from Cobden, Bright, and other old-time British Liberals.

Cato public opinion analyst Emily Ekins outlines the significance of some of the survey's other findings here.

NOTE: In addition to my primary position at George Mason University, I am also the Simon Chair in Constitutional Studies at the Cato Institute. However, I had no role in developing this survey.

UPDATE: Cato international trade scholar Scott Lincicome, who helped create the survey offers some insights on the results here.

Editor's Note: We invite comments and request that they be civil and on-topic. We do not moderate or assume any responsibility for comments, which are owned by the readers who post them. Comments do not represent the views of Reason.com or Reason Foundation. We reserve the right to delete any comment for any reason at any time. Comments may only be edited within 5 minutes of posting. Report abuses.

Please to post comments

thus, a trade deficit leads to a current-account surplus).

I think you mean a current account deficit leads to a capital account surplus.

There's a lot of ignorance here, but it's mostly on Ilya's part.

The truth is...it's complicated. In a perfect world, where all outside factors were held constant, free trade would make perfect sense. We however don't live in such a world. We live in a world with different countries, with different regulatory regimes, with different subsidies, bonuses, threats, potential shortages, and so on, that can lead to adverse outcomes.

Let's give a relatively simple example.

1. Assume for the sake of argument that China and the US can each produce steel for the same price, X$ a ton. In such a situation, the US has an advantage in the US market (as it doesn't need to pay transportation costs).

2. The US seeks to reduce carbon emissions, so it puts a tax on carbon emissions. Steel is an energy intensive industry, so such a tax raises its costs by $Y ton. Costs are now $X + $Y a ton.

3. China, by contrast, chooses not to put such a tax into place. Its steel production costs are still $X a ton. So long as transport costs are lower than $Y a ton, China can outcompete the US and undercut it.

4. This has the paradoxical effects of increasing global carbon emissions, as the US steel producers are put out of business, and the carbon cost of transporting steel to the US is added onto the currently inefficient Chinese industry. But...Free Trade?

---Again, a simple example. Different regulatory environments leading to a broken system. If China and the US were under the same regulatory environment (an ideal world)...free trade would work perfectly. But...they aren't.

You sound like those "tax justice" advocates, lamenting the fact that a country can't just raise its taxes on corporations and expect tax revenues to increase proportionately.

Or those who loathe ISDS arrangements, for similarly myopic reasons.

He's describing how things actually work, not what he thinks policy should be. The hypothetical US carbon tax could be any government imposition that increases costs: workplace health and safely laws, a minimum wage increase, corporate income tax, whatever. The relevant thing is that a government can impose costs on domestic products through a variety of mechanisms, but tariffs are the major way to impose analogous costs on foreign products.

He's making a theoretical argument, based on mercantilist concepts.

That's not how the real world works. One clue is how his hypothetical carbon tax puts American steel producers out of business. That's not even economics, it's just ideology.

I know it's hard for you to understand, but in a world where you have two regulatory regimes...one which puts an extra cost of production on a product, one that doesn't..

The one that doesn't put the extra cost on has an economic advantage.

That's simple economics.

That's less simple than simplistic. It echoes the punchline of a physics joke: ...but it only works with a spherical chicken in a vacuum.

In other words, your simple example works only because of its simple, non-real-world, one-factor example. Real-world international trade is never simple, and the always-present complex interplay of many, many economic factors usually dwarfs your simple production cost + bring-to-market cost = price knowledge of economics.

To the extent that economic nostrums are derived mathematically, they rely on an unstated principle: mathematical economics tells you how people would behave if people were numbers. The decision to believe that or not is more ideological than reasonable.

Indeed

So your argument is that bad regulations incentivize people to buy products from places without bad regulations? What exactly are you trying to prove? In your scenario, the people that are benefiting are the producers in the places with better regulations and consumers everywhere able to legally purchase those products. The incentives are aligned.

Only if you define a "bad" regulation as anything that increases production costs. (Which I don't).

What I'm trying to prove is "free trade" when there are different regulatory regimes is a misnomer. Failing to account for these differences is a mistake.

Let's give another example of how different regulatory environments affect free trade.

If a country is willing to enforce the law equally...it makes sense. But if a country unevenly enforces the law. Let's look at China again, in the context of a single company. Microsoft.

Microsoft products are wildly pirated in China. If China actually enforced the law there, billions of dollars would be heading back to the US. But...China chooses not to. So Microsoft (a US company) has billions in lost revenue. Is that "free trade"? Or a distortion of the market?

https://finance.yahoo.com/news/yes-chinese-piracy-lost-microsoft-123104842.html

Fans of hyper-rationalism in politics—mostly ideologues of one stripe or another—are naturally concerned about what they term, “political ignorance.” By that, they typically mean non-adherence to their preferred ideology.

That gets American constitutionalism wrong. It is not the reason of the jointly sovereign People which is supposed to constrain politics, and thus government. It is the People’s will, exercised at pleasure. The role that reason ought to play, and the extent reason should be heeded, remain among the questions the people get to decide at their pleasure, and without constraint.

Ideologues will always remain free to try to persuade the People that the ideologues’ preferred rationalisms ought to guide policy. That can never be properly understood to mean that one species of rationalism or another ought to provide legitimate basis to decide case outcomes in courts.

Those inclined to suppose courts are already operated without regard for ideology ought to reflect that among the ideologies the People remain free to ignore is the entire corpus of American economic rationalism. Nothing in American constitutionalism decrees a free market economy, a democratically socialist economy, a communist economy, or any other species of rationalist approach to government.

The People remain free to experiment at will, chaotically, in ignorance, if that be their pleasure. The law should not attempt to say otherwise.

The People have delegated their legislative power...

SRG2 — Do you intend that as an assertion that courts comprised of judges sworn to uphold the Constitution owe their sworn allegiance to the government, and not to the People?

Have you bothered to read the text of the oaths they took? Doing so would answer your question.

So Nieporent, your answer is that the oath is an oath to uphold the government.

On that basis, what happens to the idea of a government of limited powers? An official sworn not to disagree with government is not even slightly a bulwark against government abuse.

Where does power to protect individual rights come from, except paradoxically from the government which is violating the rights?

Perhaps you would say instead, but the oath is to the Constitution, not to the government. That remains an evasion. Because you insist for the government sole power to interpret the Constitution. As founder James Wilson wrote explicitly, that approach takes you a step in the direction of the truth, but does not reach it. It leaves you among those Wilson characterized as those with insufficient understanding of our systems of government.

I get that as a libertarian you remain rationalistically committed to evade all such questions, because they tend toward answers based on sovereignty—which was defined in the founding era as absolute, uncontrollable, and unappealable power, exercised at pleasure, and without constraint—as shocking a notion as any libertarian ever encountered.

But it has its uses. American constitutionalism, for instance, is founded upon that notion. That is an undeniable historical truth, and like most committed libertarians, you hate it—hate it without even noticing how well it has worked in practice. (That lack of notice is a price folks pay for heedlessness about history, but I will not dwell on that now.)

Too bad for libertarians. Until libertarians get used to endorsing that notion they hate so much, they will remain cranks without answers even to questions about where their own critiques of government come from.

Natural rights? The ones vindicated by God? Really? That remains a pre-Enlightenment notion which worked pretty well, while everyone, including kings purporting to rule by divine right quailed in the face of the power of the Catholic Church. Alas, that quailing ended before the assertions of divine right did, with results too many Kings’ subjects paid a price for, as Hobbes set forth in, Leviathan. Hobbes merely noted what the subjects had already experienced. Hobbes purported to do no more than notice, but he was especially good at it.

Divine right does not work at all anymore. Why not? Because the idea of joint popular sovereignty, invented during the American founding, replaced divine right with something which works far better—the notion of joint popular sovereignty. But libertarians like you hate that idea, no matter how well it has worked. You know why? Because like adolescents everywhere, deep down you long to be such a divine-right king yourself, free to govern as you please, without even constraint by the Church.

And unlike most adults, aging libertarians like you never got over that longing. More than two centuries after the American founding showed the world a better way, libertarians still long to be kings. You ought to reflect on that.

I mean, that has nothing whatsoever to do with the post. I'm surprised you didn't throw in a rant about § 230 while you were at it.