The Volokh Conspiracy

Mostly law professors | Sometimes contrarian | Often libertarian | Always independent

Notes on "The Restrained Roberts Court"

Contrary to popular perception, the current Supreme Court overturns precedent and declares laws to be unconstitutional less often than its predecessors did.

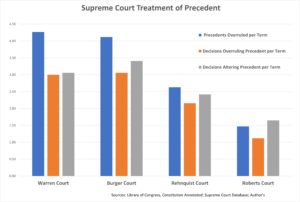

In the July 31 issue of National Review, in an article titled "The Restrained Roberts Court," I explain why some common criticisms of the current Supreme Court are simply untrue. In particular, I explain that the Roberts Court overturns precedent and holds legislative enactments unconstitutional significantly less often than did the Warren, Burger, or Rehnquist Courts. In other words, the Roberts Court is meaningfully less "activist" than its post-WWII predecessors, at least as measured by conventional metrics.

From the article:

Commentators and reporters generally accept that the current Court is more likely to overturn precedent and invalidate laws than we have come to expect. Yet this widely shared perception is wrong. Based on available metrics, the current Court is less likely than its predecessors to overturn precedents or invalidate legislative enactments. If such actions are the hallmark of judicial imperialism, the Roberts Court is not particularly imperialist. . . .

the Roberts Court is the least likely of any court since World War II to overturn precedent. The Warren, Burger, and Rehnquist Courts all overturned Supreme Court precedents at a higher rate than the Roberts Court, and it is not particularly close. Compared with its predecessors, the Court under Chief Justice Roberts has largely maintained the status quo.

This is not anything new. Folks have been charging that the Supreme Court under Chief Justice Roberts has been abandoning precedent for years. As I have shown in prior posts going back years, the data did not support such charges then, and it does not support such charges now.

| Terms | Cases Overruled | Overruled/Term | Overruling Cases | Overruling/Term | Alteration/Term (SCD) | |

| Warren Court | 15 | 64 | 4.27 | 45 | 3.00 | 3.06 |

| Burger Court | 17 | 70 | 4.12 | 52 | 3.06 | 3.41 |

| Rehnquist Court | 19 | 50 | 2.63 | 41 | 2.16 | 2.42 |

| Roberts Court | 17 | 25 | 1.47 | 19 | 1.12 | 1.65 |

While it may well be the case that the current Court, over time, may begin overturning precedents at a higher rate than its post-WWII predecessors, we have not seen that yet (and that is true whether one treats the Roberts Court as a single court, or if we divide it into a "First" and "Second" Roberts Court with the change occurring either when Justice Kavanaugh replaced Justice Kennedy or Justice Barrett replaced Justice Ginsburg.)

As in my prior analyses, I based my claims looking at three data sets, two compiled by the Library of Congress (precedents overturned per term and decisions overturning precedent per term) and one from the Supreme Court database (precedents altered per term). All three data sets produce similar results.

The number of precedents overturned per term may be lower in the Roberts Court, but are the precedents overturned more longstanding or significant? It does not appear they are any older or more longstanding. The average age of precedents overturned by the Roberts Court (38 years old) is older than that of the Warren Court (22 years old), but comparable to that of the Burger (35) and Rehnquist (39) Courts.

What about significance? From the article:

It is fair to note that not all cases — nor all precedents — are created equal, and some observers have considered the precedents that the Roberts Court has overturned to be especially important. But there is no neutral measure of a precedent's importance. Most people likely think the Dobbs decision to overturn Roe v. Wade was more important than the overturning of Nevada v. Hall's holding on state sovereign immunity in Franchise Tax Board of California v. Hyatt. But was Dobbs more significant than the Court's 2002 decision in Atkins v. Virginia to overrule Penry v. Lynaugh and declare the execution of an intellectually disabled person to be a violation of the Eighth Amendment? And if so, by how much? And what about decisions that overturned precedents concerning the rights of criminal defendants to confront their accusers, or the authority of states to tax out-of-state businesses, or the application of the 14th Amendment's liberty and equality guarantees to homosexual conduct and gay marriage?

The article shows how there is a similar story to be told when it comes to Court decisions declaring legislative enactments to be unconstitutional. The Roberts Court is doing that less than its post-WWII predecessors as well.

Note that these trends coincide with the Court hearing fewer cases, and this is largely due to the justices' collective decision to hear fewer cases. Hearing fewer cases means there are fewer opportunities to overturn precedent, declare statutes unconstitutional, or otherwise shift the law. The cases which produce such outcomes may be a larger share of the Court's overall decisions, and such cases may have a more consistent ideological valence than before, but as a quantitative matter, the Court is still doing less.

One claim about the Roberts Court that I think has greater merit is that it has is more skeptical of the executive branch than its predecessors have been. I think this is a fair claim, and is the result of a longer term trend. Across the board the Court has become less deferential to the executive branch over time. This is true in the context of administrative law (going from, say, SEC v. Chenery II to West Virginia v. EPA) but in areas like national security as well (going from Ex parte Quirin to Boumediene v. Bush).

What is most different about the Roberts Court is not that it is more likely to overturn precedent or declare statutes to be unconstitutional. What is different is that it is a more consistently conservative court than its predecessors. The Burger Court had a supermajority of justices appointed by Republican presidents, but was not particularly conservative. While the Rehnquist Court was thought by some to be fairly conservative, it issued plenty of decisions overturning precedents or declaring statutes to be unconstitutional that most would consider to be "liberal" decisions. Lawrence v. Texas and Roper v. Simmons are good examples.

During the first twelve years of the Roberts Court, the Court tended to be conservative, but not consistently, and certainly not consistently in cases in which precedents were reconsidered or statutes held unlawful. Justice Kennedy was the median justice during this period and the Court's decisions to overturn precedents and reject statutes largely tracked his particular jurisprudential vision, and this often meant decisions overturning precedents or rejecting statutes while moving the law in a "liberal" direction. Obergefell v. Hodges and Kennedy v. Louisiana are good examples.

When Justice Kennedy was on the Court, he was the median justice on a Court that was otherwise 4-4. This meant that his preferences often controlled. Chief Justice Roberts and Justice Kavanaugh may be the median justices on the current court, but both of them are more consistently conservative in their rulings than was Justice Kennedy. Further, for the Court to overturn precedent or reject a statute on "liberal" grounds, the concurrence of more than one conservative justice is required. So we may get an occasional decision in which, say, Justice Gorsuch and Justice Barrett join the three progressive justices to overturn a conservative precedent, but such cases are likely to be rare.

This change in the court affects what cases the Court agrees to hear as well. It takes four justice to grant certiorari, so the three progressive justices lack the ability to force the Court to hear a case that concerns them (and they may not want to force the consideration of such cases either, as they may not like the outcome). This only reinforces the likelihood that when the Court decides to reconsider a prior precedent, it is more likely to reconsider a precedent about which the conservative justices are skeptical, and any resulting decision will likely move the law in what most would consider to be a conservative direction.

My National Review article concludes:

The reality is that some precedents should be overturned and some federal or state laws should be declared unconstitutional. It is also the case that the nation is divided over when such steps are warranted. I approve some of the Roberts Court's decisions in each of those categories and disapprove of others — but, in each case, my evaluation is based on my sense of the merits of the case and the Court's arguments. Accusations that the Court is vaporizing precedent and trampling democratic enactments — suggesting that it is not merely making bad decisions but doing so in an illegitimate way — are part of a broader effort to delegitimize it.

For many decades and with some regularity, the Court has overturned precedents and struck down legislative enactments. But so long as most such decisions moved the law in a progressive direction, legal elites mostly bit their tongues. What is different about the Roberts Court is not that it is keener to change the law but that, when it does so, it is more likely to shift doctrine in a conservative direction. If that makes the Court "not normal," as President Biden recently charged, and if that is supposed to be a problem, then the Court's critics should make their case openly and honestly.

Editor's Note: We invite comments and request that they be civil and on-topic. We do not moderate or assume any responsibility for comments, which are owned by the readers who post them. Comments do not represent the views of Reason.com or Reason Foundation. We reserve the right to delete any comment for any reason at any time. Comments may only be edited within 5 minutes of posting. Report abuses.

Please to post comments

When you lose on the facts, complain about the "legitimacy" of the process. It's human nature, I'm afraid. We really aren't a very honest and trustworthy breed, are we?

Regarding how the press in particular reports on this kind of thing, I look to how weather patterns are reported as my guide. When we are in an El Nino pattern and temperatures are naturally elevated, we hear all about global warming. When we are in the La Nina pattern and the temperatures are reversed, we hear nothing.

Likewise with the Supreme Court. When the administrative state loses a case, we hear all about how abnormal the Court is. When they win, we hear nothing.

Still have not overruled the case that is killing America. Griggs v. Duke Power, which unleashed the disparate impact virus, which is killing our Republic, a Republic that, like all repblics, can only stand as a meritocracy. California just passed a bill for disparate impact analysis for sentencing of convicted felons. If you are white, your sentence is higher, if you are black, get out of jail free. Griggs violates the Equal Protection Clause.

You should look into the difference between a bill and a law.

Is the ghost of Patrick Henry as bigoted and reprehensible as Patrick Henry -- a silver-spooned hypocrite, a superstition-addled slaver, and lifelong selfish asshole -- was?

I'm not a fan of disparate impact theory as a general rule, but overruling Griggs would be moot since it's been codified by Congress. And does not violate the Equal Protection Clause (for multiple reasons, including that the 14th amendment does not apply to the Supreme Court.)

And, no, California did not do anything like what you said.

While Griggs came up with a concept ripe for misuse it in itself wasn't so bad: Disparate Impact is discriminatory where there is no relation between the factor causing the disparate impact and the legitimate aims of the organization.

In that case a high school diploma to be a janitor at a power plant.

But you apply it to cases like the one in New York where over a billion is being paid out to minorities that couldn't pass the teachers exam just boggles the mind. I am assuming that the test was crafted and good faith, but I can't imagine the NY city schools set out to exclude minorities from '94 to 2014.

https://nypost.com/2023/07/15/nyc-bias-suit-black-hispanic-teachers-and-ex-teachers-rich/

in each case, my evaluation is based on my sense of the merits of the case and the Court's arguments.

Awesome. Your opinion is noted. Dressing it up with some bar charts you admit are not useful does not change that this is all it is.

The legal argument I've seen is somewhat more objective, though still with plenty of opinion left. But it is procedural, not substantive.

The argument is that the Court is reaching down and finding cases well before it needs to when it has a political hobby horse, is throwing justiciability questions catiwampus to get to the place it wants to get, and then goes for to.

So whether you like the precedent or not becomes secondary. Seems that's a better thing to address rather than if Prof. Adler is into the opinion or not.

The significance of Dobbs dwarfs every other case named in the number of Americans impacted. (And Clarence Thomas has a whole list of rights that must be struck down if the reasoning in Dobbs is correct.) No mention of the huge shift in privileging religious rights, whether specific cases were officially overruled or not. The long string of partisan decisions to promote Republican prospects, also ignored.

"The significance of Dobbs dwarfs every other case named in the number of Americans impacted. "

What's you basis for that, other than you don't like Dobbs? If you include the Warren, Burger and Rehnquist courts, there are lots of decisions that affect more Americans than Dobbs.

Comparison to the cases named, as I stated; Dobbs affected lots more people than the cases described.

Franchise Tax Board of California v. Hyatt - how often do people sue states in another state's courts? Whose life would be changed whichever way that came out?

Atkins v. Virginia - there are not very many executions, let alone ones where this might come up. Sure, many people oppose or support capital punishment on principle, but relatively few will be directly affected by a given execution (the person executed, people close to that person, people who were victims of that person's crime or close to such victims).

"the rights of criminal defendants to confront their accusers, or the authority of states to tax out-of-state businesses" - you think these are totally going to change people's lives and the outcomes of elections nationwide.

"the application of the 14th Amendment's liberty and equality guarantees to homosexual conduct and gay marriage" - getting warmer, but relatively few people are directly affected by these, no matter how worked up non-gays get; the Republican party used it as a wedge issue for a while, until it stopped working, and even at the time it looked more like people who were upset that the Ghostbusters movie was remade with women, thus retroactively destroying their childhoods. And that's a decision that expanded rights rather than taking away a longstanding constitutional right, complete with a hit list of rights that Clarence Thomas would dispense with (conspicuously excluding Loving, of course).

Even for those who agree with the Dobbs decision, they should recognize that it swung the red wave to almost nothing (like McCarthy's T-shirt says, "The nation had high inflation and an unpopular Democratic president and all I got was this T-shirt and a slim unmanageable House majority, mostly from past gerrymandering") and probably portends SCOTUS expansion.

This doesn't strike me as a fair reading of his article. The data he presents is largely objective - rates of overruling precedent over time, etc. He correctly points out that the "imperial court" criticisms are unfounded but concedes there is a trend toward increasing constraints on the executive branch. Then, at the very end, he notes that he has agreed with the court's overruling of precedent only some of the time. In context, the quote you excerpted makes this pretty clear:

"I approve some of the Roberts Court's decisions in each of those categories and disapprove of others — but, in each case, my evaluation is based on my sense of the merits of the case and the Court's arguments."

This isn't a qualifier covering the whole analysis but a concession that, regardless of the overall numbers, reasonable people can disagree whether this or that precedent should have been overruled.

As for the contention that the court is reaching out for cases to overrule precedent, if that were so, one would expect it to show up in the numbers. Given that the court takes fewer cases overall, a pattern of reaching for cases to overrule should be easily discernible in the data. There is no such pattern.

Hey, nice comment!

It looks to me like the article does some quantitative work, but then discards it, saying "It is fair to note that not all cases — nor all precedents — are created equal, and some observers have considered the precedents that the Roberts Court has overturned to be especially important."

I think that's right, and that is the common challenge of political science. But then why bother faffing about with those bar charts at all??

The argument is that the Court is reaching down and finding cases well before it needs to when it has a political hobby horse, is throwing justiciability questions catiwampus to get to the place it wants to get, and then goes for to.

For anyone who has a read histories/biographies of the Warren Court and its justices, that is pretty much how it operating. The chief sent his law clerks looking for cases which could change the law.

Not sure whether you’re suggesting this is only recent behavior of this arch-conservative court trying to turn back the clock. Every precedent is precious, when it’s one I like.

I think that is a fair criticism of the Warren Court (though the law clerks story is new to me).

But that doesn't mean it's not a fair criticism of the Roberts Court as well.

So what cases overturning precedent do you think they reached for?

Maybe Obergefell, but I can't think of any others, not Dobbs, abortion cases have been regulars on the docket for decades.

Sounds like one of those "Its not what you said, its how you said it." Arguments, its almost always what you said, how you said it is the excuse to complain about it.

Evidence? Truth? No one cares about those petty things anymore. All we need to know is the narrative.

The Roberts Court also abandons or narrows precedents without overturning them — with little restraint even though it is a break with the past.

That seems an important point.

This is a good point - the decisions the Roberts Court makes have a decent proportion that just ignore precedent and proceed tabula rasa.

Dobbs does this.

On the one hand, this makes for weaker, more easily overturned decisions. On the other, it adds chaos to a bad decision which just makes things worse in the short to medium term.

But what it is is extremely unrestrained.

Dobbs is consistent with Jacobson v. Massachusetts and Buck v. Bell.

It explicitly ignores all previous precedent on abortion without even engaging it.

...Did you just cite Buck v. Bell as a foundational precedent?

Buck v Bell....sound law. Cited during the pandemic multiple times.

What was it Holmes said, three generations of imbeciles is enough? Could have been talking about Congress. 🙂

Josh Blackman emphasized this yesterday: "A hallmark of the Chief Justice's jurisprudence is to not formally overrule cases, but to read them in such a way as they are effectively overruled." https://reason.com/volokh/2023/07/31/justice-alitos-interview-in-the-wall-street-journal

Its interesting that of the Big 5 Roberts Court cases, Heller, NFIB, Dobbs, Obergefell, Brian just 2 were overruling precedent. Obergefell made progressives wildly happy, and enraged conservatives, Dobbs the opposite. NFIB was a mixed bag, we dodged the mandate bullet, but lost on everything else. And the two big gun cases didn't overrule any precedent, it merely reversed half a century of refusing to say what the constitution required letting states, the feds, run roughshod over the 2nd.

You might have a different view of the Big 5, for instance Citizens United was big in its day, but I think few people care anymore.