The Volokh Conspiracy

Mostly law professors | Sometimes contrarian | Often libertarian | Always independent

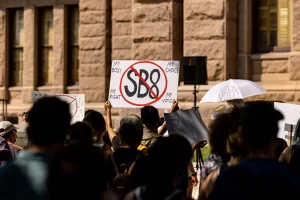

The Legal Battle Over Texas SB 8 is Far From Over

Opponents of this dangerous law have a variety of options left to pursue in state and federal courts, despite their recent defeat in the Texas Supreme Court.

On Friday, the Texas Supreme Court ruled that state medical licensing authorities have no authority to enforce Texas SB 8 - the controversial state law banning nearly all abortions six weeks or more after conception. Some defenders of SB 8, such as co-blogger Josh Blackman, claim this will put an end to lawsuits challenging the constitutionality of the law. But such triumphalism is premature.

The key issue at stake in the SB 8 litigation is whether Texas can evade judicial review by limiting enforcement authority exclusively to private parties (see here and here for more detailed explanation). SB 8 seemingly bars enforcement by state officials, and instead delegates it to private litigants, who each stand to gain $10,000 or more in damages every time they prevail in a lawsuit against anyone who violates the law's provisions.

If the SB 8 ploy succeeds, it would provide a roadmap for undermining other constitutional rights by delegating enforcement to private parties. Preenforcement lawsuits against laws attacking such rights would be barred. And the possibility of enormous civil liability would chill the exercise of the rights in question, even if there were some chance of ultimate vindication through defensive litigation.

As Texas' solicitor general admitted in the Supreme Court oral argument, there is no limit to the amount of liability a state could impose on violators. If $10,000 isn't enough to create a chilling effect, the state could increase the damages to $1 million or even more. A number of other states have already begun to imitate Texas' strategy, as with California's plan to use it to attack gun rights.

In Whole Woman's Health v. Jackson, decided in December, the Supreme Court ruled that abortion providers challenging SB 8 are not allowed to sue the Attorney General of Texas, state judges, state court clerks, and the one private individual who was a defendant in the case. But eight of nine justices agreed the plaintiffs could potentially sue state medical licensing officials, because the latter had the authority to enforce SB 8 by denying licenses to practitioners who "violate the terms of Texas's Health and Safety Code, including S. B. 8." But, as Justice Neil Gorsuch noted in his opinion for the Court, the issue of whether the licensing officials had such power is ultimately a matter of Texas state law.

On remand the US Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit certified that state law question to the Texas Supreme Court, which has now concluded the licensing officials have no authority to enforce SB 8 either "directly or indirectly." It does not follow, however, that there are no other state officials that plaintiffs can sue. As I have previously pointed out, Gorsuch's reasoning may well permit lawsuits against state officials tasked with enforcing state court judgments, such as sheriffs. Such people are not judges, and therefore not subject to the Supreme Court's precedents limiting injunctions against state court proceedings. There may be other nonjudicial state officials involved in the enforcement of judgments, as well.

Opponents of SB 8 would do well to search out all such potential defendants, and file cases against all of them. At least two of the justices who joined Gorsuch's opinion expressed grave concerns, in oral argument, about the threat SB 8 poses to constitutional rights (Kavanaugh and Barrett). Only one of the "Gorsuch four" needs to switch in order to defeat the SB 8 ploy in a future case. The three liberal justices and Chief Justice John Roberts have already indicated (in their opinions in the December ruling) that they are open to allowing lawsuits against state court clerks.

I am far from infallible when it comes to such predictions. But I think there's a strong likelihood that at least one of the four will indeed switch, if faced with a choice between modestly weakening the abstention and sovereign immunity doctrines underpinning SB 8, and imperiling judicial protection for a wide range of constitutional rights - and in the process significantly weakening the power of judicial review.

For reasons I highlighted here and here, rights valued by conservatives are threatened along with those valued by liberals. California's plan to target gun rights reinforces that point. Future litigation on SB 8 - and perhaps other state laws inspired by it - will reveal whether the Supreme Court (and lower federal courts) are willing to address the threat.

In the meantime, we should not forget that a Texas state court ruled in December that SB 8's delegation of enforcement to private parties violates the Texas Constitution. That ruling is now on appeal, and the trial court did not issue a injunction against enforcement of SB 8 while litigation continues. Nonetheless, it is entirely possible that SB 8's private enforcement ploy will ultimately be defeated in state court.

A state-constitutional ruling against SB 8 cannot prevent other states from imitating the statute. Those states' constitutions may not constrain enforcement delegation in the same way. But a Texas state ruling against SB 8 might at least have some persuasive value for other state courts. At the very least, state constitutional challenges are an additional tool in the armory of those who seek to counter this pernicious strategy for undermining constitutional rights.

As I have emphasized before, the fight over SB 8 is not primarily about abortion. Even if you believe the Supreme Court should overrule or limit Roe v. Wade and other precedents protecting abortion rights (which it may soon do in the Dobbs case), you have reason to be concerned about this menace to our other constitutional rights.

In sum, the legal battle over SB 8 and its would-be imitations elsewhere is far from over. Opponents should not give up too easily.

Show Comments (128)