The Volokh Conspiracy

Mostly law professors | Sometimes contrarian | Often libertarian | Always independent

Lakefront and the Public Trust Doctrine Today: A Litigation Roulette Wheel

Success via the doctrine depends more on somehow securing federal jurisdiction, at least briefly, and on judges’ docket-management decisions than on any remotely predictable criteria.

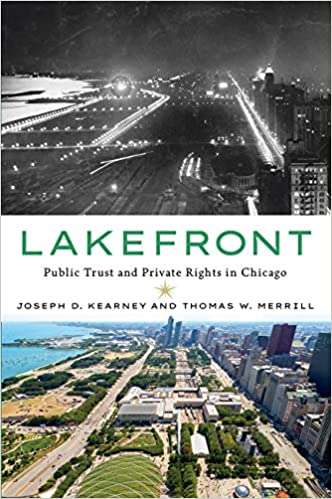

The transformation of the public trust doctrine in Paepcke v. Public Building Commission in 1970, described in the fourth entry of this five-post guest series and at greater length in our new book, Lakefront: Public Trust and Private Rights in Chicago (Cornell University Press), soon bore fruit in terms of the first (and only) invalidation by the Illinois Supreme Court of a legislatively authorized project involving landfilling of Lake Michigan.

The story involved U.S. Steel's South Works: In 1963, the legislature authorized U.S. Steel to fill an additional 194.6 acres in the lake for the steel plant's expansion on the far South Side of Chicago. The Illinois Supreme Court rejected one challenge to the plan in 1966. But for reasons that are unclear, the corporation waited until 1973 to tender the modest sum of money ($100 per acre) needed to take title to the submerged land. In the meantime, the political winds had shifted.

The attorney general in the early 1970s, William Scott, was busy nurturing a reputation as a champion of the environment, which he hoped to parlay into the Republican nomination for a U.S. Senate seat (both political parties sought to capture the environmental vote back then). Suing on behalf of the people, he asked the courts to block the sale of submerged land to U.S. Steel as a violation of the public trust doctrine.

In 1976, in People ex rel. Scott v. Chicago Park District, the Illinois Supreme Court ruled against the project. Citing and quoting Professor Sax as in Paepcke, the court suggested that the public trust doctrine prevents any conveyance of public lands for private purposes. It acknowledged that the legislature had made express findings that the conveyance in question would turn "otherwise useless and unproductive submerged land into an important commercial development to the benefit of the people." But it rejected "[t]he claimed benefit [of] additional employment and economic improvement" as "too indirect, intangible and elusive to satisfy the requirement of a public purpose."

Factually, the Scott case was closer to the original (1892) Illinois Central case than to Paepcke. The proposal involved a plan to fill a large amount of open water for the benefit of a private corporation, not the transfer of a chunk of inland park to construct a public school. Thus, the Scott decision did little to clarify what resources are covered by the public trust, or what is meant by a private, as opposed to a public, purpose for a transfer. It did suggest, however, that the broad deference to the legislature, which characterized the decisions before Paepcke, had been replaced by something closer to strict scrutiny.

The aggressive stance reflected in Scott was soon emulated by a federal district court in a decision that provides an ironic juxtaposition to the Northwestern campus expansion in the early 1960s. In the late 1980s, Loyola University, on the North Side of Chicago and barely four miles south of Northwestern, was effectively blocked from expanding into the surrounding neighborhood, just as Northwestern had been in Evanston. Like Northwestern, it concluded that its best option was to fill a portion of the lake to the east.

Loyola's plan was much more modest than Northwestern's; included public access and uses; and, unlike Northwestern's, underwent a rigorous environmental review that resulted in modifications designed to satisfy a variety of federal and state environmental agencies. Everyone from local politicians to community groups to the state legislature to agencies of the federal government signed off.

But Loyola's plan was contested by an environmental group that got into federal court based on its challenge to the federally mandated environmental review and that raised the public trust doctrine as a matter of what is now called supplemental jurisdiction. The federal court ignored the federal challenge; extrapolating from Paepcke and Scott, it held that the project violated the state law public trust doctrine. Loyola soon announced that the funds it had set aside for the project had been exhausted by consulting and legal fees, and decided not to appeal, despite the district judge's curious exhortation that it should do so.

Subsequent decisions can only be described as a mixed bag. In Friends of the Parks v. Chicago Park District (2003), the Illinois Supreme Court upheld a remake of the venerable Soldier Field designed to retain the Chicago Bears as principal tenant of the stadium. Although accommodating the wishes of a professional football team might seem to be a "private purpose," the court stressed that the park district would remain "the owner" of the stadium and hence would retain significant "control" over the use of the facility. The court assumed without discussion that the public trust applies to the stadium, built on landfill in 1924 by a predecessor of today's park district.

The two most recent decisions, both in federal court, came in citizen suits challenging nonprofit foundations that wanted to build museums on the lakefront honoring the accomplishments of notable individuals.

The first involved a proposal to build the Lucas Museum of the Narrative Arts, to be paid for and operated by a foundation established by the filmmaker George Lucas and to display (among other things) props from his Star Wars films. Although the city establishment was enthusiastic about the proposal, envisioning additional jobs for the economically distressed South Side and more tourist traffic, the Friends of the Parks did not like the design or the self-referential aspect of the project. The group managed to get the matter into federal court on a dubious theory of federal jurisdiction and to tie it up there. In 2016, George Lucas got disgusted with all the delay and announced that he would build his museum in Los Angeles (opening is projected for 2023).

The second involves the Obama Presidential Center (OPC), a museum honoring the nation's first African-American president and sometime Chicago resident. The facility will include a digitalized version of what was once called a presidential library. Chicago won the competition to be the site of the OPC, to general acclaim. The only disagreement was whether the OPC should be located in Jackson Park, on the lakefront, or farther west, in and along Washington Park.

A group calling itself Protect Our Parks sued in federal court to block the use of the Jackson Park site as violating the public trust doctrine. This was rejected by Judge John Robert Blakey on the ground that the site in question had never been submerged land, and that the relevant precedent (Paepcke) only required express legislative authorization, which had been secured. The decision was vacated on appeal, in an August 2020 opinion by then-Judge Amy Coney Barrett, on the ground that the plaintiffs had failed to plead injury in fact, as required to establish federal court jurisdiction. The group is now back in the district court, with a new lawsuit, arguing that the federal review of environmental impacts was inadequate. It also raises the public trust question anew, based on supplemental jurisdiction.

Collectively, the post-Paepcke decisions suggest that the public trust doctrine has become a kind of roulette wheel in determining whether particular development can move forward on the Chicago lakefront. It is unpredictable whether advocacy groups will sue to enforce the doctrine. It is unpredictable how the courts will respond. The Lucas Museum case and the Loyola case show that one need not secure a final judgment in order to affect the outcome. Rulings by trial courts refusing to dismiss a case can impose enough delay to cause the cancellation of projects. These concerns are magnified if the matter is litigated before a single federal judge insulated from the ordinary political process.

This is not what Professor Joseph Sax envisioned when he advocated an expanded use of the public trust doctrine to allow broader public participation in decisions to transfer public resources to private entities. And where federal permits are needed, a participatory process may be required by the National Environmental Policy Act. States are free to mandate a similar process when state and local parks, wilderness areas, or other state-owned natural resources are proposed to be privatized in some fashion. Explicit approval by the state legislature, consistently required by the Illinois public trust doctrine for 125 years, is another good idea. This assures that a broadly representative body, the state legislature, takes a close look at a project before it is finally approved. But asking a court, often a single federal judge, to decide whether the nebulous public trust has been violated, serves only to defeat the popular will on what amounts to a random basis.

[* * *]

This is our fifth and final guest post (previous entries can be found here, here, here, and here). Great thanks to Eugene Volokh, Jonathan Adler, and the other members of Volokh Conspiracy for this privilege. See you at other blogs later this summer—and perhaps at the Lakefront.

Show Comments (2)