The Volokh Conspiracy

Mostly law professors | Sometimes contrarian | Often libertarian | Always independent

Lakefront and the Public Trust Doctrine—Enter Professor Sax

In 1970, the public trust doctrine got new life, simultaneously with a larger environmental revolution.

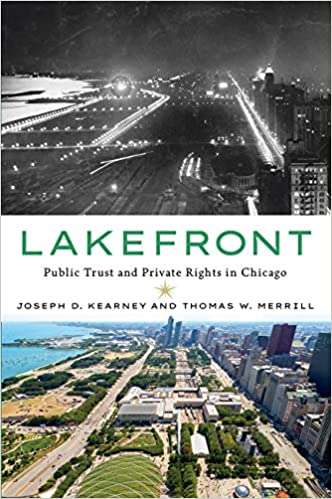

Our first and second posts in this guest series described not only the U.S. Supreme Court's unexpected announcement of the public trust doctrine in the 1892 Illinois Central decision but also the subsequent determinations by the Illinois Supreme Court that the state legislature was the trustee of the public trust and that the judiciary would defer to the trustee's decisions. With this latter set of determinations, the public trust doctrine effectively became little more than a requirement that the legislature authorize any project entailing landfilling in Lake Michigan. As we recount in our new book, Lakefront: Public Trust and Private Rights in Chicago (Cornell University Press), this understanding of the trust prevailed for the next 75 years.

Then, in 1970, the Illinois Supreme Court abruptly changed direction. Relying on a new law review article by Professor Joseph L. Sax, of the University of Michigan Law School, the court reformed and invigorated the public trust doctrine, even if the precepts were scarcely clearer than they had been when the doctrine emerged from the U.S. Supreme Court in 1892.

The understanding that the public trust doctrine required little more than legislative approval was dramatically illustrated by an episode that occurred in the early years of the twentieth century. A large steel mill owned by the U.S. Steel Corporation, known as the South Works, was discovered to have augmented the size of its holdings by dumping slag into Lake Michigan, on the far South Side of Chicago. After litigation between the company and local authorities (which wanted to recover property taxes on the filled land), the state legislature in 1909 resolved the issue by granting the company 234 acres of submerged land—more than enough to ratify the illegal fill. The state attorney general, in a superficial analysis, assured the governor that he could sign the bill without any concern that the grant violated the public trust identified in the Illinois Central decision.

The following decades would see landfilling up and down the lakefront, all authorized by the legislature. Perhaps most consequentially, park districts on the North and South Sides of the city (later merged into a single Chicago Park District) were given authority by the legislature to fill the lake along the shore so as to construct a system of parks and, as part of the construction, to extend Lake Shore Drive farther north and south.

In order to buy out the riparian rights of existing landowners along the lake (e.g., their right of access to the water), the legislature authorized the park districts to enter into what became known as "boundary agreements." By fixing the boundary of the retained property somewhat more to the east (into the lake), these agreements gave the riparian owners additional submerged land, typically about 100 feet wide, which they could fill and do with as they pleased. This land was no longer in the water or at its immediate edge, given the construction of the parks and drive between the new boundary and the lake (farther) to the east, but it was more land for the private party. No lawsuit was ever filed challenging this massive disposition of submerged land as a violation of the public trust.

Other public projects that entailed landfilling approved by the legislature also passed muster with little controversy. The construction of Navy Pier (begun in 1914), of a water filtration plant (approved in 1954), and of the McCormick Place convention center (1958) all fit this description. The latter two projects stimulated litigation, primarily by taxpayers objecting to the cost, but attempts to raise the public trust as grounds for objection were brushed aside by the courts with a perfunctory analysis.

The most striking illustration of the state of the public trust doctrine was the decision by Northwestern University, in the early 1960s, to double the size of its campus in Evanston by landfilling in the lake. The university's lawyers advised that the project could go forward so long as the legislature approved a grant of the submerged land for this purpose and the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers signed off that the new land would not interfere with navigation. The lawyers were familiar with the Illinois Central decision, but counseled that it was "very old" and "obsolete." They were right: with the blessing of the legislature and the Army Corps, the project elicited no recorded objection based on the public trust doctrine (or on any other basis to speak of).

In 1970, this minimalist conception of the public trust suddenly changed. Professor Sax published in that year what is undoubtedly the most consequential article ever written about the public trust doctrine. The article was motivated by Sax's fear that public authorities could be induced to convey valuable public lands to private interests with little input from the public. He recognized that change is inevitable, and he did not oppose all such transfers. But he argued that the public trust doctrine, as invoked in the Illinois Central decision and in other scattered cases outside Illinois, could be reformulated to require some kind of public approval process before such transfers take place, with courts applying a sufficiently probing review to assure that proper deliberation and consideration of the public interest had occurred.

Later that same year, the Illinois Supreme Court heard a challenge to a proposal to transfer a portion of an inland public park on the South Side for the construction of a public school (this was Washington Park). The plaintiffs in the case, Paepcke v. Public Building Commission, challenged the proposal on statutory grounds, under the public dedication doctrine, and under the public trust doctrine. The court was unanimous in rejecting the challenge on all counts. But as fate would have it, the assignment to write the opinion went to one Justice Marvin F. Burt, who had recently been appointed to fill a vacancy on the court created by the resignation of a justice embroiled in a scandal. Burt, a longtime supporter of public parks, wrote an opinion that illustrates the power of the sequencing of issues and of dicta.

Burt's opinion in Paepcke concluded several things, explicitly or implicitly: (1) that any taxpayer in Illinois has standing to bring a public trust claim; (2) that the common-law public dedication doctrine (the topic of our third post) is no longer of any force in Illinois; (3) that the public trust applies to a public park, without regard to whether it sits on land that was once under navigable waters; and (4) that the public trust doctrine is not limited to protecting the public's interest in accessing navigable waters to engage in commerce or fishing, but applies to any decision to subject public resources "to more restricted uses or to subject public uses to the self interest of private parties."

For the last proposition, including the emphasis, Justice Burt quoted with approval the law review article published earlier that year by Professor Sax. Without anything that could be described as meaningful analysis, he then proceeded to approve the use of the park for construction of a school as consistent with the public trust, generating the disposition of the case—which rejected the plaintiffs' challenge on all counts—as approved by all the other justices.

After Paepcke, the public trust doctrine in Illinois took a very different turn. It would be flattering to the law professoriate to think that Professor Sax should be credited with the change. His article unquestionably was consulted by Justice Burt, and gave the justice confidence that the public trust doctrine was the ticket to enlisting the courts in the cause of providing greater protection to public parks.

Yet the precise proposal advanced by Sax—a call for greater deliberation through public hearings before public lands are turned over to private interests—makes no appearance in Burt's opinion. Sax would have applauded universal citizen standing, the implicit extension of the public trust to resources other than those connected with navigable waters, and the caution against giving politicians free rein to transfer public resources to private interests. But he would have been perplexed by the absence of any institutional mechanism to ascertain the public will, other than the occasional lawsuit asserting a violation of a nebulous trust doctrine.

Primary credit for the transformation of the public trust doctrine must be given to the temper of the times. The year 1970 saw the first Earth Day in April, with widespread public demonstrations supporting greater environmental protection. Congress got into the act, passing the National Environmental Policy Act and the Clean Air Act. The Nixon Administration created the Environmental Protection Agency by executive order, using reorganization authority since repealed. And the D.C. Circuit was busy giving a "hard look" to governmental decisions affecting the environment.

Paepcke was yet another manifestation of this public mood. Sax's role was to legitimate what one member of the Illinois Supreme Court wanted the law to say. Paepcke put the public trust doctrine on a new path. But, as we shall see in our fifth and final post, that path was not at all clearly marked.

Show Comments (1)