The Volokh Conspiracy

Mostly law professors | Sometimes contrarian | Often libertarian | Always independent

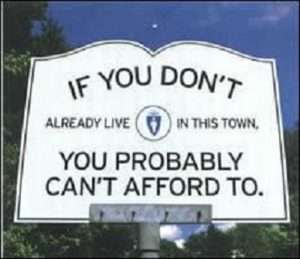

A Cross-Ideological Case for Ending Exclusionary Zoning

A recent Century Foundation report highlights reasons why breaking down barriers to building new housing should appeal to left, right, and libertarians alike.

The Century Foundation recently published "Tearing Down the Walls: How the Biden Administration and Congress Can Reduce Exclusionary Zoning." In it, Century Foundation Senior Fellow Richard Kahlenberg summarizes the harm caused by exclusionary zoning, and summarizes several proposed ways the federal government can help reduce it. The report represents Kahlenberg's views. But it is based in part on a conference on zoning held by the Century Foundation in December, which included a wide range of academics and policymakers, including myself.

I don't agree with Kahlenberg on every point. But he's absolutely right about the great extent of the problem, and the ways in which it cuts across ideological lines:

While democratic egalitarianism and the liberty to be free from government interference are values that are typically in tension with one another, in the case of exclusionary zoning, they point in the same direction. Perhaps because curtailing exclusionary zoning honors both egalitarian (anti-discriminatory) and libertarian (small government) streams in the American belief system, surveys suggest it is popular. In a 2019 Data for Progress poll, for example, voters were asked, "Would you support or oppose a policy to ensure smaller, lower-cost homes like duplexes, townhouses, and garden apartments can be built in middle- and upper-class neighborhoods?" Supporters outnumbered opponents by two to one.

Kahlenberg expands on this theme in a recent New York Times op ed:

Blue cities and states — most notably Minneapolis and Oregon — have recently led the way on eliminating single-family exclusive zoning, as a matter of racial justice, housing affordability and environmental protection. But conservatives often support this type of reform as well, because they don't want government micromanaging what people can do on their own land. At the national level, some conservatives have joined liberals in championing reforms like the Yes in My Backyard Act, which seeks to discourage exclusionary zoning.

As Kahlenberg points out in both articles, cutting back on zoning would serve progressive values by expanding housing and job opportunities for the poor, and by eliminating restrictions that, in many cases, were originally established for the purpose of keeping out African-Americans and other racial minorities. In recent years, some liberal jurisdictions have undertaken important reforms in this field, most notably Minneapolis and Oregon (as Kahlenberg notes). But there is still a tension between the growing recognition that zoning is inimical to liberal values, and the high degree of NIMBY sentiment in many liberal areas:

If race were only the driving factor behind exclusionary zoning, one would expect to see such policies most extensively promoted in communities where racial intolerance is highest, but in fact the most restrictive zoning is found in politically liberal cities, where racial views are more progressive. Indeed, some liberals even take special pride in the fact that particular neighbors of theirs are members of racial or ethnic minority groups….

[S]ome upper-middle-class liberals will strenuously argue that people should never be denied an opportunity to live in a neighborhood because of race or ethnic origin, but have no problem with government policies that effectively exclude those who are less educationally and financially successful. As Princeton political scientist Omar Wasow acerbically noted: "There are people in the town of Princeton who will have a Black Lives Matter sign on their front lawn and a sign saying 'We love our Muslim neighbors,' but oppose changing zoning policies that say you have to have an acre and a half per house." He continues: "That means, 'We love our Muslim neighbors, as long as they're millionaires.'"

There are similar tensions on the right between free market economists and property law experts who recognize that zoning reform can eliminate severe restrictions on property rights and vastly expand economic growth, and those who sympathize with Donald Trump's claims during the last election, that exclusionary zoning is needed to protect white middle-class neighborhoods against an influx of the poor and minorities.

In both of his articles, Kahlenberg correctly argues that reducing exclusionary zoning will help alleviate both racial injustice and economic inequality. As I have previously pointed out, this is an issue on which the largely Republican white working class and mostly Democratic African-American and Hispanic workers have an important common interest.

It is worth emphasizing, moreover, that the racial angle here is not simply about alleviating "structural racism" in some very broad sense of the word that would understandably raise conservative and libertarian hackles. Rather, many of today's exclusionary zoning policies were originally enacted for the specific purpose of keeping out blacks (and sometimes other minorities, as well). That's racial discrimination even under the narrowest plausible definition thereof. Anyone who advocates color-blind government policy (as many on the right - for good reason - do), cannot overlook this history.

I wish, however, that Kahlenberg had also emphasized the ways in which zoning reform not only benefits the poor and minorities, but also can greatly increase economic growth, thereby ensuring gains for society as a whole. As Matt Yglesias points out in a thoughtful analysis of Kahlenberg's articles, survey data suggests that the economic growth aspect of the issue actually has broader appeal than the racial justice frame. The latter has value in appealing to committed progressives - an important constituency in many of the liberal areas that have some of the most egregious zoning restrictions. But the former is crucial to building a broader cross-ideological coalition.

Recent evidence suggests that the zoning stifles growth to an even greater extent than previously recognized. Reform advocates should do all they can to make that fact more widely known.

I will not, in this post, offer a detailed assessment of the specific policy proposals outlined in the Kahlenberg/Century Foundation report. My general view is that there is some real merit in proposals to condition various federal grants to states and localities on zoning reform. I am more wary of more comprehensive federal efforts to override local land-use policy. However, for reasons I laid out in a 2011 article on this topic, there may be good reasons for such overriding in cases where it expands protection for property rights, and thus gives individual property owners the ultimate say in deciding how to use their land, as opposed to imposing some kind of centralized federal land-use plan. Curbing state and local restrictions on property rights can actually increase decentralization, overall. The most localist land-use policy and the one that takes greatest account of diversity and local knowledge is one under which property owners have broad autonomy in deciding how to use their land.

While the federal reforms Kahlenberg describes deserve consideration, I believe the greatest potential for reform may lie at the state level, building on recent successes in Oregon and elsewhere. If state Rep. Scott Wiener is able to push through his proposed reforms in California, it could be a game-changer for the entire nation.

Reformers should also make greater use of referendum initiatives to promote zoning reforms. I outlined some of the reasons why here. In addition, they should systematically look for ways to challenge exclusionary zoning under various property rights provisions of both state and federal constitutions - a subject I plan to write about more in the future.

There aren't many policy changes that can simultaneously strengthen protection for property rights, increase opportunity for the poor, alleviate grave historic racial injustices, and greatly expand economic growth. Abolishing exclusionary zoning can do it all! Whether you're a libertarian, a conservative property rights advocate, a racial justice crusader, a progressive concerned about economic inequality, or just someone who wants to lower housing prices because "the rent is too damn high," this is a cause you have good reason to support.

UPDATE: In the original version of this post, I accidentally called the Century Foundation the "Century Fund." I apologize for the error, which has now been corrected.

Editor's Note: We invite comments and request that they be civil and on-topic. We do not moderate or assume any responsibility for comments, which are owned by the readers who post them. Comments do not represent the views of Reason.com or Reason Foundation. We reserve the right to delete any comment for any reason at any time. Comments may only be edited within 5 minutes of posting. Report abuses.

Please to post comments

I have a lot of black people in my neighborhood. They are professional basketball players, and hit making musicians. I have no problem with that. They worked hard to live there. Some of their kids had wild parties, but they took care of the problem, themselves. Now Ilya wants to return them to the Democrat hellscapes from which they escaped.

That being said, Ilya needs to provide the home address. We are sending the illegals and the urban people to live in his upstairs bedrooms.

Keep our Jewish neighborhoods pure.

Schvartze Goyim OUT!

My black neighbors are far less annoying and supercilious than most of my other neighbors. They are also modest, and will gladly speak to ordinary people.

Move the matzah shops to the edge of your neighborhood and hide the bagel shops out of sight. I'll walk elsewhere.

Isn't Nimby-ism is the ultimate Libertarian (and democratic) ideal?

People choosing to live their lives and shaping their communities the way they want to?

Either Nimbys can have a say in how their properties and communities are organized, or they can't.

I support property rights which means I acknowledge I don't have a veto over use of the undeveloped lots in my neighborhood. Perhaps I am not a true Libertarian.

But you do, through the democratic process, have a say (i.e. veto or authorization), over your community (e.g. zoning, taxes, schools, police, golf courses, etc.).

Whether you choose to use that power is up to you.

Ugh...edit function!!!!!

The most Libertarian of all ideas, moving (zoning) laws away from the local government to the state of even federal level.

Really?

The top land use planning issue in my town is keeping the town's quota of affordable housing away from the richer residents. The town negotiated with a developer to put those people at the edge of town. The planning board is afraid that too many in-law apartment permits will be granted. Apartments count as housing units and could drop the fraction of affordable housing below the state target of 10%. Then a developer could build anywhere.

Location, location, location is always a primary issue when purchasing a home. Where the home is is often far more important than its mere physical attributes (which can be changed with renovations). People want (now more than ever) to share commonalities with their neighbors.

Me? I want to live where the police are fully funded and my neighbors feel free to (and do) call them when some guy is loitering outside my window, rummaging through my mail, or hopping over my fence; the schools don’t teach “hate America (because I AM America), realize that math really does have a one correct answer, children are taught how to think, not what to think, and, everyone is treated equally; my neighbors pick up their own trash, and carry their own weight (pay for their own stuff); and where people think MY life matters even though I’m not participating in the victimization Olympics. So yes, I don’t want to live with people who don’t share my values, and surprisingly, what you call exclusionary zoning works (albeit imperfect at times) for that.

I don’t mind people having different views, or living with different values - they can live their life as they wish. But their values and priorities should not be foisted upon me. I think the “right to not associate” is increasingly becoming more important. Much like others don’t have the right to touch non-consenting others (omg, another of my values), nor should they have the right to another’s association. Much as people choose their life partners, they should be able to choose the neighborhood (the culture) they want to live in. Bottom line - others don’t have the right to me and I don’t have the right to them.

Exclusionary zoning does not guarantee the combination in your second paragraph. I think you'd like the police in my town but you'd hate the schools.

It was fun when there were a townwide alert about a suspicious masked man going around. A resident pointed out he was black and a thousand people felt conflicted. We don't want strange people wandering around town but we don't want to overtly tell the cops "go after that black guy." He turned out to be harmless. Just another door to door salesman. I bet he would have been more fun to talk to than the salesmen who made it to my door unmolested.

Door and door locks don’t guarantee home security, but I still have a door and lock it.

And shaming people into not reported suspicious activity is exactly what lets crime thrive. Too often, the difference in crime rates among neighborhoods is the willingness of residents to become invoked and report - to look out for each other, not the criminals. So yes, importing that “let’s not snitch” value not a positive for the neighborhood and yet another reason for exclusionary zoning. I once called police on my neighbor’s new boyfriend as he was climbing through her window (he actually appreciated that his new girlfriend had nice neighbors, so it’s all in perspective). People who don’t value the community, don’t belong in that community.

But, the critical issue is that people shouldn’t have to compulsorily associate with other people. Who we marry, live with, share life with are choices for free people. You can’t force people to be friends, and forcing parasitic relationships is not sustainable.

Curious that Somin asserts that progressive policies are more likely to result in racially tolerant attitudes.

By my observation, racial tolerance is maximized in areas with low population density. Areas almost universally devoid of progressive majorities. Areas where government involvement in daily life is minimized.

}}} but in fact the most restrictive zoning is found in politically liberal cities, where racial views are more progressive.

Oh, please. Liberals are the biggest damned racist group among white people, by far. The only two college-educated people I KNOW who have used the "N word" to refer to them both self-identify as "Yellow Dog Democrats".

Ami Horowitz' Voter ID short also highlights the inherent racist "soft bigotry of low expectations" behind the "Voter ID laws are racist" claim.

White liberals TALK about hating racism, but it's all talk. They constantly assume black people NEED help because clearly black people can't manage to do what pretty much everyone referred to as "asian" has managed (esp. Indians and the Chinese) to accomplish despite experiencing little if any better treatment in the USA following the Civil War and extending to about 1960 or 1970, including lynching, segregation, and plenty of derogatory assumptions.

If they actually had to be NEAR actual black people, they'd be cringing whenever they thought they weren't being watched.