The Volokh Conspiracy

Mostly law professors | Sometimes contrarian | Often libertarian | Always independent

If Donald Trump is Convicted of Violating 18 U.S.C. § 2383, Will He Be Disqualified From Serving As President?

[This post is co-authored with Seth Barrett Tillman.]

The impeachment process has now drawn to a close. It remains to be seen whether Congress pursues any legislation concerning Section 3 of the Fourteenth Amendment. It is possible that Donald Trump may be sued civilly under a variety of causes of action. Indeed, a member of Congress has already sued Trump for violating the Ku Klux Klan Act of 1871. And, as Jonathan Adler pointed out, Trump may face a criminal prosecution. This post focuses on the consequences should Trump be convicted for violating 18 U.S.C. § 2383. (We flagged this statute in our February 3 post on incitement.) § 2383 provides:

Whoever incites, sets on foot, assists, or engages in any rebellion or insurrection against the authority of the United States or the laws thereof, or gives aid or comfort thereto, shall be fined under this title or imprisoned not more than ten years, or both; and shall be incapable of holding any office under the United States. (emphasis added)

We expect that, by now, readers of this blog are well familiar (if not exhausted) with our arguments concerning the phrase "office . . . under the United States." Prior to 2017, our position about the meaning of this phrase was not widely known, and it had few real-world implications. Yet, we continue to be amused how often Trump-related issues have implicated the phrase "office . . . under the United States." This issue has arisen in debates over the Foreign Emolument Clause, the Impeachment Disqualification Clause, Section 3 of the Fourteenth Amendment, and potentially a criminal prosecution under § 2383. Indeed, the Ku Klux Klan Act we referenced earlier also makes use of "office . . . under the United States"-language. Time and again, our position has become relevant to important contemporary legal issues.

We've written that the phrase "office . . . under the United States" refers to appointed positions in the Executive and Judicial Branches, and also includes appointed positions in the Legislative Branch. This phrase does not extend to elected federal positions, i.e., the President, Vice President, and members of Congress.

The phrase "office . . . under the United States" is used in several clauses in the Constitution. This language also appears throughout the body of federal statutes, including statutes passed by the First and other early congresses. In our experience, most people simply assume that this language extends to all positions in the federal government—appointed and elected. But that assumption is particularly problematic in the context of statutory disqualification. The Supreme Court and other federal courts have held that congressional statutes cannot add additional qualifications for elected federal positions. Of course, Congress can add statutory qualifications for appointed positions. In other words, Congress can add statutory qualifications to the positions it creates (i.e., appointed federal positions), but Congress cannot add qualifications to positions created by the Constitution (i.e., elected federal positions).

Is a person convicted under § 2383 disqualified from holding an elected federal position? Under settled modern Supreme Court and other federal court precedent, this statute should not be read in that fashion. Indeed, we also think that reading is correct as a matter of original public meaning—at least with respect to the Constitution of 1788. Later in this post, we will address the effect of Section 3 and Section 5 of the Fourteenth Amendment.

I. Under the Constitution of 1788, Congress cannot add qualifications for elected federal officials.

In Federalist No. 60, Hamilton argued that Congress lacks the power to add to the qualifications for elected federal positions. In that paper, Hamilton wrote, "[t]he qualifications of the persons who may choose or be chosen [for a seat in Congress], as has been remarked upon other occasions, are defined and fixed in the Constitution, and are unalterable by the legislature." And Powell v. McCormack (1969) concluded that James "Madison had expressed similar views in [Federalist No. 52], and his arguments at the Convention leave no doubt about his agreement with Hamilton on this issue." Ultimately, Powell largely ratified Hamilton's position.

The Supreme Court reaffirmed this historical analysis in U.S. Term Limits v. Thornton (1995). This case examined whether the states, as opposed to Congress, have the power to add to the Constitution's qualifications for elected federal positions. In Thornton, the Court explained: "the debates at the state conventions . . . 'also demonstrate the Framers' understanding that the qualifications for members of Congress had been fixed in the Constitution.'" Justice Thomas dissented in Thornton. He concluded that the Constitution did not restrict the state's power to impose qualifications on holding elected federal positions. But Justice Thomas did not express disagreement with Powell, which held that Congress lacks the power to impose qualifications on holding elected federal positions. In Thornton, Thomas wrote, "In particular, the detail with which the majority recites the historical evidence set forth in Powell v. McCormack [suggesting that Congress lacks the power to impose qualifications on elected positions], should not obscure the fact that this evidence has no bearing on the question now before the Court [concerning state-imposed qualifications]." We take no position on whether the Constitution prohibits the states, rather than the federal government, from imposing additional qualifications on members. We agree with Powell and Justice Thomas' dissent in Thornton: as a matter of original public meaning, we think that Congress cannot detract from, add to, or amend the qualifications the Constitution specifies for elected federal positions.

Moreover, the lower court courts have extended the holding of Powell to the presidency. For example, in a 2000 case, Chief Judge Posner wrote that Congress could not modify the requirement "that the President [must] be at least 35 years old." A federal statute requiring the President to reach the age of 40 would be plainly unconstitutional. Here, Posner cited Powell and Thornton. Other district courts have reached similar conclusions. Professor Derek Muller observed, "Courts have occasionally treated the holding in U.S. Term Limits, Inc. v. Thornton, which found the qualifications for members of Congress enumerated in the Constitution as exclusive, applicable to presidential elections, too."

Congress has authority under Article I to impose qualifications for the positions that it creates—that is, appointed federal positions. But Powell and Thornton, and other federal court precedents, have held that Congress does not have authority to impose qualifications for positions created by the Constitution—that is, elected federal positions. We find some support for this position in a 1790 Anti-Bribery Statute enacted by the first Congress.

II. The 1790 Anti-Bribery Statute should not be read to impose additional qualifications on elected federal positions.

In 1790, Congress enacted an anti-bribery statute: An Act for the Punishment of Certain Crimes, 1 Stat. 112, 117 (1790). The law declared that a defendant convicted of bribing a federal judge:

shall forever be disqualified to hold any office of honor, trust, or profit under the United States.

This language mirrors the text of the Disqualification Clause, which provides:

Judgment in Cases of Impeachment [by the Senate] shall not extend further than to removal from Office, and disqualification to hold and enjoy any Office of honor, Trust or Profit under the United States. (emphasis added).

If the presidency is an "Office of honor, Trust or Profit under the United States," then the 1790 statute purports to add a new qualification for the presidency. But Congress does not have the power to add, by statute, new qualifications for the presidency or for members of Congress. We agree with Chief Judge Posner: a statute that required the President to "attain[] the Age" of 40, instead of 35, would be plainly unconstitutional.

If the President and other elected federal officials hold "Office[s] . . . under the United States," then the 1790 anti-bribery statute would be unconstitutional. We raised this position in the Emoluments Clauses litigation. The Civil Division of the Department of Justice, which represented the President in his official capacity, agreed with our argument. DOJ stated:

[T]he 1790 Act enacted by the First Congress would in fact run afoul of such restrictions if applied to Members of Congress or the President, if such officials hold 'offices under the United States.' Defendant's Supplemental Brief in Support of his Motion to Dismiss and in Response to the Briefs of Amici Curiae, Blumenthal v. Trump, Dkt. No. 51 (D.D.C. April 30, 2018), https://bit.ly/2M6sBSZ.

If Congress had tried to impose new qualifications on elected federal positions in 1790, we would expect some members to have dissented. We would expect there to be some record of objections in the Executive Branch or in the press. But we have found no such debates. And after four years of litigation in the Emoluments Clauses litigation, our critics have not identified any such objections. The better view is that the First Congress used the phrase "Office . . . under the United States" to refer to appointed federal officers, and not to elected federal officials. We think this phrase was so understood in 1790. This understanding explains, and as best as we can tell, why there was no recorded debate on this issue.

During the Early Republic, Congress imposed disqualifications against federal appointed officers convicted of certain crimes. Those statutes also used the phrase "office . . . under the United States." For example, the Treasury Act from 1789 provided that a wrongdoer "shall . . . forever thereafter [be] incapable of holding any office under the United States." That statute could not bar a person from serving as President or as a member of Congress. There were more than a few such federal statutes.

We should hesitate before concluding that the First Congress, which included several Framers and ratifiers, enacted a plainly unconstitutional statute. We should hesitate before concluding that President Washington signed a plainly unconstitutional statute. And we should be especially cautious to conclude, more than two centuries later, that the First Congress and President Washington acted unconstitutionally—when there are no known reports from that time in which anyone alleged these actions were unconstitutional.

The Supreme Court has recognized that a special solicitude is afforded to the First Congress. We recognize that early Congresses took actions that the courts later disapproved of. But such disputes concerned highly controversial legislation, such as the Sedition Act, or highly complex and technical legislation, such as the Judiciary Act of 1789. Marbury v Madison, for example, considered the Judiciary Act of 1789. This landmark law implemented a new complex statutory system. There is no record indicating that the 1790 Anti-Bribery Act's "Office . . . under the United States" language, and whether that language extended to elected federal positions, were hotly debated in Congress or by the public. The Judiciary Act of 1789 built an entirely new structural "constitution" for the judiciary. In contrast, the 1790 Act used an extant, if not a long-standing, drafting convention: "Office . . . United States." Its genealogical progenitor was "office . . . under the crown."

The 1790 bribery statute and 18 U.S.C. § 2383 both disqualify a convicted person from holding an "office . . . under the United States." Under the Constitution of 1788, we do not think Congress can impose additional qualifications on elected federal positions. Therefore, the better view is that the phrase "office . . . under the United States" as used in these two statutes, and in many other disqualification statutes, does not extend to elected federal positions like the presidency and members of Congress. However, the analysis may be different in light of the Fourteenth Amendment.

III. Do Sections 3 and 5 of the Fourteenth Amendment Give Congress the Power to Impose Additional Disqualifications On Holding Office?

Under the Constitution of 1788, Congress cannot impose additional qualifications on the presidency and members of the House and Senate. But the Fourteenth Amendment gave Congress a new power. Specifically Section 3 disqualified certain people from holding certain positions in certain circumstances. It provides, in its entirety:

No person shall be a Senator or Representative in Congress, or elector of President and Vice-President, or hold any office, civil or military, under the United States, or under any State, who, having previously taken an oath, as a member of Congress, or as an officer of the United States, or as a member of any State legislature, or as an executive or judicial officer of any State, to support the Constitution of the United States, shall have engaged in insurrection or rebellion against the same, or given aid or comfort to the enemies thereof. But Congress may by a vote of two-thirds of each House, remove such disability.

And Section 5 gave Congress the power to enforce the Fourteenth Amendment, including Section 3. It provides:

The Congress shall have power to enforce, by appropriate legislation, the provisions of this article.

Section 3 of the Fourteenth Amendment has three elements that are directly relevant to our analysis.

First, the jurisdictional element specifies which positions are subject to Section 3. Section 3 extends to a:

person . . . who, having previously taken an oath, as a member of Congress, or as an officer of the United States, or as a member of any state legislature, or as an executive or judicial officer of any state, to support the Constitution of the United States.

Second, the offense element defines the conduct prohibited by Section 3. Specifically, the offense element regulates the conduct of a person satisfying the jurisdictional element who:

. . . shall have engaged in insurrection or rebellion against the same, or given aid or comfort to the enemies thereof . . .

Third, the disqualification element defines the legal consequences or punishment that Section 3 provides for. A person who satisfies the jurisdictional and offense elements of Section 3 shall not be:

. . . a Senator or Representative in Congress, or elector of President and Vice President, or hold any office, civil or military, under the United States, or under any state . . .

We think it is unsettled precisely how Section 3 was designed to be enforced and implemented. Our analysis, however, focuses on a different question: what are the legal consequences that apply to a person affected by the operation of Section 3? Under the original understanding of the Constitution of 1788, Congress lacks the power to impose additional qualifications for elected positions, including Senators and Representatives. But Section 3 expressly disqualifies some people from holding the position of Senator and Representative. And we have no reason to doubt that Congress could rely on its Section 5 powers to enforce this type of disqualification pursuant to Section 3.

Section 5 gives Congress the power to enforce Section 3 of the Fourteenth Amendment (that is, "the provisions of this article"). Chief Justice Chase did address Section 5 briefly in a circuit court decision, In re Griffin. But, as far as we are aware, the Supreme Court has not specifically addressed the scope of Congress' Section 5 powers with respect to Section 3. The Supreme Court has interpreted Congress' Section 5 powers with respect to Section 1 of the Fourteenth Amendment. In Boerne v. City of Flores, the Court explained that "[t]here must be a congruence and proportionality between the injury to be prevented or remedied and the means adopted to that end." Section 5 powers are not plenary. We will presume that the "congruence and proportionality" test applies to Section 5 legislation that enforces Section 3.

We think it is at least arguable that Congress could enact a criminal statute, pursuant to the Fourteenth Amendment, that would disqualify a defendant from serving in Congress if that person falls within the jurisdictional element and committed the conduct described in the offense element. Why? Because the disqualification element of Section 3 includes an express bar against holding a congressional position. Could Congress also enact a criminal statute, pursuant to the Fourteenth Amendment, that would disqualify a defendant from serving as President? The answer to this question is more complex. The disqualification element of Section 3 expressly lists a bar against holding a congressional post, but there is no such express bar against serving as President. The only way for the presidency to be covered by the disqualification element of Section 3, is if the presidency is an "office . . . under the United States." We think this issue is difficult with respect to Section 3. We have avoided reaching any firm conclusion on this aspect of Section 3 in our prior publications. And for the reasons that we will explain below, this question can be avoided with respect to the scope of statutory disqualification under § 2383.

Could Congress enact a criminal statute, pursuant to the Fourteenth Amendment, that would disqualify a defendant from holding elected federal positions, including the presidency? Perhaps. But in light of the history of § 2383, we do not think this statute could disqualify a defendant from serving as president. And we think § 2383 cannot impose such a disqualification, even if you might have views which diverge from our own about the meaning of the phrase "office . . . under the United States" as used in the Constitution of 1788, or as used in the Fourteenth Amendment, or both.

IV. The History of 18 U.S.C. § 2383.

18 U.S.C. § 2383, in its present form, provides:

Whoever incites, sets on foot, assists, or engages in any rebellion or insurrection against the authority of the United States or the laws thereof, or gives aid or comfort thereto, shall be fined under this title or imprisoned not more than ten years, or both; and shall be incapable of holding any office under the United States. (emphasis added).

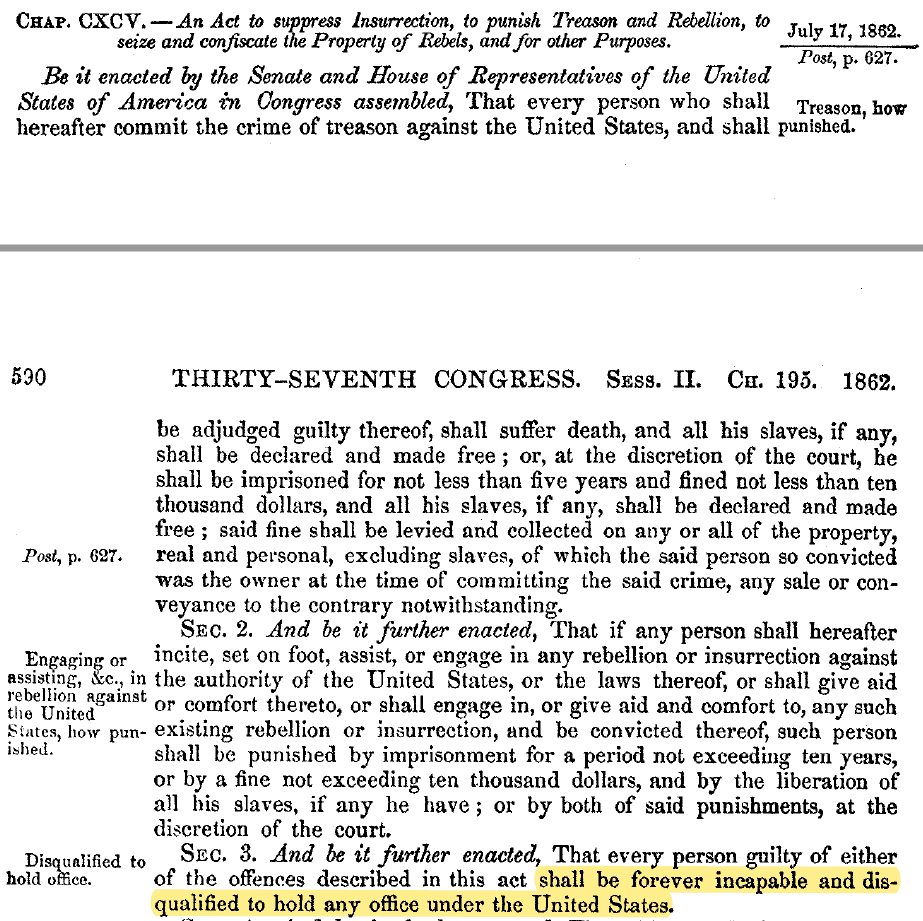

This modern statute, now reported at 18 U.S.C. § 2383, was enacted by the 37th Congress, as the Act of July 17, 1862.

First, the Act of July 17, 1862 law can be found at 37 Stat. 590, ch. 195, § 2. It includes the same two core elements of 18 U.S.C. § 2383.

The predicate offense is defined as "incite, set on foot, assist, or engage in any rebellion or insurrection." And the disqualification element states that a convicted person "shall forever be capable and disqualified to hold any office under the United States."

Statutes at Large reports that the bill was "Approved, July 17, 1862." 37 Stat. 592. President Lincoln signed this bill into law, along with an explanatory act. 37 Stat. 627, also dated July 17, 1862.

If the members of the 37th Congress and Lincoln understood the phrase "office . . . under the United States" to include elected federal positions, then the statute would impose additional qualifications on elected federal positions. And, according to Hamilton in Federalist No. 60—and the Supreme Court's not-yet-issued decision in Powell—such a statute would be unconstitutional.

What about the Fourteenth Amendment? Doesn't this 1862 statute's predicate offense track Section 3? Yes, there are similarities between the language of the statute and Section 3. And we address those similarities later in this post. But this 1862 bill was enacted before the 1868 ratification of the Fourteenth Amendment. Therefore, Congress could not have enacted this law based on its authority under Section 5 of the Fourteenth Amendment. Congress would have to rely on the Constitution of 1788. And, as explained, the original Constitution did not permit Congress to add additional qualifications for elected positions.

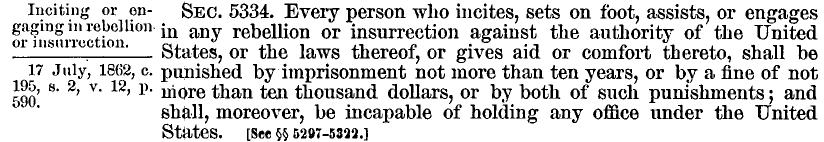

Second, a version of this 1862 statute appears in the Revised Statutes, Second Edition (1878), Section 5334, Page 1036:

Every person who incites, sets on foot, assists, or engages in any rebellion or insurrection against the authority of the United States, or the laws thereof, or gives aid or comfort thereto, shall be punished by imprisonment not more than ten years, or by a fine of not more than ten thousand dollars, or by both such punishments; and shall, moreover, be incapable of holding any office under the United States. (emphasis added)

A reproduction of the statute can be found on Hathi Trust.

The first edition of the Revised States were published in 1875, and the second edition was published in 1878. In U.S. v. Bowen (1879), Justice Miller observed that Revised Statutes "must be treated as the legislative declaration of the statute law on the subjects which they embrace on the first day of December, 1873." An 1879 decision from the Court of Claims observed, "It was no doubt the desire and understanding of Congress that the revision should generally reproduce and express the pre-existing laws so far as it was practicable to do so." Wright v U.S. (1879) (Richardson, J.).

The second edition of Revised Statutes was published in 1878, a decade after the ratification of the Fourteenth Amendment. Yet, there is no evidence that Congress sought to invoke Sections 3 and 5 of the Fourteenth Amendment. And even if Congress had tacitly invoked Sections 3 and 5 of the Fourteenth Amendment as an additional enumerated power to authorize the statute, there is no evidence Congress sought to change the meaning of the statute's "office under the United States"-language. To the contrary, the history of this statute suggests the meaning of "office under the States" was unchanged from 1862 to 1878.

Other laws passed in that era did expressly rely on Section 3's references to specific positions or classes of positions. For example, in 1870, Congress enacted an Act to Enforce the Right of Citizens of the United States to Vote in the Several States of this Union, ch. 114, § 15, 16 Stat. 140, 143–44 (1870). Section 15 of the statute specifically invoked Section 3 of the Fourteenth Amendment. It provides:

That any person who shall hereafter knowingly accept or hold any office under the United States, or any state, to which he is ineligible under the third section of the fourteenth article of amendment of the Constitution . . . shall be deemed guilty of a misdemeanor against the United States . . . (emphasis added).

Congress knew how to invoke Section 3. And Congress knew how to refer to the specific positions or classes of positions referenced in Section 3. We think the meaning of the insurrection statute was unchanged between 1862, when President Lincoln signed it, and the publication of the Revised Statutes a decade later.

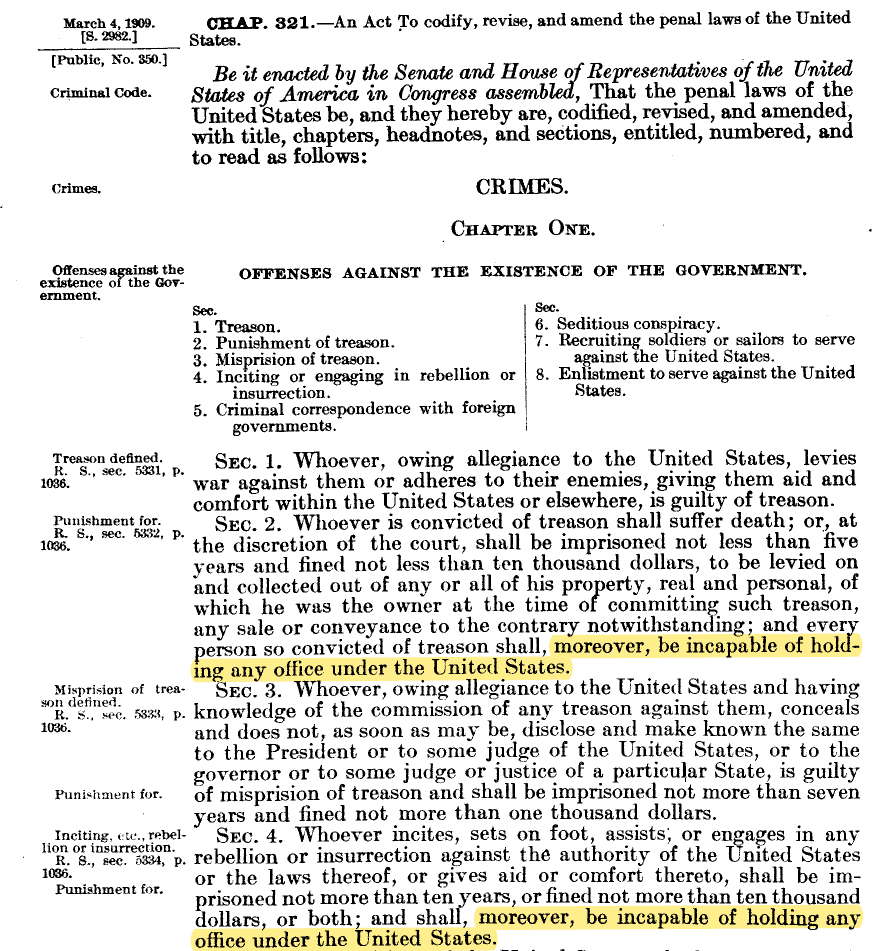

Third, in 1909, a revised version of the insurrection statute appeared in 35 Stat. 1088. This Act of Congress codified, revised, and amended the penal laws of the United States. Section 4 provides:

Whoever incites, sets on foot, assists, or engages in any rebellion or insurrection against the authority of the United States or the laws thereof, or gives aid or comfort therefore, shall be imprisoned not more than ten years, or fined not more than ten thousand dollars, or both; and shall, moreover, be incapable of holding any office under the United States. (emphasis added)

Section 4 from 1909 is very similar to the version that appeared in Revised Statutes (Second Edition). But there are slight revisions. "[E]very person" was changed to "Whoever." "[S]hall be punished by imprisonment" was changed to " shall be imprisoned." "[O]r by a fine of not more than" was changed to "or fined not more." For our analysis, the most important element—"shall, moreover, be incapable of holding any office under the United States"—was unchanged.

If Congress understood the phrase "office under the United States" to include elected positions, then the statute would run afoul of Hamilton's reading of the 1788 Constitution. Perhaps, with this amendment. Congress sought to rely on its Section 5 powers to enforce Section 3. By 1909, the Fourteenth Amendment was well established. And Congress had already enacted legislation regarding Section 3, including the 1870 statute discussed above. But there is no evidence Congress sought to invoke Sections 3 and 5 of the Fourteenth Amendment through the 1909 amendments. And even if Congress had tacitly invoked Sections 3 and 5 of the Fourteenth Amendment as an additional enumerated power to authorize the statute, there is no evidence Congress sought to change the meaning of the statute's "office under the United States"-language. The changes made in 1909 were purely technical. There is no indication that Congress intended to deviate from the meaning of the statute enacted in 1862.

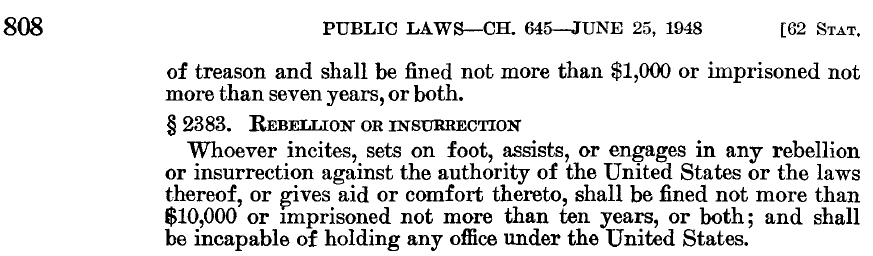

Fourth, in 1948, the 80th Congress made a minor technical change to the language of the statute. It can be found at 62 Stat. 808:

Whoever incites, sets on foot, assists, or engage in any rebellion or insurrection against the authority of the United States or the laws thereof, or gives aid or comfort thereto, shall be find not more than $10,000 or imprisonment not more than ten years, or both; and shall be incapable of holding any office under the United States. (emphasis added)

The only change was the deletion of the word "moreover" after "shall." Westlaw includes a notation from the House Report:

Word "moreover" was deleted as surplusage and minor changes were made in phraseology. 80th Congress House Report No. 304.

The operative provision—"incapable of holding any office under the United States"—remained unchanged. Again, we do not have any good reason to believe this minor technical change invoked a new source of authority. There is no evidence Congress sought to invoke Sections 3 and 5 of the Fourteenth Amendment. And even if Congress had tacitly invoked Sections 3 and 5 of the Fourteenth Amendment as an additional enumerated power to authorize the statute, there is no evidence Congress sought to change the meaning of the statute's "office under the United States"-language. Had Congress enacted an altogether new statute in 1948 that used the phrase "office under the United States," we would try to determine how that phrase was understood in 1948. But in this context, the statute was re-enacted with no substantive changes. In our view, Congress has taken no action to alter the meaning of the phrase "office under the United States" since 1862.

Fifth, Congress amended the 1948 insurrection statute as part of the omnibus Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act of 1994.

Section 330016 of that bill, titled, "CORRECTION OF MISLEADING AND OUTMODED FINE AMOUNTS IN OFFENSES UNDER TITLE 18," revised the fine amount in many statutes, including 18 U.S.C. § 2382. There was only one change: "not more than $10,000" was changed to "under this title."

Westlaw included a notation with Section 330016:

1994 Amendments. Pub. L. 103-322, § 330016(1)(L), substituted "under this title" for "not more than $10,000".

Today, 18 U.S.C. 2382 provides:

Whoever incites, sets on foot, assists, or engages in any rebellion or insurrection against the authority of the United States or the laws thereof, or gives aid or comfort thereto, shall be fined under this title or imprisoned not more than ten years, or both; and shall be incapable of holding any office under the United States. (emphasis added)

Again, the operative provision remains the same: "incapable of holding any office under the United States." Indeed, this language has remained virtually unchanged since 1862. Once again, there is no evidence Congress sought to invoke Sections 3 and 5 of the Fourteenth Amendment. And even if Congress had tacitly invoked Sections 3 and 5 of the Fourteenth Amendment as an additional enumerated power to authorize the statute, there is no evidence Congress sought to change the meaning of the statute's "office under the United States"-language. This omnibus bill made technical changes to many statutes. Congress did not alter the meaning of the phrase "office . . . under the United States." There is a direct, unbroken chain between the 1994 statute and Abraham Lincoln's signature on the 1862 statute.

We do not think this statute, 18 U.S.C. § 2383, which traces in almost unchanged form to its enactment in 1862, is premised on Congress' Section 5 powers. In short, under the Constitution of 1788, and the Constitution, as it stood in 1868, 18 U.S.C. § 2383 should not be read to impose qualifications on elected federal positions.

We think this conclusion answers the question posed by the title of this post: if Donald Trump is convicted of violating 18 U.S.C. § 2383, he would not be disqualified from serving as president. Next, we will consider this analysis under a hypothetical version of 18 U.S.C. § 2383 that did invoke Congress' powers under Section 5 to enforce Section 3.

V. What if A Future Congress re-enacts 18 U.S.C. § 2383 pursuant to its powers under Sections 3 and 5 of the Fourteenth Amendment?

What if a future Congress re-enacts 18 U.S.C. § 2383 pursuant to its powers under Sections 3 and 5 the Fourteenth Amendment? That is, Congress enacted a new statute that expressly found that the phrase "office . . . under the United States" in the statute had the same meaning as the phrase "office . . . under the United States" in Section 3 of the Fourteenth Amendment. And, in this hypothetical statute, Congress expressly invoked its power under Section 5 of the Fourteenth Amendment. We think this hypothetical provides a useful exercise to illustrate the interplay between the three elements of Section 3. We also recognize that some critics may not be persuaded by our discussion of the history of § 2383. The foregoing analysis will address the Fourteenth Amendment analysis for these critics.

Our hypothetical § 2383 begins with the same text as the actual § 2383. We have added two additional sections concerning the Fourteenth Amendment. It provides:

Section 1: Whoever incites, sets on foot, assists, or engages in any rebellion or insurrection against the authority of the United States or the laws thereof, or gives aid or comfort thereto, shall be fined under this title or imprisoned not more than ten years, or both; and shall be incapable of holding any office under the United States.

Section 2: For purposes of this statute, the phrase "office under the United States" shall have the same meaning as the phrase "office, civil or military, under the United States" in Section 3 of the Fourteenth Amendment.

Section 3: Pursuant to its authority under Section 5 of the Fourteenth Amendment, Congress finds that this statute is an "appropriate" and "congruent and proportional" means to enforce Section 3 of the Fourteenth Amendment.

Once again, Section 3 of the Fourteenth Amendment provides, in its entirety:

No person shall be a Senator or Representative in Congress, or elector of President and Vice-President, or hold any office, civil or military, under the United States, or under any State, who, having previously taken an oath, as a member of Congress, or as an officer of the United States, or as a member of any State legislature, or as an executive or judicial officer of any State, to support the Constitution of the United States, shall have engaged in insurrection or rebellion against the same, or given aid or comfort to the enemies thereof.

The hypothetical statute and Section 3 differ in three important regards.

First, the hypothetical statute applies to "whoever." That is, any person who engages in the proscribed conduct can be subject to disqualification. But the jurisdictional element of Section 3 does not apply to "whoever"—that is, any person. Rather, the jurisdictional element refers to four specific categories of people, including any:

person . . . who, having previously taken an oath, as a [1] member of Congress, or as an [2] officer of the United States, or as a [3] member of any state legislature, or as an [4] executive or judicial officer of any state, to support the Constitution of the United States.

Let's start with a very simple example. A defendant who never swore any oath to the Constitution cannot fall within the scope of Section 3's jurisdictional element. The prosecution of this defendant under this statute would be constitutional on its face, and as applied. The federal government is authorized to prosecute defendants for the crime of insurrection based on Congress' enumerated powers under Article I. That crime could have been prosecuted before the enactment of the Fourteenth Amendment. Moreover, Congress can prosecute a defendant for this crime even though the defendant never swore an oath to the Constitution. The authority to prosecute a defendant for this crime would derive from the Constitution of 1788, without regard to Section 5 of the Fourteenth Amendment. But, if that defendant is convicted, the statute could not disqualify him from serving in Congress. Section 3 did not authorize Congress to impose disqualifications on a person who never swore an oath to the Constitution.

What about a civil servant of the federal government who swore an oath to the Constitution, but who does not squarely fit in category #2? For example, consider a federal civil servant who is not a principal or inferior "officer of the United States." He may be what Buckley v. Valeo referred to as an "employee of the United States."If the federal civil servant were convicted of violating our hypothetical § 2383, he would not fall within the ambit of the jurisdictional element of Section 3. Therefore, that convicted civil servant could not be disqualified from serving in Congress.

What about a former President who during his entire career in public service only swore a single oath to uphold the Constitution: the presidential oath of office? Would a former President fit in category #2 as an "officer of the United States"? In a criminal prosecution under our hypothetical § 2383, the judge and jury would have no occasion to decide whether the defendant fits within any of the four categories from Section 3. The hypothetical statute does not include the defendant's having been an "officer of the United States" as an element of the offense. Thus, any determination that a former President should be disqualified based on a jury conviction where the indictment did not allege, and the jury did not find, that the President was an "officer of the United States" would offend the principles established by the Supreme Court in Blakely v. Washington (2004): the jury must determine beyond a reasonable doubt all the facts legally necessary to a sentence. A prosecution under our hypothetical § 2383 would not require the jury's finding that the defendant is an "officer of the United States." Of course we recognize that Blakely does not squarely control on the hypothetical facts.

Again, our hypothetical statute applies to "whoever." We do not think the enumeration of these four categories in Section 3 can be reduced to the phrase "whoever." Professor Gerard Magliocca has considered some evidence to the contrary. He quoted two speeches that Representative John Bingham made about Section 3. In one speech, Bingham stated:

[N]o man who broke his official oath with the nation or State, and rendered service in this rebellion shall, except by the grace of the American people, be again permitted to hold a position, either in the National or State Government. (emphasis added)

In another speech, Bingham said:

No person who took an oath of office, either Federal or State, to support the Constitution of the United States, and in violation of his oath, voluntarily engaged in the late atrocious rebellion against the Republic, shall ever hereafter, except by the special grace of the American people, for good cause shown to them, and by special enactment, be permitted to hold any office of honor, trust, or profit, either under the Government of the United States or under the government of any State of the Union. (emphasis added).

If we take Bingham at his word, a federal civil servant who does not fall within the four enumerated categories, would still be covered by Section 3's jurisdictional analysis. We would be hesitant to take Bingham so literally here. Bingham, who did not draft Section 3, was perhaps summarizing an intricate list of provisions. Or perhaps Bingham was trying to save time in his speech by using a shorthand. Or perhaps Bingham was mistaken. But the text of the jurisdictional element of Section 3 of the Fourteenth Amendment is not as broad as Bingham and others have suggested.

Indeed, the Framers could have used different language to accomplish that goal. For example, the Joint Committee of Reconstruction approved a very different version of Section 3. It focused on voter disenfranchisement, rather than disqualification. But that version of Section 3 used the phrase "all persons." It provided:

Until the 4th day of July, in the year 1870, all persons who voluntarily adhered to the late insurrection, giving it aid and comfort, shall be excluded from the right to vote for Representatives in Congress and for electors for President and Vice-President of the United States. (emphasis added).

However, the Senate did not approve the House's version of Section 3, and instead adopted the version of Section 3 that was ratified—with its intricate "office"-language. Likewise, the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment uses the language "any person." It provides that no state shall "deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws." That provision has broad scope, and it applies to "whoever" falls within a state's jurisdiction.

Instead of using "all persons"-language, the Framers of Section 3 of the Fourteenth Amendment could have simply removed the four enumerated categories from Section 3. Consider this red-lined version of Section 3:

No person shall be a Senator or Representative in Congress, or elector of President and Vice-President, or hold any office, civil or military, under the United States, or under any State, who, having previously taken an oath

, as a member of Congress, or as an officer of the United States, or as a member of any State legislature, or as an executive or judicial officer of any State,to support the Constitution of the United States, shall have engaged in insurrection or rebellion against the same, or given aid or comfort to the enemies thereof. But Congress may by a vote of two-thirds of each House, remove such disability.

That provision would have been much simpler, and that language would have cohered with Bingham's comments. But the Framers of Section 3 of the Fourteenth Amendment did not adopt such language. In short, to be covered by Section 3's jurisdictional element, one must fit within its four enumerated categories

Second, the offense element in the hypothetical statute differs from the offense element in Section 3.

The hypothetical statute applies to one who:

incites, sets on foot, assists, or engages in any rebellion or insurrection against the authority of the United States or the laws thereof, or gives aid or comfort thereto. (emphasis added).

And Section 3 applies to one who:

engaged in insurrection or rebellion against the [United States], or given aid or comfort to the enemies thereof.

There is an important word that appears in the hypothetical § 2383, but does not appear in Section 3: "incites." Under Section 3, one must "engage[] in insurrection." But the statute permits disqualification for inciting an insurrection. We think this disparity may be significant.

Let's assume a defendant is in fact covered by the jurisdictional element. That is, he fits within one of the four enumerated categories of positions. If the prosecutor secures a conviction, based upon proof beyond a reasonable doubt, that the defendant incited an insurrection, then the defendant can be punished under the statute with a fine and imprisonment. But what about disqualification? We think it likely that the defendant could be disqualified from holding an appointed position that Congress created. Congress could impose that sort of disqualification based entirely on the Constitution of 1788. We think it is unsettled whether Congress could impose a disqualification for an elected position based on incitement to an insurrection. There is a gap between engaging in insurrection, and inciting an insurrection.

Under Boerne v. City of Flores, it is not clear if this statute would "expand" the meaning of Section 3. In other words, under our hypothetical § 2383, would Congress have improperly expanded the meaning of Section 3's "engage[] in the insurrection" language by using "incites . . . insurrection" language in its hypothetical statute? We are uncertain whether this hypothetical statute is "congruent and proportional" to Section 3. We are also uncertain that Section 3 could authorize disqualification for an insurrection-related lesser-included offense, or for an inchoate crime, such as attempted insurrection, conspiracy to commit insurrection, etc. These questions are difficult. Fortunately, the judge and jury adjudicating the criminal trial under our hypothetical statute would not need to settle these questions with finality. Unfortunately, should the defendant seek to run for or hold elected federal positions after being convicted, other actors—including county and state election commissions, courts hearing appeals from such commissions, and perhaps even Congress—would need to settle these questions.

Third, the disqualification element in the statute is narrower than the disqualification element of Section 3.

The hypothetical statute extends disqualification to one category of positions: those "holding any office under the United States." And the hypothetical statute provided that:

For purposes of this statute, the phrase "office under the United States" shall have the same meaning as the phrase "office, civil or military, under the United States" in Section 3 of the Fourteenth Amendment.

The disqualification element of Section 3 is broader than the statute. It applies to 4 categories of positions:

[1] Senator or Representative in Congress, or [2] elector of President and Vice-President, or hold any office, civil or military, [3] under the United States, or [4] under any State

Both the statute and Section 3 extend to Category #3: "any office . . . under the United States." But the statute does not reference the first, second, or fourth category.

Would a conviction under this hypothetical § 2383 of engaging in insurrection disqualify a person from serving in Congress? In other words, does a member of Congress hold an "office . . . under the United States" for purposes of Section 3? The text of the disqualification element suggests the answer is "no." Section 3 lists "Senator or Representative in Congress" separately from "any office . . . under the United States." This drafting decision suggests the Framers of the Fourteenth Amendment thought that members of Congress did not hold an "office . . . under the United States." We acknowledge an alternate reading of Section 3 is possible in which a "Senator or Representative" could be a type of an "office . . . under the United States." But we think this latter reading is atextual, and is less likely. Had the Framers thought the phrase "office . . . under the United States" was a catchall that included all federal positions—appointed and elected—they would not have needed to enumerate specific elected federal positions, such as Senators and Representatives. Indeed, if Senators and Representatives were "office[s] . . . under the United States," then enumerating them separately would be redundant. The better reading is that members of Congress do not hold an "office . . . under the United States." Therefore, a conviction under the hypothetical § 2383 for engaging in insurrection would not disqualify a person from serving in Congress.

Consider this red-lined version of Section 3 that strips all specific office-language.

No person shall

be a Senator or Representative in Congress, or elector of President and Vice-President, orhold any office,civil or military, under the United States, or under any State, who, having previously taken an oath,as a member of Congress, or as an officer of the United States, or as a member of any State legislature, or as an executive or judicial officer of any State,to support the Constitution of the United States, shall have engaged in insurrection or rebellion against the same, or given aid or comfort to the enemies thereof.

Stated more simply:

No person shall hold any office, who, having previously taken an oath to support the Constitution of the United States, shall have engaged in insurrection or rebellion against the same, or given aid or comfort to the enemies thereof.

Many commentators read Section 3 as if this red-lined version was the actual text of the Constitution. It is not. In this red-lined version, the disqualification element extends to all offices, and the jurisdictional element applies to all people who swore an oath to the Constitution. But the Framers of the Fourteenth Amendment did not adopt such a simple, streamlined version of Section 3.

Would a conviction under our hypothetical § 2383 of engaging in insurrection disqualify a person from serving as President? The analysis here differs from our analysis for disqualifying a person from serving in Congress. Section 3's disqualification element expressly lists Senators and Representatives, but it does not specifically list the President. Whether the President holds an "office . . . under the United States" for purposes of Section 3 is unsettled—at least based on our survey of the extant literature. If the President does hold an "office . . . under the United States" for purposes of Section 3, then a conviction under our hypothetical § 2383 of engaging in insurrection would disqualify the defendant from serving as President. (Here, we assume that the jury would have to make all the requisite findings to satisfy Blakely v. Washington principles). But if the President does not hold an "office . . . under the United States" for purposes of Section 3, then a conviction under the hypothetical § 2383 of engaging in insurrection could not disqualify the defendant from serving as President.

Under our hypothetical § 2383, what would it take to disqualify a former President, who only swore one constitutional oath, from serving a second term? The presidency would have to fit within both the jurisdictional element of Section 3 of the Fourteenth Amendment, as well as the disqualification element of Section 3 of the Fourteenth Amendment. In other words, the President would have to be both an "officer of the United States" for purposes of the jurisdictional element and hold an "office . . . under the United States" for purposes of the disqualification element.

Conclusion

We think a criminal prosecution of Trump is unlikely; we also think a conviction unlikely should he be prosecuted. But even if Trump is convicted of violating 18 U.S.C. § 2383, we do not think he would be disqualified from running for and serving a second term as President, should he win re-election.

In order to disqualify Trump, from running for and serving a second term as President should he win re-election, on the basis of a conviction under § 2383, many legal hurdles must be overcome. Some of these hurdles would have to be overcome at the criminal trial. Other hurdles would have to be overcome in other downstream legal proceedings, for example, before county and state electoral commissions, courts hearing appeals from those commissions, and possibly Congress. Leaving aside Blakely v. Washington principles, which may apply, here we list four of those hurdles.

- The President would have to be an "officer of the United States" as that phrase is used in the jurisdictional element of Section 3 of the Fourteenth Amendment. Unlike virtually all other politicians, Trump only took one oath to support the Constitution: the presidential oath of office. He could only fit within Section 3's jurisdictional element if the President is an "officer of the United States."

- The President would also have to hold an "office . . . under the United States" as used in the disqualification element of Section 3 of the Fourteenth Amendment.

- Prosecutors would have to secure a conviction, based upon proof beyond a reasonable doubt, that Trump engaged in "insurrection." We do not think it clear that a conviction for "incitement" to commit "insurrection" is legally sufficient to disqualify Trump from running for and serving a second term as President should he win re-election.

- 18 U.S.C. § 2383 is a "congruent and proportional" means to enforce Section 3 of the Fourteenth Amendment.

If any of these hurdles are not overcome, a conviction under 18 U.S.C. § 2383 would not be sufficient to disqualify Trump from running for and serving a second term as President should he win re-election.

Our position here was not created in the wake of January 6, 2021. In 2016, Tillman publicized a similar analysis in regard to a hypothetical conviction of Secretary Clinton under 18 U.S.C. § 2071, the Federal Records Act. That statute provides:

Whoever, having the custody of any such record, proceeding, map, book, document, paper, or other thing, willfully and unlawfully conceals, removes, mutilates, obliterates, falsifies, or destroys the same, shall be fined under this title or imprisoned not more than three years, or both; and shall forfeit his office and be disqualified from holding any office under the United States. (emphasis added).

In our January 20 post, we said there is some good evidence to suggest that the President does not fit within the jurisdictional element of Section 3—that is, he is not an "officer of the United States."

If the presidency is not an "office . . . under the United States" for purposes of Section 3, then § 2383 could not be used to disqualify Trump from running for and serving as President should he win re-election. We reaffirm our position that under the Constitution of 1788, the President does not hold an "office . . . under the United States." But at this juncture, we take no position whether the President holds an "office . . . under the United States" for purposes of Section 3 of the Fourteenth Amendment. Based on our most recent survey of the extant literature, including much only published in the wake of January 6, 2021, we think this issue remains unsettled.

Going forward, the Department of Justice faces a difficult choice. There are legal and political upsides and downsides to prosecuting Trump under § 2383. If Trump were convicted, it may lead some people to conclude that he is disqualified from running for and serving a second term as President should he win re-election. We think this issue is far from clear, but recognize that election boards, courts, and even Congress could reach that conclusion. We discussed those actors in our January 20 post on Section 3. But what if Trump were acquitted of a § 2383 charge? Trump could credibly argue that he did not engage in insurrection, and thus did not run afoul of Section 3. (In much the same way, Trump could cite his two acquittals from impeachment trials as proof of his exoneration.) Therefore, the argument goes, Trump would not be disqualified from running for and serving a second term as President should he win re-election. The decision to bring this prosecution will be made at the highest levels of the Department of Justice, likely by President Biden's future Attorney General. And we suspect these legal and political risks would factor into the future Attorney General's decision. Yet, even if Trump is prosecuted and convicted, the scope of disqualification would remain for another day.

[Seth Barrett Tillman is a Lecturer at Maynooth University Department of Law, Ireland (Roinn Dlí Ollscoil Mhá Nuad).]

Show Comments (97)