The Volokh Conspiracy

Mostly law professors | Sometimes contrarian | Often libertarian | Always independent

Is there a Moral Duty to Vote in an Election Where the Stakes are Unusually High?

There could be in some situations. But less often than many assume. And, ironically, the same reasoning suggests many people would have a duty NOT to vote in such cases.

Most arguments for a moral duty to vote cast it as a general obligation of citizenship. At least as a general rule, they hold that citizens are morally required to vote in elections - regardless of how big the difference between the opposing candidates is, and regardless of which candidate the voter in question prefers. I have criticized such claims in previous writings, most recently here.

But there is another, more limited justification for a duty to vote in at least some elections. It's the idea that we have an obligation to vote in cases where the stakes are especially high. Maybe there's no duty to cast a ballot when there is little difference between the opposing candidates, or when the differences between them won't have much effect. But things are different if one side is vastly better than the other. That intuition underlies the oft-heard sentiment that you must vote because "this is the most important election of our lifetime" and other similar claims. And, as polarization has grown, we hear such claims more often.

There is a kernel of truth to the claim that you have a duty to vote if the stakes are high enough. But the resulting moral duty applies far less often than advocates of the argument tend to assume. And the same reasoning actually implies many people have a moral duty not to vote.

Let's start with the kernel of truth. Imagine there's an election for a powerful political office that pits Gandalf (the benevolent wizard in J.R.R. Tolkien's Lord of the Rings) against Sauron, the despotic dark lord from the same story. If Sauron prevails, millions of people will die or be enslaved, while Gandalf would rule justly if he manages to win. And all you have to do to ensure Gandalf's victory is check his name on a ballot. If you do so, Gandalf wins; if not, Sauron does.

In this scenario, it seems like you have a moral duty to vote for Gandalf, at least barring some kind of extraordinary exigent circumstance. In a real election, of course, the odds that your vote will make a difference are far smaller than in this stylized example. In an American presidential election, they are, on average, about 1 in 60 million, though higher in swing states.

However, a large enough difference between the two candidates could potentially justify a duty to vote for the "right" candidate, even if the odds of casting a decisive ballot are very low. For example, let's say you live in a swing state, and you have a 1 in 1 million chance of casting a decisive vote for Gandalf over Sauron. But if your vote does turn out to be decisive, you will save 1 million people from death, and 10 million from being enslaved. Some simple math leads to the conclusion that the expected value of your vote (the benefit of Gandalf's victory divided by the likelihood of having an impact) is one life saved, and ten people saved from slavery.

Here too, it may be you have a duty to vote. At the very least, there can be at least some scenarios where you have a duty to vote even if the likelihood of having a decisive impact is fairly low.

But notice that the duty in question is not an obligation to participate in the process for its own sake. It's a duty to help good triumph over evil in a situation where you can do so at little or no cost. If you have a moral duty to vote for Gandalf in these types of scenarios, it follows that you also have a moral duty not to vote for Sauron. Indeed, the person who votes for Sauron is more worthy of condemnation than the one who merely abstains. The former is actively helping evil win, while the latter "merely" chooses not to help stop it.

While Gandalf supporters may have a duty to vote, Sauron supporters actually have a duty to abstain from doing so. Ideally, they should stop supporting Sauron entirely. But they at least should not take any actions that increase the likelihood of his victory.

All of the above analysis assumes that the voter knows which candidate is superior and to what degree. But, in reality, we have widespread political ignorance, and most voters often don't even know very basic facts about how government and politics work. Most are also highly biased in their evaluation of the information they do know, functioning more as "political fans" cheering on Team Red or Team Blue, than as truth-seekers.

There is much that people can do to become better voters. But most will not actually do so, because such action requires a lot of time and energy, and may be psychologically painful. Unless and until a voter becomes well-informed about the issues and at least reasonably objective in his or her evaluation of political information, she has good reason to question her judgment about which candidate is superior, much less by how much. Thus, she cannot conclude she has a duty to vote to help the "right" side win. She may instead have a presumptive duty to abstain from voting until she meets at least some minimal threshold of political knowledge.

Perhaps the relatively ignorant and biased voter might conclude he still should vote, because he is at least less ignorant and biased than average. Thus, casting a vote would slightly improve the average quality of the electorate and perhaps slightly increase the odds of the right candidate winning. That could be true. But notice that figuring out whether you are better informed than the average voter itself requires time and effort and a certain level of preexisting knowledge. It also requires resisting the psychological temptation to think you must be better than average. Any duty to vote in such circumstances is likely to be greatly attenuated, at best.

Many people will resist this conclusion on the grounds that figuring out which side is the "right" one is actually easy, because the gap between the opposing sides is so great. All you have to do is open your eyes!

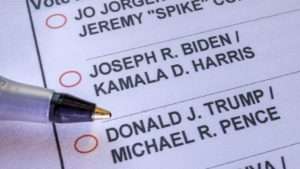

I myself think that there is a substantial gap between Biden and Trump, and that the former is the lesser evil here. It may not be quite as clearcut as Gandalf vs. Sauron; but it is perhaps roughly analogous to Sauron vs. Cersei Lannister - not good vs. evil, but a great evil vs. a much smaller one.

But if the difference between the two sides were really so obvious that almost anyone can easily figure it out, then there would be no need to worry about the election outcome! Those not otherwise inclined to vote can simply leave the decision to that portion of the population that actually enjoys voting, secure in the knowledge that the latter will easily figure out that Gandalf (or even Cersei) is preferable to Sauron.

If, on the other hand, it looks like Sauron has the support of 40% or more of the population, and therefore has something like a 10% chance of winning, that suggests discerning his relative evil is a tougher task than you might at first assume. And if the task is that difficult, your own judgment about Sauron could also be defective, unless you are relatively well-informed and unbiased.

Even if you do have good reason to be confident about your judgment about the candidates, and you justifiably believe that one is vastly superior to the other, you still might not have a duty to vote if doing so is unusually costly (for example, casting a ballot would divert you from some very important task). You might also be "excused" if you have already contributed to the public interest in some other way, as per philosopher Jason Brennan's argument in his excellent book The Ethics of Voting. But at least there might be a presumptive obligation to vote here.

Perhaps you also have a duty to become a well-informed and unbiased voter in the first place. But that requires a lot of time and effort, and may be especially difficult in a world where government policy extends to so many issues, thereby requiring extensive knowledge to understand more than a small fraction of them. It's hard to justify the idea that we have a duty to devote that much time to politics. It's certainly a far cry from the initial intuitive scenario where you have a duty to help Gandalf defeat Sauron, because all you need do is check the right box on a ballot.

To sum up, there can potentially be a duty to vote in a situation where 1) there is a big difference between the two sides, 2) your vote has a significant chance of being decisive, and 3) you have good reason to think you are right about which candidate is best (or at least to conclude that your reasoning is better than than that of the average voter). In that world, you also have a duty to avoid voting for the "bad" candidate. If you have an inclination to do the latter, it is better for you to abstain than to vote.

But these circumstances apply to a relatively small subset of voting decisions. In most elections, the differences between candidates are not as great, there is more uncertainty about which one is better, and a high percentage of the potential electorate have good reason to doubt the quality of their judgment.

The absence of a moral duty to vote in a given election doesn't necessarily mean you should abstain. Unless you have a moral duty not to vote (as in the Sauron supporter case discussed above), then you can vote or note vote without fear of condemnation. In my view, you do have at least a presumptive obligation to become relatively informed if you do choose to vote. But that's different from having an obligation to vote, as such.

Neither the duty to vote (where it exists) nor the duty to abstain (where that exists) are ones that should be enforced by the government. I oppose mandatory voting, and I am also skeptical that the government can be trusted to discern who is likely to be a good voter and who isn't, beyond perhaps some very minimal standards. These are moral obligations that individual voters should fulfill of their own accord, though we know many may fail to do so.

If this state of affairs seems unsatisfying, then I would suggest it strengthens the case for systemic reform to reduce our reliance on the knowledge and insight of voters, who often have strong incentives to be ignorant and biased in their judgments. I discuss potential options in my book Democracy and Political Ignorance, and here. In my most recent work, I describe how we can empower people to have greater control over the policies they live under by expanding opportunities for them to "vote with their feet."

In the meantime, we should take seriously the possibility that there is sometimes a duty to vote to defeat a (great enough) evil. But we should also recognize the limits of such claims.

UPDATE: In this 2014 post, I criticized the related oft-heard claim that "if you don't vote, you have no right to complain."

Show Comments (67)