The Volokh Conspiracy

Mostly law professors | Sometimes contrarian | Often libertarian | Always independent

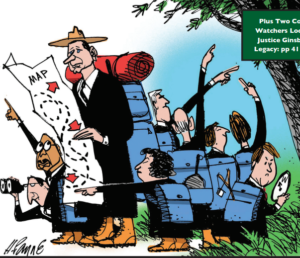

Environmental Law in the Roberts Court

The Supreme Court decides a decent number of environmental cases, but does not seem particularly interested in environmental concerns.

Environmental law constitutes a decent sliver of the Supreme Court's caseload, but none of the current justices seems to have much interest in environmental law, as such -- or so I argue in my new article, "Which Way for the Roberts Court?", the cover story for the November/December 2020 issue of The Environmental Forum, published by the Environmental Law Institute.

Here is a taste of the article:

In many respects, the 2019-20 Supreme Court term encapsulates the Roberts Court's treatment of environmental issues. In a majority of cases, the position supported by environmental groups fails. On the other hand, positions favored by business groups

or the federal government tend to succeed. Looking behind the numbers, however, reveals two equally important tendencies. First, the Court seems to lack much interest in the distinct environmental content of environmental law cases. Second, the justices do not perceive environmental law as uniquely distinct or even important. Nonetheless, the most significant and far-reaching environmental law cases before the Court have been the ones in which environmentalist groups have been most likely to prevail. One question is whether this pattern will hold once a new justice replaces the late Ruth Bader Ginsburg on the Court. . . .The substance of the Court's environmental law decisions confirms what the language of the opinions would suggest: The Court does not really view environmental law cases as environmental cases. That is, the Court does not view environmental law as a distinct field of law, nor do the justices evince any recognition that environmental questions may require viewing traditional doctrines through a green lens. The Roberts Court, like its immediate predecessors, has shown little affinity for ecological values or the idea than environmental law is a distinct area of law raising distinct concerns.

The justices tend to focus on the underlying legal questions, not the ecological concerns that may have led policymakers to adopt a given regulation or environmental groups to file suit. If the case involves how a statute should be interpreted, the justices will focus on statutory interpretation. If it centers on a question of administrative procedure, then the justice's respective doctrinal commitments on questions of administrative law will drive the decision. And so on. Ecological considerations are, at best, window dressing, and do not provide the rules of decision. The justices are more concerned about how to read a statute or limits on federal regulatory authority, writ large, than they are on the ecological dimensions of their decisions. This creates challenges to environmental advocates but it may also create opportunities.

The article was largely completed before Justice Ginsburg's passing, but I think the underlying thesis holds. Her death does not affect my assessment of the past fifteen years, but her potential replacement could definitely affect the course of environmental law at the Supreme Court in the future.

The full cover package includes a few sidebars by Professors Lisa Heinzerling, Robert Percival, and Amanda Leiter, providing additional perspectives on environmental law on the Court, and Justice Ginsburg's environmental law legacy.

Editor's Note: We invite comments and request that they be civil and on-topic. We do not moderate or assume any responsibility for comments, which are owned by the readers who post them. Comments do not represent the views of Reason.com or Reason Foundation. We reserve the right to delete any comment for any reason at any time. Comments may only be edited within 5 minutes of posting. Report abuses.

Please to post comments

"That is, the Court does not view environmental law as a distinct field of law, nor do the justices evince any recognition that environmental questions may require viewing traditional doctrines through a green lens. "

You mean, they're analyzing law as law, and leaving policy choices up to the people charged with writing the laws? How dare they!

Everytime SCOTUS addresses CERCLA, it seems to make things worse. Indeed, last term in the Atlantic Richfield case they could not even agree on the definition of a potential responsible party.

"underlying legal questions, not the ecological concerns"

Puzzling post. I realize it often acts as a super legislature but this is what a court is supposed to do, law, not policy.

I'm sure when Barrett gets on the Court her outlook will be infectious.

Maybe she will emerge as a leader of the six-justice conservative minority, launching a series of strident dissents that draw cheers at every Federalist Society dinner.

I thought the court was supposed to judge the case presented, according to the law.

Not because they favor business, or disfavor environmental groups....

The justices tend to focus on the underlying legal questions, not the ecological concerns that may have led policymakers to adopt a given regulation or environmental groups to file suit.

Isn't that exactly what we want in the Federal Judiciary? Stick to the law, leave the politics to the politicians.

Many ardent environmentalists are in fact modern Luddites, It's good that Judges focus on the law.

rsteinmetz, are you under the impression that the original Luddites acted in futility, and accomplished little or nothing of value? If so, you need to read up. I suggest, Captain Swing, by historians George Rude and Eric Hobsbawm.

First, the Court seems to lack much interest in the distinct environmental content of environmental law cases. Second, the justices do not perceive environmental law as uniquely distinct or even important.

Completely agree. And what some commenters here seem to miss is that without environmental insight, sometimes legal questions cannot be fairly resolved. For instance, there is no reason why prior to enforcement of a wetlands violation, the EPA should be required to do a time consuming and expensive study to show that land which has in fact been covered in cattails for as long as anyone can remember is in fact a wetland.

"For instance, there is no reason why prior to enforcement of a wetlands violation, the EPA should be required to do a time consuming and expensive study to show that land which has in fact been covered in cattails for as long as anyone can remember is in fact a wetland."

But they certainly should be required to show that it has, in fact, been covered in cattails for as long as anyone can remember.

Not really. If it's covered in cattails now, that should suffice.

Surely the reason is that this is what the applicable law actually says. Or not. But that's the relevant question.

I agree with the folks above (whom I don't normally agree with), and can't see why environmental law should be viewed with some sort of green-colored glasses.

Where we differ is that I think we should have robust (constitutionally compliant) environmental law.

apedad, are you similarly unsympathetic to the notion of Law and Economics? No substantive economic insights ought to color the outcomes of cases affecting economic policy?

If this is true, then it is sad. Looking at the dry words of the law, not understanding ecology and not wanting to help her is strange. You always have to look at the whole picture of what is happening. When my friend had problems, he was helped here