The Volokh Conspiracy

Mostly law professors | Sometimes contrarian | Often libertarian | Always independent

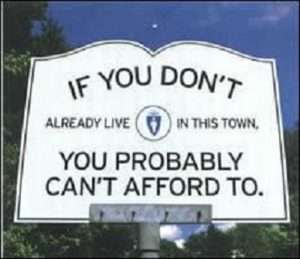

Progress on Exclusionary Zoning, Regression on Rent Control

Many jurisdictions are alleviating housing shortgages by cutting back on zoning. Unfortunately, there is also a trend towards expanding rent control, which is likely to have the opposite effect.

Housing shortages caused by harmful government policy are a serious problem in many parts of the United States. The good news on this front is that many jurisdictions are making progress towards easing zoning restrictions that are the principal culprit behind many such shortages. After years of seeming stagnation, zoning reform is hot. The bad news, however, is that rent control is also gaining momentum. Even as zoning reform helps alleviate housing shortages, rent control is likely to make them worse.

At this time last year, I wrote about the growing momentum for cutting back on exclusionary in various parts of the country. That trend has continued in 2019. In July, the Oregon state legislature passed a law banning single-family home zoning requirements throughout most of the state, thereby enabling construction of multifamily housing in many areas where there are severe shortages. The city of Seattle has also made some progress here.

The Democratic takeover of the Virginia state legislature in November has led to consideration of a major zoning reform law in my home state. If it passes, it would legalize construction of duplex housing in any part of the state currently zoned for single-family homes, thereby expanding housing availability in the the increasingly expensive northern Virginia region. Other jurisdictions are also considering similar reforms.

A major reform bill stalled for a second time in the California state legislature earlier this year. But the very fact it had a real chance of success bodes well for the future, in a state that has some of the nation's most severe housing shortages.

These and other recent zoning reforms have mostly been passed in jurisdictions dominated by liberal Democrats. The political left has begun to take notice of and act on the broad agreement among policy experts that zoning is a major obstacle to affordable housing, and also excludes millions of people from job opportunities. Zoning thereby harm both the excluded workers themselves and the broader economy, which loses the additional productivity they would have provided.

If zoning restrictions make it difficult or impossible to build new housing in response to rising demand, basic economics 101 indicates that prices will go up, and many will be priced out of the relevant market. By contrast, the experience of cities like Houston shows that developers are more than capable of keeping up with rapid growth if they are allowed to build.

Part of the reason why recent zoning reform efforts have been led by liberals is that liberal jurisdictions tend to have the most onerous zoning regulations in the first place. Still, credit should be given where credit is due. Many on the left are making a real effort to clean up this awful mess.

Republicans, by contrast, have often been on the wrong side of the issue lately, despite the near-universal criticism of zoning by free market economists and housing specialists. For example, the Oregon GOP opposed the recent zoning reform in that state. Some on the right oppose it based on fear that it might "urbanize" suburbs and allow more poor people to move there. On the other hand, Trump administration Housing and Urban Development Secretary Ben Carson - whom I'm no fan of on many other issues - deserves credit for his strong advocacy of cutting back zoning.

While the struggle is far from over, there can be little doubt that we are making progress on the zoning front. That is excellent news.

Unfortunately, the good news on zoning is coupled with bad news on rent control. The same Democratic-controlled Oregon state legislature that recently passed a strong zoning reform bill also enacted a sweeping rent control law earlier this year. California and New York has also enacted major new expansions of rent control this year. After a long period during which rent control seemed largely moribund, it has once again become a major cause of much of the political left. Bernie Sanders, the favorite presidential candidate of the growing "democratic socialist" wing of the left, has even called for the enactment of a national rent control law.

The expert consensus against rent control is at least as broad as that in favor of zoning reform. Economists across the political spectrum overwhelmingly oppose it. Expert critics of rent control range from the very liberal Paul Krugman on the left to Thomas Sowell on the right. The issue is often used in introductory economics classes as an example of a question on which nearly all economists can agree.

That consensus arises from the simple point that, if landlords cannot raise rent in response to growing demand, they are likely to put fewer rental properties on the market. For similar reasons, rent control is likely to reduce new construction in high-demand areas, and also lead to worse maintenance of existing properties. Real-world evidence backs up these theoretical predictions. Stanford economist Rebecca Diamond summed up the results of recent studies on the subject in an article published by the liberal Brookings Institution last year:

Rent control appears to help affordability in the short run for current tenants, but in the long-run decreases affordability, fuels gentrification, and creates negative externalities on the surrounding neighborhood. These results highlight that forcing landlords to provide insurance to tenants against rent increases can ultimately be counterproductive.

While current tenants get a windfall (at least in the short run), rent control reduces the availability of housing for everyone else, and also reduces economic growth by excluding people from areas where they could find new job opportunities and become more productive. Its effects are actually similar to those of exclusionary zoning. Thus, regression on the rent control front could well offset some of the progress being made on the zoning front, especially in cases - like Oregon - where the same jurisdiction pursues both agendas, despite the contradiction between them.

In addition to having opposite effects on housing shortages, zoning reform and rent control are also based on opposing assumptions about the way housing markets work. The former relies on the assumption that increasing demand will lead to increasing supply, so long as the government allows new construction to occur. In short, market incentives work. Increases in demand lead to increases in price, which in turn incentivizes new production, thereby alleviating shortages and - eventually -reducing prices.

By contrast, rent control implicitly assumes that landlords and developers will not cut back on the quantity and quality of housing, even if prices are artificially lowered by government intervention. For this to work, either market participants must be irrationally indifferent to prices and profits, or there must be some sort of unusual market failure that makes supply insensitive to demand. Neither scenario is plausible. The many liberal Democrats who oppose exclusionary zoning while simultaneously favoring rent control are implicitly making self-contradictory economic assumptions. In one area, they accept basic Economics 101; in the other, they utterly reject it.

I am tempted to say that simultaneous revival of zoning reform and rent control is a prototypical example of the left hand undermining what the right hand is doing. But, in this case, it is really the left hand working at cross-purposes with itself, since it is the political left that has been the biggest driving force behind both developments. Hopefully, they will resolve the inconsistency in the direction of embracing good economics across the board. That means opposing both rent control and exclusionary zoning.

UPDATE: Matthew Yglesias has a valuable article on the emerging politics of zoning at Vox, here, which came out a couple days after this post.

Editor's Note: We invite comments and request that they be civil and on-topic. We do not moderate or assume any responsibility for comments, which are owned by the readers who post them. Comments do not represent the views of Reason.com or Reason Foundation. We reserve the right to delete any comment for any reason at any time. Comments may only be edited within 5 minutes of posting. Report abuses.

Please to post comments

Rent control really is silly.

Among other things, it really doesn't hold down rents very well. Poor maintenance decreases the value of the property, so rents in terms of value received go up.

Those lucky enough to have a nice controlled apartment are reluctant to move, so newcomers end up paying more because supply is restricted. That also reduces vacancies enough that finding an apartment is hard. Potential tenants end up spending more time than normal to find a place, and sometimes paying only slightly concealed bribes to agents.

Caveat: I'm opposed to rent control.

That being said, rent control does have some benefits, especially politically, and especially initially. In a tight housing market, where rents are seeing regular, high increases, it does act as a short term halt on rent increases, at least for a certain percentage of people. It's basically a form of price control, and in limited circumstances, price controls have value for the government, in limiting inflation and ensuring stability (it's a short term fix, with dramatic long term consequences, but in the short term, it does work)

Politically, rent control is much more of a winner. First, it looks as if the politicians are "doing something about the problem". Secondly, and potentially a more valuable resource, rent control creates a subset of very invested residents who like rent control and are motivated to keep it. Those people who can't move in because they don't rent control....well, they don't vote in that city/district, now do they?

Rent control does not fight inflation

Whatever short-term benefits may exist, rent control has the problem you describe - it "creates a subset of very invested residents who like rent control and are motivated to keep it," so any hope that it will be a short-term measure is likely to prove vain.

In the short term, in a limited fashion, in certain circumstances, rent control can fight inflation, as can other price controls.

Housing is a commodity with a relatively long production time. Thus increases in supply will typically lag increases in demand.

We can imagine a situation in which rent increases are going up at a very large rate (>10% a year for example...or >10% a month). This would require salary increases to also go up, thus ultimately leading to inflation. In such a situation temporary rent controls would help halt inflation, while supply can have the opportunity to increase.

There is also a socio-political value to short term controls on prices and rents. Emphasis on short term.

In the long term, of course, these benefits are by far overwhelmed by the distortion to the supply and demand curves, which limit incentives to increase supply.

A.L.,

Controlling one set of prices does not limit the overall price level in an economy. Rent control does not reduce demand.

Prices elsewhere rise. If your rent were miraculously cut in half, you would likely start spending more on other things.

Right; the mistake in his thinking is talking about rent as if it were some autonomous force. Rents do not just spontaneously increase; they increase because demand has increased.

1. "Controlling one set of prices does not limit the overall price level in an economy."

The overall price level in an economy is the combination of the price levels for each individual item. If an item which takes a major part of the budget for an average family is controlled, then the overall price level has a component of it controlled.

2. "Rent control does not reduce demand"

You are correct, it does not. If anything, it increases demand.

3. Prices elsewhere rise. If your rent were miraculously cut in half, you would likely start spending more on other things

So, "likely" is holding a lot of the burden here. But, let's assign a probability here. Of the 50% savings in your rent, you immediately spend half of it. But you save the other half. So, prices are limited in their increase there by that 1/2 of rent savings, and the other 1/2 isn't automatically spent.

"If an item which takes a major part of the budget for an average family is controlled, then the overall price level has a component of it controlled."

Not if the family spends the money on something else. Even if the family saves the money, that money goes to goods and services, in the form of direct spending on financial advisers, increased lending by the saver's bank, etc.

There are two causes of inflation, increased costs (cost-push) and increased demand (demand-pull). Rent control does not increase the cost of producing housing. And while rent control does increase the relative demand for housing, it controls the price for that specific good, so it shouldn't have an inflationary effect on housing prices.*

*Near-term. Rent control does increase the cost of housing. It also can cause near-term inflation in jurisdictions, like Oregon, that have tenancy rent control, caps on rent increases for existing but not new renters. First, it encouraged lessors to increase rents near-term to get in before the law takes effect. Second, for new rentals, the landlord will bias towards profiling towards shorter-term renters who may be willing to spend more (for a short-term lease) than people seeking long-term rentals. The effect of this might be small, but will increase housing costs near-term.

"Not if the family spends the money on something else"

Again, if is pulling a lot here. And you're asking the each family to ALWAYS spend ALL of the additional funding.

If just some of the families save the money instead, that money does not directly contribute to inflation, as its velocity is slowed.

The "velocity" of money is irrelevant to inflation at the "overall price level in an economy". "save the money instead" is a good/service, with a price.

The velocity of money is critical to inflation.

Barring lawyer's activities in some areas, such as commenting on rent control, does have short term benefits to other commenters and in not allowing armchair lawyers to waste billable time on non-billable activity.

Failing to properly describe and understand the arguments on the other side of any policy you don't agree with is problematic. Resorting to insults is worse.

Some arguments are so weak that sneering at them is the only appropriate response.

How about you define some terms? What length of the initial period do you accept as beneficial for rent control? What measurements would you use to quantify that? How do you recognize the flip from beneficial to harmful, or do you just declare some arbitrary duration and never validate it? Can you cite any historical examples of this initial beneficial phases flipping to harmful, and how do you recognize them?

Here's some reading for you.

https://www.diw.de/de/diw_01.c.578224.de/themen_nachrichten/mietpreisbremse_ist_besser_als_ihr_ruf_kann_wohnungsmarktproblem_aber_nicht_allein_loesen.html

For Pete's sake! If you can't be bothered to paraphrase them in an English language comment, I can't be bothered to slog through some google translation from German.

After your initial disrespectful comment, you asked a series of very involved questions, including "Can you cite any historical examples..."

Which I responded to with an actual cite, and a full paper. And you can't be bothered to read it and actually understand the answers to some of your very involved questions?

One might think that you're not being serious in your questions...

One might think you had no principles and believed only in the subjective rule of men.

A.L.,

Sehr interessant.

Danke.

ihr willkommen

I don't know if the societal equivalent of a disease, a chronic process leading to the degradation of the organism, is properly described as a benefit.

I speak of the political benefit aka winning an election as benefit.

Homes are expensive because we are overpopulated. If zoning were responsible, homes would have been expensive in the 40s 50s and 60s - we had exclusionary zoning then but homes were affordable. Why? Look at the US population 25 to 34 for 1930, 40, 50, 60 and 70 - flat. Look at 1980.

Hos is it that there is so much dishonest pseudo analysis of issues? Oh . . . right.

Right; there's lots of rent-seeking (pun intended) and economic waste. Beneficiaries of rent control are sometimes incentivized to monetize their lucky status by illegally subletting their below-market places; landlords then spend time and money trying to catch them, or to find other ways to get rid of rent-control tenants.

I think a lot of rent control proponents literally don't comprehend the idea of rent control has been around probably thousands of years and has been tried thousands of times.

Housing shortages caused by harmful government policy are a serious problem in many parts of the United States.

Yeah, imagine what housing prices and rents would look like if the US had thirty to fifty million fewer immigrants.

By that same logic, lets do a One Child Policy - think of the housing!

That's logic only if you ignore rights; "You think the Salvation Army does good? By the same logic, let's just rob people and use the money to help the poor!" It ignores that restrictive immigration laws violate no one's rights, because potential immigrants have no right to come here, while One Child policies violate well established rights.

Restrictive immigration laws burden the right to travel.

And in practice, they can lead to outcomes like family separation, kids in cages, and lots of illegal searches, which violate other rights as well.

The "right to travel"?

I wasn't aware there was such a right to international travel.

If there's a right to travel, maybe the west should get back into the business of imperialism and squashing local governments and setting up more open, less corrupt places. It could be tough, but you know, right to travel (and right to free people from dictatorship AKA large-scale hostage situations.)

Nah.

Sure there is a right to travel. That;s why there are no street theater security lines at the airports, and plenty of free parking at all times.

There are cases on that. Look them up.

Well, if you mean the state department can cancel passports based on certain conduct, sure.

But actually, there are a number of international conventions that do guarantee rights to cross borders under various circumstances, so yes, there's a right to travel.

"under various circumstances"

Under very limited circumstances. There's no broad "right to travel" to any country you want for as long as you want, whenever you want. There's a limited right in the UN declaration of human rights to LEAVE your country and to return to your country. But not to travel to any other country you want.

There is a broad right to travel international waters, though. We send out the Navy from time to time to reinforce this right.

If they stay out of our country, they won't be separated.

Yeah, Milo's argument ignores a whole bunch of things, both moral and practical, that immigration gives us.

It's that kind of one-sided logic that can be used to rationalize all sorts of horrid policies. Including his own myopic anti-immigration rant.

I just saw Catch-22 over the holiday. The real Milo would be ashamed.

The simple fact is that the choice to have children is a universally recognized basic human right.

There is no human right to cross borders into a country you are not a citizen of. None.

Your arbitrary weighing of the real rights and the others is both not how rights work and doesn't matter.

Milo's dumb anti-immigrant point made no allowances for any moral costs on the other side at all.

Look, you keep talking about “real rights” and “moral costs”. I don’t recognize them, neither did the authors of the US Constitutions, the authors of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, or any other institution I know of. If you want others to recognize such rights, you need to make a convincing argument for them, and so far, you have failed to do so.

They violate my right to do business with whom I choose.

I don't know of anybody who recognizes such a positive right; where do you think it comes from?

All libertarianism recognizes is that you should be free from state interference in your associations (business or personal) with people you can actually associate with.

I wasn't describing a positive right. If you'd prefer me to rephrase it as violating my right not to have the government prevent me from doing business with whom I choose (assuming, of course, that they consent), fine.

Restrictive immigration laws constitute state interference in my associations (business and personal).

So does national sovereignty, are you opposed to that?

Yes, these liberal traitors are opposed to that.

Yes, you were describing a positive right. Negative rights are described in terms of government powers.

(1) Government should not have the power to interfere in your business transactions.

(2) Government should (and does) have the power to enforce national borders.

There is no conflict between those two powers; only by rephrasing (1) as an unlimited, absolute positive right (as you do) do you create the appearance of a conflict.

Another way of putting it is that government power (1) (like any government power) might be clarified as:

(1) Government should not have the power to interfere in your business transactions [except as a consequence of other legitimate powers granted to government]

The One Child policy is incompatible with human rights. Furthermore, children born to Americans who have been in the US for several generations tend to do well.

Restrictions on illegal and legal (im)migration are completely in accordance with human rights as recognized by the UN, by the US Constitution, by the EU, and by European nations.

So, yes, we should do what we can do in accordance with human rights, namely restrict illegal migration of low skill, unproductive workers, in order to improve the situation of low income Americans.

It was an anti-immigrant statement; full spectrum. Don't try and defend that kind of nativist trash talk by adding in codicils and other arguments as though they were implied. You will not save the childishness on display.

No, it was a factual statement: with 30-50 million fewer immigrants, housing prices in the US would be much lower, since much of the rise in housing prices is due to immigrants moving to cities.

People like you make any rational discussion of immigration and housing policy impossible.

Furthermore, children born to Americans who have been in the US for several generations tend to do well.

Like Stephen Colbert, you don't see color.

Like Stephen Colbert, you are a blithering idiot.

Leaving your numbers aside, I'd say housing prices would be higher if we cut back on immigration.

Lots of immigrants work in construction and associated trades.

Kind of a wash, I'd think. Less supply, less demand,

The thing is, high illegal immigration might drive down costs by lowering wages, but it lowers the wages, which means many people not being able to afford even the lowered price.

Why is it "kind of a wash?" Have you made any effort to estimate the numbers?

How many hours of labor per unit does it take to build an apartment building? How long does it last?

Just imagine how worse off our economy would be with “30 to 50 million fewer immigrants.”.

Yeah, if you worship GDP, then I guess you are right. If you are concerned with GDP per capita, than not so much. And if you care about affordable family formation for US citizens, then you are dead wrong.

GDP per capita is not a good measure. We don't care if it falls, so long as the GDP, or rather income, of the non-immigrants doesn't fall.

Yeah as long as Bloomberg, Bezos, Zuckerberg and the Kochs are doing well enough to pull up the average, who cares about the working and middle class?

If those losers actually had something to contribute to this country they'd be billionaires, too.

Your assumption about what immigration does to the working and middle class is basically unsupported by just about any economist you would care to speak to.

As is your conflation with being rich and having something to contribute to society.

The rich are not our betters, Milo.

That's absolutely false, for the simple reason that politics and political power is driven by the totality of people in a country, not just the non-immigrants.

Per capita GDP determines both the quality of life for most people and the political stability and liberties in a country. The lower per capita gets, the more political stability and liberty are at risk.

Ah. You care so much about our immigrant population you want to lower it.

Somehow I don't think that's actually your logic.

I don’t want to “lower the immigrant population”. I think immigrants should stay in the country.

I want people in the country illegally to be deported, and I want future immigration limited to people with above average skills and incomes. That’s my logic. That benefits both Americans and immigrants.

Being an immigrant myself, the last thing I want is for the US to be overrun by the very people I tried to get away from when emigrating.

That makes zero sense.

Care to rephrase?

To rephrase it, I have to understand what concept you are having trouble with.

I mean, is it too hard for you to understand that people in Luxembourg are better off and more free than people in Russia, even though both the total GDP and the number of rich people in Russia are higher?

I agree with Somin on the zoning issue. But the rent control issue is actually more complicated. Let me explain.

First of all, when it comes to "economics 101" to analyze the world, it is important to realize that there are two factors at play. The direction of an effect, and the magnitude of the effect. All economics 101 tells you is the direction of the effect, but it does not tell you the magnitude.

Take minimum wage for example. If you raise wages with a wage floor, the quantity of labor demanded should decrease. Or so goes the economics 101 argument.

But, out here in the real world, this effect hasn't appeared to be a strong one at the minimum wage levels now in place. It is not that economics 101 is wrong; it is that magnitude matters more than direction.

Somin laments rent control. But, depending on how it is implemented, it isn't going to have much effect on the decisions of investors.

Think about it from an investor perspective. For an investor, early returns matter much more than later returns (due to the time value of money). So, if rent control only kicks in after the property has been on the market for 10 or 20 years, it isn't likely to play a very big role in the NPV analysis of the project.

Second, a sort of rent control that allows investors to only raise rents by a certain "reasonable percentage" per year at maximum has positive externalities in the form of increased stability for tenants, who can better plan for the future. (I call it an externality even though tenants are part of the contract, because I do not believe that tenants can, as a practical matter, negotiate for this outcome.) Again, as long as you do not restrict the amount of initial rent that can be charged (but only regulate the increases), this isn't going to affect the NPV of new development very much.

Third, there is a political economy argument for this sort of control. Namely, combatting NIMBYism. Incumbent property owners, to the extent that they are receiving rental income, would like that rental income to increase without having to make any additional investments. One way to achieve this is to prevent new development. By putting controls on the ability to increase existing rents, we greatly limit this incentive. A property owner who wishes to receive more rental income will have to invest in building rather than investing in the obstructing of building.

So, if you actually think deeper about the topic, returning economics from a view of discrete transactions to a broader view of political economy, rent control could actually be part of the formula for ensuring greater housing and combatting excessive zoning and other government restrictions on housing development.

The problems are: (1) it screws over, big time, anyone who wants to move in, and that's discriminatory- there's no reason people who get somewhere first should get to pull up the welcome mat- and (2) over time, it creates terrible conditions in housing, because there is little incentive to fix property.

Also, in practice, your "no NIMBYs" doesn't hold true. Rent controlled cities are full of NIMBYs, which makes rent control so much worse.

I don't think that people who want to move in are "screwed over" if they can't displace existing residents by outbidding them. I think reliance interests in a community are important. For example, children develop friendships at schools and people develop relationships in the community. The value of these things are not considered in the "auction" since they can't be monetized and sold.

The thing that is "screwing over" the person who would like to move to the community is not the renter who is embedded in the community and has roots in the community, but the lack of development. Which we can address by eliminating zoning regulations and other building restrictions that prevent more housing from being built.

As far as maintenance of the property goes, you can address that with building codes that require habitability. You could also address it with a tenant cooperative which, if organized, could take over maintenance and deduct the fair market value from rent. Of course, most tenants would not want to form a cooperative and most landlords would not want them to form one. But the possibility of one being formed would create an incentive for the owner to perform reasonable maintenance.

It is true that rent controlled cities are full of NIMBYs, but there is much less financial incentive to be a NIMBY if it is difficult to transform the fruits of NIMBY activism into rental income.

For example, children develop friendships at schools and people develop relationships in the community. The value of these things are not considered in the “auction” since they can’t be monetized and sold.

Of course they are. If the rent goes up the tenant will consider these things in deciding whether to stay or move.

As far as maintenance of the property goes, you can address that with building codes that require habitability. You could also address it with a tenant cooperative which, if organized, could take over maintenance and deduct the fair market value from rent. Of course, most tenants would not want to form a cooperative and most landlords would not want them to form one. But the possibility of one being formed would create an incentive for the owner to perform reasonable maintenance.

I don't think reality supports these arguments, plus there is a gap between "habitable" and pleasant. A building with unpainted walls, worn carpet, poorly functioning elevators, and hallway lights out is habitable.

Sure, the tenant will consider the value of these things when deciding whether and how much to bid in the "auction". But only if they are able.

However, since the tenant cannot sell these things, if they aren't able to "defend" their position in an auction due to liquidity constraints, they will be displaced. Even if they are, in fact, the highest value user of the property due to the value of those relationship. This will result in a suboptimal economic misallocation.

"I don’t think reality supports these arguments, plus there is a gap between “habitable” and pleasant. A building with unpainted walls, worn carpet, poorly functioning elevators, and hallway lights out is habitable."

Tenants that want these things badly enough could band together and pay for them out of their own pocket. There really is no reason, in principle, that all good things enjoyed by tenants must be paid for by the landlord.

"Even if they are, in fact, the highest value user of the property due to the value of those relationship. This will result in a suboptimal economic misallocation."

The economic allocation is the person willing to spend the most on the good gets it. That's a feature, not a bug. Since that's the only way we know how to measure the "value" you're talking about.

"There really is no reason, in principle, that all good things enjoyed by tenants must be paid for by the landlord."

And that's why rent control can't work. The landlord just shifts costs back to the tenant.

No, the economic allocation is that the person who values the thing most gets it. There is no way to exactly measure the value I am talking about, but the only reason we would even care about economic allocative efficiency at all is because we believe that goods will tend to go to those who value them most. To the extent this doesn't happen, we don't care about economic allocative efficiency, because it is meaningless. So, although "value" can't be directly measured, it is still what is important. You are free to substitute some other thing you think is important if you like, and we can argue about whether it is a better measure, but you should be explicit about it.

To put it another way, if we are going to use the word "efficiency" we have to say with respect to what goal (aka objective function). Efficiency cannot be measured without an objective function. But there are an infinite number of objective functions.

"And that’s why rent control can’t work. The landlord just shifts costs back to the tenant."

But it does work. Because the landlord cannot shift ALL costs to the tenant. The landlord has duties to maintain habitability that cannot be shifted to the tenant.

And we aren't just talking about costs, we are also talking about future benefits. When a tenant invests in living in a certain place for a long period of time, can that investment (the future benefits that would otherwise accrue to the tenant based on the decision to live in a particular area over a period of time, be immediately eliminated by the landlord? Rent control protects that investment and "works" to the extent that you think that investment should be protected. It also obviously has many other effects.

More generally, talking about whether something "works" or not tends to be imprecise. Because it immediately bring to mind to questions. "Works for whom?" and "Works for what purpose?" It is better to talk about the concrete effects of a policy and then talk about for what purposes the policy works and for what purposes it doesn't and with respect to which people.

Tenants that want these things badly enough could band together and pay for them out of their own pocket.

This is silly.

First, as a practical matter, it's going to be impossible for any significant number of tenants to agree on what to buy, how much to spend, who to hire to do the work, what color to paint the walls, etc. An apartment building is not a condominium. The tenants don't join an association with specified governance rules when they sign a lease. There is nothing to force them to contribute to your cooperative.

Second, why should tenants be required to pay for capital improvements? They will only enjoy them while they live in the building, and the landlord will own them.

Look, part of the function of a landlord is to provide capital - pay for the building and improvements, etc. Another part is to do what the association does in a condo or coop building - manage the property, maintain it, etc. All that is what tenants are paying for.

And the arrangement makes perfect sense and is quite efficient. You can live in a nice place by renting, without having to bear the cost and hassle of owning. The landlord does all that.

I don’t think that people who want to move in are “screwed over” if they can’t displace existing residents by outbidding them. I think reliance interests in a community are important.

A lot of white people felt that way about blacks moving into their neighborhoods.

I am dead serious about this. "Community" as an excuse to exclude outsiders is evil. Evil. The worst kind of bigotry. "I got mine" selfishness.

Screw community. I want people to be able to share in the bounty. People who want to keep outsiders out can go screw themselves with a barbed sex toy.

I am not talking about keeping outsiders out. I am talking about being able to stay where you are without being outbid by an outsider, forced to lose all the relationships in the community that you spent years developing.

That sort of stability is worth protecting. I think we should try to accommodate newcomers by building new housing, not forcing lower income people to move.

Sometimes in life, you have to move. Living somewhere does not give one priority over others who might want to live there too.

Maybe if more people were exposed to higher rents there might be a constituency to relax zoning and pay for kore housing.

"Sometimes in life, you have to move. Living somewhere does not give one priority over others who might want to live there too."

Sometimes in life, you can't move in. You wanting to live somewhere does not give you priority over those who already do.

Your argument hasn't gotten you anywhere yet.

"Maybe if more people were exposed to higher rents there might be a constituency to relax zoning and pay for more housing."

Or maybe it is precisely the higher rents that are rewarding NIMBYs for their NIMBYism. A person who is kicked out of a community due to their inability to continue to afford rent certainly will not be voting in that community any longer, so I am not sure how displacement could possible create a "constituency" unless you mean at the state rather than local level. And what will this constituency likely demand? I think one thing they will demand is rent control.

Rent control and anti-NIMBYism go together, since rent control limits the incentive to advocate for restrictive zoning and other building restrictions.

Rent control and pro-NIMBYism go together because both are about keeping outsiders out.

It is more complicated than that.

Alternatively, lack of rent control provides a financial incentive for NIMBYism, so they are in tension.

"I don’t think that people who want to move in are “screwed over” if they can’t displace existing residents by outbidding them."

Rent control prohibits them from outbidding existing residents. That's the unfairness.

"The value of these things are not considered in the “auction” since they can’t be monetized and sold."

These things are considered in the auction. If keeping my children in a local school is important to me, I price that into renting or buying in the area that allows my children in the local school.

What is unfair about it?

Let us say that X can't outbid Y to live in some property Z.

Why should a neutral observer of this situation who is completely impartial as far as X and Y go think that it is unfair to X that they can't outbid Y? (And yes, I am setting you up. To answer this question, I think you are going to have to concede something.)

"These things are considered in the auction. If keeping my children in a local school is important to me, I price that into renting or buying in the area that allows my children in the local school."

They are considered in an auction, but not if liquidity constraints prevent you from defending your interest to keep your children in the same school with the same friends.

It's unfair because there's no reason incumbency should buy you the right to keep someone else out.

Counter point: There is no reason that money should buy you the right to destroy the relationships and physical presence that a person with less income has built over a period of many years.

"Why should a neutral observer of this situation who is completely impartial as far as X and Y go think that it is unfair to X that they can’t outbid Y?"

Because the neutral observer wants the finite resource to go to the person who wants it the most, and the bid is how we measure want. If X wants access to the neighborhood more than Y does, then the extent of benefit that X gets out of living in the neighborhood is greater than the harm Y suffers by being moved out. Since this is a net gain in terms of human happiness, it's a more efficient result than allowing Y to stay and keeping X out.

"They are considered in an auction, but not if liquidity constraints prevent you from defending your interest to keep your children in the same school with the same friends."

If the choice is between "liquidity constraints" preventing someone from staying in a school they want to stay in or government intervention preventing an outsider from moving their children to the new school, why does the neutral observer care about the former? The liquidity constraints apply equally to people in and outside the neighborhood. It's a morally irrelevant factor.

"If keeping my children in a local school is important to me, I price that into renting or buying in the area that allows my children in the local school."

Someone needs a refresher on sunk costs fallacy.

For an investor, early returns matter much more than later returns (due to the time value of money). So, if rent control only kicks in after the property has been on the market for 10 or 20 years, it isn’t likely to play a very big role in the NPV analysis of the project.

The actual value of the property in the future is very important to the owner, if for no other reason than they might want to sell it. Delayed rent control affects that dramatically.

Again, as long as you do not restrict the amount of initial rent that can be charged (but only regulate the increases), this isn’t going to affect the NPV of new development very much.

If you do that you are going to drive up the initial rents, making housing more expensive.

By putting controls on the ability to increase existing rents, we greatly limit this incentive. A property owner who wishes to receive more rental income will have to invest in building rather than investing in the obstructing of building.

I don't buy this at all. It seems to me that the property owner will simply invest elsewhere.

Est. $700,000 per unit for cheapass homeless housing in SF, once regulations and lawsuits got done with it.

One of the main economic problems in unfree societies is the corruption, which adds kickbacks to get anything done, which leads to people saying screw it on investments, so the economies are sick wheezers.

Here we effectively ape it via regulation.

I agree. Excessive regulation, and especially, excessive delay are huge problems. We ought to be encouraging (maybe even subsidizing) developers who want to build housing, not making it a nightmare to even try.

You could leave out the developers, and develop the property directly, rather than subsidize it. People flock to public housing, right?

I am not a fan of public housing.

The claim is not that the future value of the property is unimportant. The claim is that $100 received today is more valuable than $100 received 10 years from now. Rent control that kicks in later (after investors have been able to achieve a strong NPV on their investment) will not significantly impede the incentive to invest.

"If you do that you are going to drive up the initial rents, making housing more expensive."

This would be true IF landlords naturally included the value of windfalls from unexpected rent increases when performing NPV calculations. But, a good portion of these rent increases are opportunistic (not anticipated when initially deciding whether to move forward with the project). To the extent they are merely opportunistic windfalls, not providing them will not have any impact on either price, or the quality of amenities provided.

A ceiling on rent increases is something that investors can handle easily. They can plug that number into their analysis and make a rational decision to go forward or not.

Overall, you are right about the direction of the effect. Certainly, a limit on increasing rent is going to decrease the NPV of a project. But, the impact will tend to be small.

The ability of a landlord to increase prices is not arbitrary, but is constrained by market forces. So, your idea that landlords will just "increase prices" to make up for it, while true to an extent, is limited.

And tenants get something VERY valuable in exchange for any small rent increases that do occur. Namely, some insurance that if their job situation does not change for the worse, they will be able to continue to live in the neighborhood in the future without being displaced. The value of community relationships is not always properly valued in our economic transactions, but is considerable for those who form important relationships with their neighbors or whose children form relationships. Not to mention continuity of schooling and education. Overall, stability in life tends to have high value in producing thriving individuals.

"I don’t buy this at all. It seems to me that the property owner will simply invest elsewhere."

The property owner would be expected to invest wherever they could get the best return, given their knowledge, aptitudes, and interests.

People who are already landlords tend to be well positioned to scale their operations. They will be encouraged to do so by laws that create rewards for them for scaling their operations and which do not reward them for investing money in NIMBYism in an attempt to maximize revenue at existing properties.

Of course, maybe some will take the money they would have invested in NIMBYism and invest it in the S&P 500 instead of scaling. That is fine. And, in fact, if that is an individuals or firms choice, that is a good sign that they do not believe they are personally in a good position to scale their operations.

David,

The claim is that $100 received today is more valuable than $100 received 10 years from now

But the amount received ten years from now, when the building is sold, is typically a multiple of the rents. It's big enough to make a difference even after allowing for discounting.

And because it depends on rents rent control will have a big effect. If the rents, or expected rents once control kicks in, are 50% less than they would be otherwise the building is worth 50% less.

This would be true IF landlords naturally included the value of windfalls from unexpected rent increases when performing NPV calculations. But, a good portion of these rent increases are opportunistic (not anticipated when initially deciding whether to move forward with the project). To the extent they are merely opportunistic windfalls, not providing them will not have any impact on either price, or the quality of amenities provided.

This is nonsense. Sure, there might be an explosion in RE values somewhere that investors didn't expect, but normal rent increases over time will be built into the landlord's calculations.

People who are already landlords tend to be well positioned to scale their operations. They will be encouraged to do so by laws that create rewards for them for scaling their operations and which do not reward them for investing money in NIMBYism in an attempt to maximize revenue at existing properties.

Even if they want to invest in real estate, because of their expertise, there will be jurisdictions without rent control they can go to.

"But the amount received ten years from now, when the building is sold, is typically a multiple of the rents. It’s big enough to make a difference even after allowing for discounting."

The claim is not that future value doesn't matter. It is that it doesn't matter as much. We are talking about a modest decrease in future value (a smaller income stream 10 or 20 years from now), that when discounted goes from modest to small in PV terms. Now, if you were reducing FV to 0 (as in a perpetuity instead of an annuity), that would be a big change that would matter a lot now. But if you are talking about a modest change in the future, it has a small effect now.

"This is nonsense. Sure, there might be an explosion in RE values somewhere that investors didn’t expect, but normal rent increases over time will be built into the landlord’s calculations."

We actually do not disagree on this at all. "Normal" rent increases are built into the calculation. What isn't built-in are "abnormal" rent increases that could not be anticipated at the time of the investment. Those are just a pure windfall. So, for example, if a new "anti-development" city administration were voted into, and a total moratorium on building new housing and destruction of existing housing massively increased rents, that would just be a windfall, since investors were not counting on this "anti-development" city administration being elected in the future.

"This is nonsense. Sure, there might be an explosion in RE values somewhere that investors didn’t expect, but normal rent increases over time will be built into the landlord’s calculations."

Sure. But if the NPV of a project at their current location is higher, they won't. Furthermore, part of the benefits of scale happen from having properties managed in the same geographic location. Even companies that have properties in many locations tend to have multiple properties in each of those locations for that reason.

Oops, (as in a perpetuity instead of an annuity) should be (as in an annuity instead of a perpetuity).

Geez, this did not go well in terms of copying and pasting. That last paragraph was in response to a different quote, but I copied and pasted the same quote twice. Here is the corrected end of the argument.

"Even if they want to invest in real estate, because of their expertise, there will be jurisdictions without rent control they can go to."

Sure. But if the NPV of a project at their current location is higher, they won’t. Furthermore, part of the benefits of scale happen from having properties managed in the same geographic location. Even companies that have properties in many locations tend to have multiple properties in each of those locations for that reason.

“Normal” rent increases are built into the calculation. What isn’t built-in are “abnormal” rent increases that could not be anticipated at the time of the investment. Those are just a pure windfall.

No.

This is just wrong. You cannot view a specific project in isolation

Risk, in the sense of variability of returns, is an inherent aspect of investing. The investor accepts unanticipated poor returns on some projects, in exchange for unanticipated high returns on others.

"The investor accepts unanticipated poor returns on some projects, in exchange for unanticipated high returns on others."

Yes. As I already mentioned, I do not deny that eliminating completely random windfalls lowers the actual and calculated NPV of the project.

My argument is that these just aren't very important to the NPV overall. Windfalls, positive or negative, are low probability events. So, while putting a ceiling on the positive windfall while not providing a floor on the negative windfall does lower the NPV of the project, the impact is not very significant for two reasons. (1) The importance of the windfall to the NPV has to be multiplied by the low probability of the windfall actually occurring. (2) And then further multiplied by the factor in play for the time value of money.

Here is a concrete calculation for you.

Imagine 10 years from now, there is a probability p of windfall with magnitude M. But, you can't capture the whole windfall, because the amount you can increase rent is capped. So, let's say that you can capture N, where N <= M.

The expected value of the windfall is the probability of it occurring time the amount if it does occur. So, N becomes p*N. To make the math super easy, let's make N = $100. Let's say the probability of this windfall is 5%.

Next, we have to discount that by 10 years using the time value of money. Let's say the firms discount rate is 12 percent. (That is the opportunity cost of investing the funds in housing project X instead of the next most valuable use.)

The PV of this $100 windfall is (5% * $100) / (1.12)^10 = $1.61

You want a bigger windfall? Let's say the windfall is $1,000,000. The PV of that would be $16,098.66.

So, you can see how the low probability of the windfall and the time value of money both massively decrease the NPV of the windfall. Even a million dollar windfall ends up only worth 16,000.

Of course, the actual impact on investment is going to be less than this. Since no one actually knows what the probability of a windfall is, it is unlikely that they are relying on it when making investment decisions. They instead are likely going to be more conservative and not invest unless the NPV is still positive, even without the windfall.

Take those two factors into consideration (that the windfall isn't worth very much anyway and investors are going to tend not to rely on it when making investment decisions), and we can see that the impact on investment will tend to be very small.

"But, a good portion of these rent increases are opportunistic (not anticipated when initially deciding whether to move forward with the project)."

Opportunistic rent increases are factored into the value of investment in housing.

"A ceiling on rent increases is something that investors can handle easily."

Investors do not need rent control to place a ceiling on rent increases in their pro formas. They already include an estimated increase in rent.

"The value of community relationships is not always properly valued in our economic transactions..."

How else do you propose we value it, except through cost?

"Opportunistic rent increases are factored into the value of investment in housing."

To an extent. But not accurately and not very much. Since they can't accurately forecast, they aren't very good for getting financing.

Go ahead and try to get a huge loan based on speculation that you will "get lucky" and be able to charge more rent in the future than the bank estimates. You won't get very far. If you say to a bank, "I want an extra $10 million and at a lower interest rate, because I think in the future, some unknown political organization might take over the city and demolish much of the housing stock and prevent other developers" you aren't going to get very far. How much of your own money are you willing to gamble (and potentially lose) on such an outcome?

Not very much. And that is why if the anti-growth administration DOES happen, it is considered a windfall.

Now, keep in mind, that doesn't mean that all probabilistic bets are windfalls. There is a difference between a reliable probability that can properly go into a NPV calculation and some completely speculative thing. I good hypothetical test of the difference is whether you could go to a bank and try to get more funding or convince them that your project has less risk (so they should charge you a lower interest) by bringing up the scenario. If you can't explain it to your banker with a straight face, it is just a windfall.

"Investors do not need rent control to place a ceiling on rent increases in their pro formas. They already include an estimated increase in rent."

I did not say that investors need a ceiling on their returns. I am saying that they can calculate the impact of such a ceiling. And that rent control, if properly implemented, may not have a very large impact on their NPV calculations.

"How else do you propose we value it, except through cost?"

We can perform experiments. For example, we could study the mathematical abilities of kids who live in the same community over time versus those who move more often. Is the mathematical ability of kids who experience instability in their education lower? By how much? What are their college outcomes like? Income?

We can study rates of depression and suicide and divorce etc.

"Go ahead and try to get a huge loan based on speculation that you will “get lucky” and be able to charge more rent in the future than the bank estimates."

Multifamily is funded by both loans and equity. Equity cares about speculation of profits. It factors in the possibility (but not guarantee) that profits will be higher (or lower) than advertised. (Lenders also care, because it affects the borrowers' ability to repay the note.) What you are calling "windfalls" factor in to the demand for investment in housing.

"I good hypothetical test of the difference is whether you could go to a bank..."

Or an investor. And investors will routinely give money for the speculative promise of a higher return than the bank will get.

"And that rent control, if properly implemented, may not have a very large impact on their NPV calculations."

However implemented, rent control will have exactly one of two effects on pro formas. If the regime controls rents at amounts lower than the investor would otherwise expect from a market, their pro formas will come down. If the regime controls rents at amounts higher than the investor would otherwise expect from a market, their pro formas will be unaffected. (And if the regime is right, rent control will not work.)

"We can perform experiments."

To correct for confounding factors would be virtually impossible. But if you can do it, go get the experiments under way. In the meantime, I think it makes sense to allocate finite resources in a way that minimizes shortages, and rent control increases scarcity.

Rent control only increases scarcity IF the lack of rent control doesn't increase it even more.

Recall, that in the absence of rent control, property owners have more incentive to invest their time and money in NIMBYism because they can get an immediate return on their investment in the form of higher rents.

When you take political economy concerns into consideration, the aggregate effects aren't quite so clear. And recall, unless you know the elasticities, economics 101 only tells you about the direction of effects, not the magnitudes.

"Recall, that in the absence of rent control, property owners have more incentive to invest their time and money in NIMBYism..."

The form of this argument is that we need government intervention (rent control) because otherwise people will have perverse incentives to take advantage of government intervention (NIMBYism). The counter is that we should remove the government intervention in the first place.

Let's apply your logic to Volkswagen emission controls.

The government put emission requirements in place for automakers, and then uses a standard system to test for compliance. Some automakers cheat by using one set of engine controls when tested using the standard test, and another set of engine controls when not being tested.

Therefore, we should remove emission controls!

Wait, that can't be right.

The professional football league has rules to keep the competition fair and hopefully at least marginally safer for participants. Some teams cheat on their way to winning 11 consecutive division titles. Therefore, we should strip away the rules that most of the teams follow.

Darn it, that can't be right, either.

Computer vendors sell systems that connect to the Internet. Some people use the Internet to make unauthorized changes to other peoples' computer systems. Therefore we should all buy DiSCoUnT V1AgRa so we can meet single moms in our area who are DTF RIGHT NOW!

By the way, no, equity in NPV calculations does NOT rely on windfalls that can't be predicted, who probabilities are completely unknown, and whose magnitudes are unknown.

There are probabilistic events that belong in an NPV calculation. But they are not extravagant events where you can't articulate the probability, the magnitude, or even the direction of impact (whether positive of negative) on your bottom-line.

To the extent that rent increases are based on windfalls that were not considered and could not rationally be considered in making the decision to invest, then rent control simply does not change the calculus.

You might say that equity holders want those windfalls. Of course they do! But if they didn't go into the decision to invest, they don't matter (very much). For the most part, an investor is going to rely on a plan for earning money, not guessing or speculation.

Note that my argument is one about magnitude, not direction. Obviously, taking some of the "lottery ticket" value out of the investment is going to decrease the NPV of the project. But unless that "lottery ticket" is somehow anticipated by the investor in some systematic way, not as much as a more regular expectation. Obviously, there is some value in capturing "random completely unplanned events with are good for me." But you have to discount the value not only with a PV calculation, but also the high uncertainty. Or to put it another way. If the investor does not calculate it or even think about it much as a possibility, it is going to have a low impact on their decision-making.

Spot on. Philly tried this once. What did people do when the tax breaks expired? They just moved. Unsurprisingly, wealthy people are able to move more quickly in response to oppressive tax regimes.

"If you do that you are going to drive up the initial rents, making housing more expensive. "

Initial rents can't go any higher than the market will bear, which is coincidentally the price level that a competitive market prices them at.

If you are operating in an environment that restricts rent increases you will charge higher initial rents than otherwise.

If you can't collect those, then you will look elsewhere to invest your money.

If you are a business that makes money buy owning and renting apartments, you will make money by owning and renting apartments. If you are a business that makes apartments, you will continue to make apartments. Ideal economics says you'll turn and change on dime to pursue other opportunities... but in the non-ideal REAL world, businesses simply aren't that agile.

"I agree with Somin on the zoning issue."

So you take the un-libertarian position that government policies should be made far away from the impacted serfs? That is, state zoning, not local zoning?

First, you do need SOME zoning. Industrial uses of land need to be separated from residential uses. But separation between commercial and residential is not necessary and, is in fact, highly inefficient.

Yes, making the decisions at the state level if better. Not because locals are "serfs" but because some locals take advantage of other locals (or those who would like to become locals).

Who has time to go to local planning meetings? Only busybodies without much else to do, really. Or, alternatively, those with a concentrated economic stake in the outcome of a decision. We say that the combination of these busybodies and economic actors "represent" the local community, but they don't really. That is a complete fiction.

Given the fictional nature of the representation at the local level, it makes sense to make the decision at the state level.

I don't want any commercial properties near where I live; I want neither the traffic nor the kinds of people that brings in.

So instead of having regulations at the local level, where I can actually have an influence, you want to move them to the state level, where only lobbyists, technocrats, cronies, and unions can influence them? That's absurd.

Just because your community is dysfunctional doesn't mean every community is. Nor does it mean that I would like to see my community destroyed because your community can't get its act together.

The "kinds of people" it brings?

You mean human beings, right? I can tell already, we wouldn't get along. Traffic? Separating housing from commercial CAUSES traffic, because people have to drive whenever they need something. You CLEARLY haven't thought this through.

"So instead of having regulations at the local level, where I can actually have an influence"

Just because you don't have a job or are extremely motivated, you can have influence on local politics. The rest of us actually have things to do and don't want to be influenced by you. You don't represent us.

"Just because your community is dysfunctional doesn’t mean every community is."

It is not about a community being functional or dysfunctional or some crazy binary like that. It is about it local government reflecting the preference of the people who actually live there and theoretically but not actually represented. When people can't monitor local government (which is always, because who has the time), local government will tend to diverge from their preference.

I am fine with local autonomy. We can have local elections on big issues that matter to us to make local rules where everyone has a vote. New England town style. But no permanent "representatives" who fail to represent. That we can do without.

I’ve lived in lots of places around the world. I don’t want 99% of the human beings on this planet living in my neighborhood. I like to live in upscale US neighborhoods where everybody is in the top 20% of the income distribution.

Oh, my, I’m heartbroken! A progressive who doesn’t like me!

Most people in the US already have to drive whenever they need something (or have it delivered). My neighborhood is like that. We like it that way. We like neighborhoods in which everybody has a car, in which we recognize every neighbor and every car by sight. Where most driveways have a couple of cars and an RV. Where we know where the police chief lives. We don’t want stores in our neighborhoods, or high density housing, or rental housing, or public transportation. We drive to those; they are near the cheap apartment housing near the highway. You know, where most of the people who live in my neighborhood now used to live when we were younger and hadn’t yet made as much money.

Works fine around here. If it doesn’t work in your community, that’s your problem, not anybody else’s.

I think the libertarian position is no zoning. That's why you see Somin praising local no zoning regimes (Houston) and statewide efforts to curb local zoning.

The problem with that is externalities.

People experiencing higher rates of cancer, heart disease, stress, etc. because they live too close to an industrial area is not a good thing.

Maybe some libertarians don't care about that. *shrug*

Anarchists might not but I assume libertarians do. I think the libertarian position is that there are certain forms of regulations that don't work whether at the local or statewide level, at all, full stop. But that to the extent regulation is necessary (to deal with some externality, for instance), the bias is towards local rule because democracy laboratories, or something. There are some externalities that can only be dealt with at the largest level. (Montana does not have the resources to repel an invasion by a world power.)

And then there are the thousands of regulations that might be permissible according to a libertarian but not mandated. Maybe libertarian Tom and libertarian Andy agree that public education is important, but to different extents, and so may agree that each jurisdiction should have the liberty to decide on the extent of public spending on education.

I think a libertarian who thought about it ought to prefer regulation at the state level, not the federal level or the local level.

At the state level, you get your laboratories of democracy. But you also have enough interest to ensure accountability. It is beyond the capacity of most people to monitor so many elected officials, much less hold them accountable for their performance. For this reason, I think ideally state government would follow the presidential model, with the only elected executive official being the governor.

When you think of local government, maybe you should think about "speed traps," "asset forfeiture for profit," etc. This is because local communities have so much difficulty monitoring and controlling local officials. Ordinary people (those with jobs) tend not to have time to keep track of it all. But they can keep track of state politics and federal politics a little better. Also, as the scope of a politicians responsibilities expand, their tendency and interest in engaging in petty tyrannies also decreases.

There are cases of local government being effective. But I think the dispersal of accountability is too high of a price to justify it. Especially in our modern society, which is highly mobile.

"I think a libertarian who thought about it ought to prefer regulation at the state level, not the federal level or the local level."

Like everyone else, they tend to approve of regulation that lies along the path of what they already intended/wanted to do, and object to regulation that keeps them from doing what they wanted/intended to do.

"I think a libertarian who thought about it ought to prefer regulation at the state level, not the federal level or the local level."

Sure, but the choices aren't between "regulation at the state level" and "regulation at the federal level". It could be between "regulation" and "no regulation". The 14A is a federal regulation of state behavior. Do you suppose libertarians are against the 14A? I suspect they support it, at least when interpreted to prevent states from interfering with individual liberties.

"Do you suppose libertarians are against the 14A?"

There are (at least) as many kinds of libertarianism as there are libertarians. So, yeah, I bet you could find some libertarians who are against the 14A.

"No zoning" doesn't mean "anything goes", it just means that people will have to form private HOAs with CC&Rs and voting only by property owners.

In fact, incorporated towns roughly started out like that, but they became less and less free market as there were more state and federal regulations piled on them.

Either way, there is a market demand for certain kinds of neighborhoods, and the market will supply a way of imposing the necessary restrictions on neighborhoods, one way or another. If you don't like those restrictions, move somewhere else.

HOAs are awful. If you enjoy the petty tyranny of busybodies, this is for you.

Concur. If your analysis leads you to suggest that HOAs produce the results you want, there's something wrong with your analysis.

HOAs are whatever the owners choose to make them. Some HOAs only exist to divide up the cost of road maintenance. Others simply impose legal restrictions similar to zoning. In condo buildings and townhouse developments, HOAs are a necessary evil for dealing with noise and other nuisances, as well as to pay for maintenance of common areas.

Many people currently don’t need HOAs because zoning fulfills all their needs. If zoning can’t be implemented due to state law, people will create HOAs that substitute. The CC&Rs may simply say: “restrictions: only single family homes between 2500 and 5000 sq ft, with a maximum of one home per acre of land”.

The main problems with land use is one of different time ranges. If the best use of land short-term doesn't match up with the best use of land longer-term, you wind up with waste because what is built in the short term has to be demolished to make room for the best use longer-term.

The libertarian position is that zoning should be replaced by private CC&Rs according to market demand and not subject to the vagaries of politics.

That’s not the same as taking a state with local zoning rules and simply abolishing them by fiat at the state level because that leaves neighborhoods without either zoning or CC&Rs.

An otherwise interesting and informative article here is ruined by the needless use of "left" and "liberal". Totally unnecessary to telling the story, and shows the imagination of a pre-school child. Same with "right" and "conservative". Terms meant solely to divide.

They're meant to classify, which is a good thing. Correct labels don't divide; they merely reflect existing divisions.

Also, they were necessary to this story; the point was that people who support certain policies are acting contrary to their values.

" the point was that people who support certain policies are acting contrary to their values."

This argument is flawed, in the sense the the people being identified as acting contrary to their values haven't been asked about their values, or their actions. When people write about what they guess other people are thinking, the results are often comical and seldom useful.

Well, I'll defer to your demonstrated expertise at making comments that are seldom useful.

At least I can manage "seldom"... keep trying though, you'll EVENTUALLY learn how.

I know _how_ to be that unhelpful; I just choose to surpass that low bar.

So you're proud of how much more unhelpful you can be? Cool.

Yeah, rent control is stupid and doesn't work. Good point.

But to agree with the abolishment of single family zoning is the most ignorant think that I have ever read on Reason. Since it will take decades to turn neighborhoods into Haiti slums, I may not see it but it is certain to be the result. It is the most ineffective way to densify and this can be proven in many ways. But turning a single family house into two units is much less efficient than building a new, high density condo complex in a downtown area or where Sears used to be.

What is most hilarious, and actually very common by self proclaimed free market types, is the claim of "over regulation" when a government establishes rent control but cheering when a State government bans local governments (which are the purest form of government, closest to real people) from maintaining single family zoning. So to the author, playing your own game: why do you support authoritarian rule?

and another thing: exclusionary zoning is one of the most overrated issues out there in the zoning politics world. There are very few places in the US where all housing land uses are "excluded." There may be some places, but they are very rare and when they happen they are caused by local governments that are influenced by, oh I don't know...the free market of voter opinion.

The bottom line is that there isn't a housing problem in the US at all. The problem is that jobs are in the wrong places. The writer of this article is begging for government overreach by the State dictating local zoning rules, so why don't we just use the government overreach to provide incentives for companies with jobs to radiate to areas where housing is plentiful and more affordable.

The "free market of voter opinion" is word soup. Voting and markets are orthogonal concepts.

Of course the exclusionary zoning is caused by voters. It's called NIMBYism; everyone's familiar with it. That's not a defense of it.

Not at all. Corporations and HOAs are private, free market associations of people, and they are governed by voting.

The "defense of it" is that if I want to get together with 200 neighbors and form an association that ensures that our neighborhood stays the way we want it to, that's our right in a free market. Traditionally, the legal form to do this was an "incorporated town". Given all the crappy state and federal regulations of towns, that legal form has been precluded so that we have to move to fully private HOAs if we want that level of control over our neighborhoods.

our neighborhood stays the way we want it to

Um, wow. Are you a white person from the 1960s or what?

Nah, the black folks experiencing gentrification also pine for their neighborhood the way it used to be, and want to keep it that way. In cities large enough, you had multiple ethnic enclaves that the residents yearn to keep.

This isn't just a "white folks" thing, nor only of the past.

No, as a matter of fact, I’m an immigrant. Immigrants often like to live in communities of people with similar backgrounds. Imagine that.

"Not at all. Corporations and HOAs are private, free market associations of people, and they are governed by voting."

We are talking about zoning regulations imposed by the government on property owners, not voluntary associations imposed on the property owners by themselves.

Why are we differentiating? Either you can do it, or you can't, and it doesn't make much difference why you can't if you can't.

David claimed that “voting” and “markets” are “orthogonal concepts”. I pointed out that markets commonly produce governance structures that function through voting; in fact, towns and HOAs function very much the same, and corporate governance happens through voting among the owners.

As to your comment, being subject to the rules of a town or HOA is a voluntary choice; you make that choice when you buy property in a particular location. In both cases, there is a risk that the governance of the town/HOA won’t function according to your preferences, a risk you need to evaluate before you buy.

"There are very few places in the US where all housing land uses are 'excluded.'"

Consider the urban growth boundary of Portland, OR. The basic idea is to keep productive farmland as farmland, rather than into sprawling suburbs.

"...There are very few places in the US where all housing land uses are “excluded.”..."

Irrelevant.