The Volokh Conspiracy

Mostly law professors | Sometimes contrarian | Often libertarian | Always independent

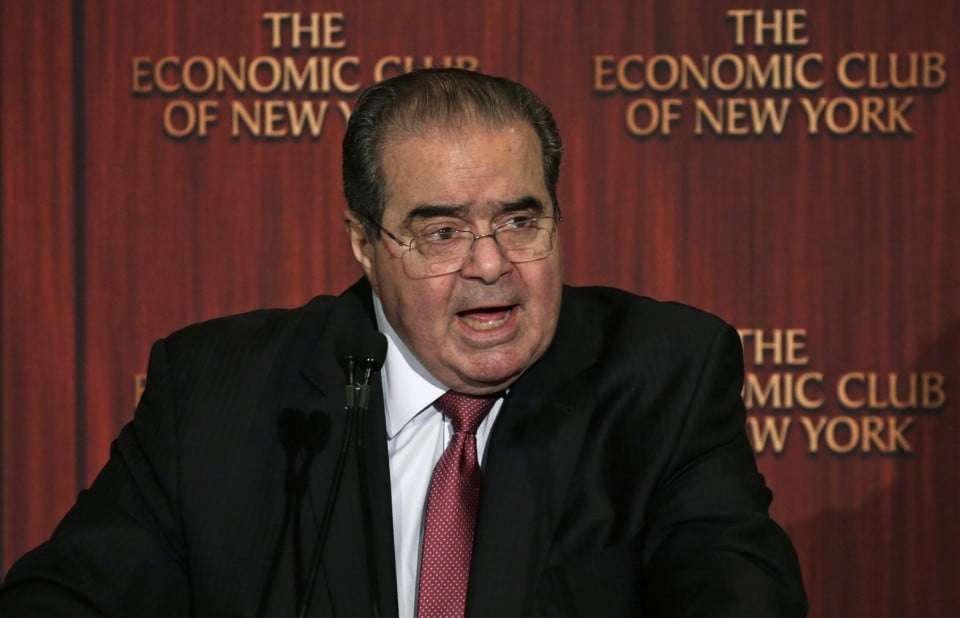

How Scalia-esque will Donald Trump's Supreme Court nominee be?

On Wednesday morning, President Trump tweeted that he will announce his pick to replace the late justice Antonin Scalia on the Supreme Court next Thursday, Feb. 2. According to various news reports, Trump has met with at least three potential nominees and that these three are the leading candidates for the nomination: Judge Neil Gorsuch of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 10th Circuit, Judge Thomas Michael Hardiman of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 3rd Circuit and Judge William Pryor of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 11th Circuit, with Gorsuch holding an edge (at least at the moment).

During the campaign, Trump said he would "appoint judges very much in the mold of Justice Scalia." But what does this mean? All three of the reported finalists are highly qualified, conservative justices. All would make for strong Supreme Court justices, as would others often mentioned as top-tier candidates to replace Scalia, such as Judge Diane Sykes of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 7th Circuit and Judge Raymond Kethledge of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 6th Circuit. Is a judge "in the mold of Scalia" simply a judge who generally shares Scalia's judicial philosophy? Or is it also a judge who shares some of Scalia's other characteristics, such as his specific judicial philosophy or his wit?

A group of researchers recently sought to quantify what it is that makes a judge like Scalia and used its measure to evaluate the records of those identified by then-candidate Trump as potential Scalia replacements. To generate a "Scalia Index Score," the researchers considered the following:

- How often does a judge promote or practice originalism?

- How often does a judge cite Scalia's non-judicial writings, writings that were not about the substance of the law but about how to think about interpreting the law?

- How often does a judge write separately, something Scalia did 25.9 percent of the time when he was not writing the majority opinion over his last 20 years on the court?

The researchers have updated their evaluation in light of recent reports as to which candidates are at the top of Trump's list, and here is what they found:

We have updated the paper in light of recent developments (see pages 12-15). Specifically, the shortlist is now rumored to be down to three names: Gorsuch, Hardiman, and Pryor. We have calculated the likelihood that the potential nominees will be the most Scalia-like of the group, and for comparison's sake have added data on Chief Justice John Roberts and Justice Samuel Alito from their time on the D.C. Circuit and Third Circuit, respectively. We find that Gorsuch (62.2-79.4%) and Pryor (70.5-76.7%) have much higher likelihoods of being the most Scalia-like of the potential nominees than Hardiman (34.8-42.9%). In fact, Hardiman looks more like John Roberts (32.6-33.7%) or Samuel Alito (39.4-52.8%) did when they were federal appellate judges.

The full paper, "Searching for Justice Scalia: Measuring the 'Scalia-ness' of the Next Potential Member of the U.S. Supreme Court" by Jeremy Kidd, Riddhi Sohan Dasgupta, Ryan D. Walters, and James Cleith Phillips, is available on SSRN.

http://www.washingtonpost.com/video/national/trump-says-will-announce-supreme-court-pick-next-week/2017/01/24/c76a86c0-e257-11e6-a419-eefe8eff0835_video.html

The Scalia-ness study is interesting, but it is also limited. Does a judge cite Scalia's non-judicial writings because they have a particular affinity for Scalia's way of thinking? Or because they are more prone to citing non-judicial writings generally? Do they write more often separately because they are particularly independent and principled? Or because of their relationships with their colleagues or willingness to write about extraneous issues in cases?

In addition, as I've discussed before, a judge's record on an intermediate court is not always predictive of how that judge would perform on the Supreme Court. Lower court judges have an obligation to follow circuit and Supreme Court precedent and may feel constrained when it comes to addressing broader or more foundational questions in specific cases. Judges on lower courts are also less likely to be asked by litigants to reconsider precedents or pave new ground, so they have less occasion to even ask some of the larger questions.

While I am reluctant to place too much weight on the Scalia-ness study, it nonetheless provides an interesting way to think about the relative strengths of various candidates and highlights some aspects of judging that often get lost in discussions of judicial nominations. Partisans quickly focus on how they think a given judge might vote in a given case and tend to ignore why the judge might vote that way.

On the subject of thinking about how potential Supreme Court nominees think, two of the three leading candidates mentioned above - Gorsuch and Pryor - recently delivered the Sumner Canary lecture at the Case Western Reserve University School of Law, and each published an article based upon their lecture in the Case Western Reserve Law Review. These lectures provide valuable insights about the law and the thoughts of these two jurists. Here are links to the video and printed version of each lecture.

- Neil Gorsuch, "Of Lions and Bears, Judges and Legislators, and the Legacy of

Justice Scalia" (video) (published version) - William Pryor "The Separation of Powers and the Federal and State Executive Duty to Review the Law " (video) (published version)

Show Comments (0)