Repudiating the 'Dual Sovereignty' Exception to the Double Jeopardy Clause Could Undermine the Federal War on Weed. Oh No!

The Supreme Court seems disinclined to overturn precedents allowing serial prosecutions of the same crime.

Judging from yesterday's oral arguments in Gamble v. United States, most members of the Supreme Court do not seem inclined to reconsider the "separate sovereigns" exception to the constitutional ban on double jeopardy. That doctrine, also known as "dual sovereignty," allows serial state and federal prosecutions for the same crime on the grounds that breaking the laws of two governments constitutes two offenses. While that rule seems inconsistent with the original public understanding of the Due Process Clause, most of the discussion yesterday focused not on the merits of that argument but on the dangers of overturning a longstanding yet historically dubious holding.

There is some dispute about exactly how old the dual sovereignty doctrine is, because the Supreme Court alluded to the idea as early as 1847 and enunciated it more explicitly in 1852 but did not officially embrace it until 1922, when it approved a federal prosecution for bootlegging after a state prosecution. In 1959 the Court approved a state prosecution for robbery following a federal acquittal for the same crime. Justice Elena Kagan described the dual sovereignty doctrine as "a 170-year-old rule," which is how Assistant Solicitor General Eric Feigen framed it. Louis Chaiten, the lawyer representing Terance Gamble, who is challenging his federal conviction for illegal gun possession following his state conviction for the same crime, disagreed with that characterization. But however you date the doctrine, several justices were clearly uncomfortable about overturning what they view as a venerable principle of constitutional law, even assuming that principle is fundamentally mistaken.

In addition to the repeated invocations of stare decisis, there was much discussion of the practical consequences of repudiating the separate-sovereigns exception. On that point, some of Feigen's hypothetical horrors look more like benefits to me. Without the dual sovereignty doctrine, he warned, the federal government might not be able to launch duplicative prosecutions of mass murderers, such as the perpetrator of the Pittsburgh synagogue massacre, who are already being prosecuted in state court. Since such federal cases are completely gratuitous and impinge on state autonomy, that strikes me as an argument in Gamble's favor.

And don't get Feigen started on marijuana. "Let's say someone's caught in California with 100 kilograms of marijuana, which is a misdemeanor in California, as the states point out in their brief, but is a felony under federal law," he said. "And he agrees to plead to the state offense, and, therefore, that would bar a federal prosecution for possession with intent to distribute" (which would trigger a five-year mandatory minimum). If you believe the Commerce Clause does not give Congress the authority to prohibit intrastate possession of marijuana and/or that people should not go to prison for conduct that violates no one's rights, Feigen's nightmare of state interference with the federal war on weed looks more like a dream come true.

Chaiten was keen to reassure the justices that the impact of enforcing the Double Jeopardy Clause as it was intended would be modest. Federal civil rights cases could still proceed even when based on conduct already punished by a state, he said, because the federal offenses involve additional elements, making them distinct crimes. Federal courts need not count foreign prosecutions of terrorists who kill Americans toward double jeopardy, he said, unless they recognize "the competent and concurrent jurisdiction of the first court." He also noted that 20 states have statutes that generally bar a second prosecution for a crime that has already been prosecuted by a "separate sovereign," while another 17 apply that rule to certain crimes, and that "seems to have worked out OK."

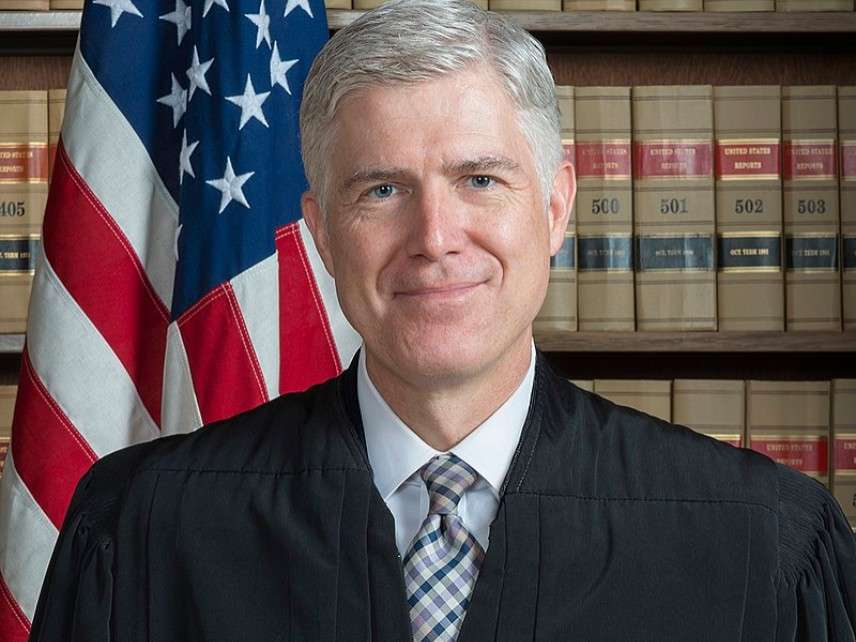

The justices who seemed most sympathetic to Chaiten's position were Ruth Bader Ginsburg and Neil Gorsuch.

"Is there another case where federalism has been invoked to strengthen the hand of government, state and/or federal, vis-á-vis an individual?" Ginsburg asked Feigen. "Federalism is usually invoked because it's a protection of the liberty of the individual, but here the party being strengthened is not the individual; it is the state's freedom and the federal government's freedom to prosecute the same offense."

Ginsburg was echoing a point that Gamble's lawyers made in their brief, and Gorsuch expanded on it. "I had thought in this country that the people were the sovereign and that…exercise of sovereignty was divided, not multiplied," he said. "So it was divided between the federal government and the state governments, Ninth and 10th Amendment. And that it is awkward, isn't it, to say that there are two sovereigns who get to multiply offenses against you? I can't think of another case where federalism is used, as Justice Ginsburg indicated, to allow greater intrusions against the person, rather than to protect more against them."

Gorsuch raised another argument emphasized by Gamble's lawyers: "With the proliferation of federal crimes, I think over 4,000 statutes now and several hundred thousand regulations [violations of which can be charged as crimes], the opportunity for the government to seek a successive prosecution if it's unhappy with even the most routine state prosecution is a problem."

Gorsuch also noted that the dual sovereignty rulings preceded the Court's application of the Double Jeopardy Clause to the states via the 14th Amendment. "We were concerned that the federal government would be at a disadvantage compared to states without this rule because states were not bound then by the Double Jeopardy Clause and could pursue a second prosecution after a failed federal prosecution," he said. "That rationale has now disappeared with incorporation."

Clarence Thomas, as is his wont, was silent during the oral arguments. But Chaiten's originalist claim seems like one that would appeal to Thomas, who two years ago joined Ginsburg in urging the Court to revisit the dual sovereignty doctrine. "The double jeopardy proscription is intended to shield individuals from the harassment of multiple prosecutions for the same misconduct," Ginsburg wrote in a concurring opinion joined by Thomas. "Current separate sovereigns doctrine hardly serves that objective." She added that "the matter warrants attention in a future case in which a defendant faces successive prosecutions by parts of the whole USA."

The fact that the Court is hearing this case means at least two justices agreed with that recommendation. It looks like Gorsuch was one of them, and I'd guess that Chief Justice John Roberts was the other. Yesterday Roberts said he thought Chaiten was right that "we have not had a full consideration and exposition of the issue in any of our precedents." He also noted that the Justice Department's guidelines for serial prosecutions, which the government says can prevent any potential unfairness, show there is cause for concern. "That's an odd defense of a position to say, well, we take care of it somewhere else, so don't worry about it," he told Feigen.

Still, I see four votes at most in favor of reconsidering the dual sovereignty doctrine, which the Gamble brief calls "as uniformly criticized a rule of constitutional law as any," saying, "Even within legal academia—which tends to reward unconventional viewpoints—defenders of the exception are nowhere to be found." Given the Court's inclination to respect old precedents simply because they are old, even an indefensible principle is hard to dislodge.

Show Comments (56)