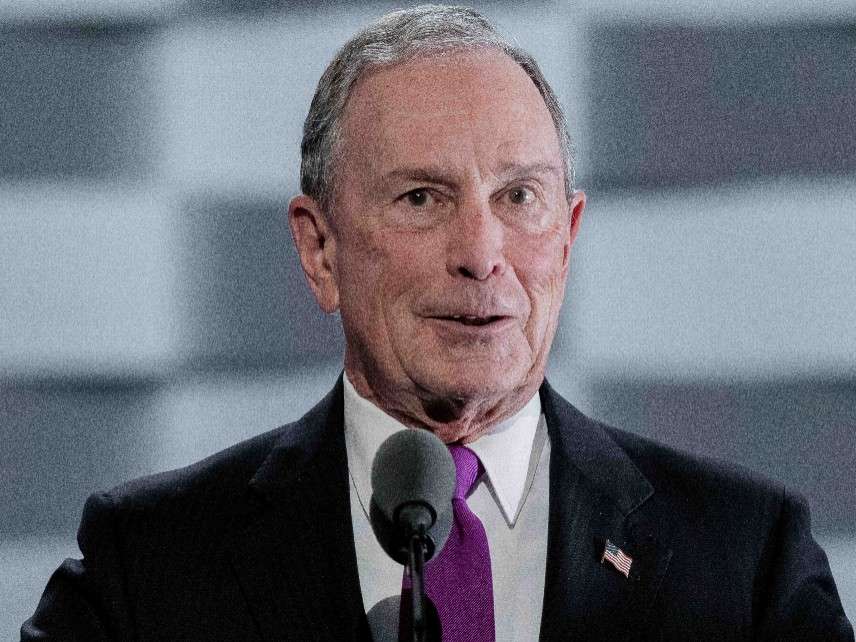

Michael Bloomberg Thinks Charlie Rose, Unlike Random Black Dudes, Deserves a 'Presumption of Innocence'

The former New York mayor defends his stop-and-frisk policy while suggesting the famous TV host did not get a fair hearing.

Michael Bloomberg, the billionaire media mogul and three-term mayor of New York City, thinks Charlie Rose, the veteran TV journalist who last year lost his gigs at CBS and PBS after eight women accused him of sexual harassment, deserves the "presumption of innocence." But Bloomberg, who is mulling a run for the Democratic presidential nomination in 2020, applies a different standard to young, dark-complexioned men, whom he thinks should be stopped and frisked at random in the name of public safety.

The contrast between those positions, which Bloomberg took in a recent interview with The New York Times, illustrates the natural tendency of wealthy, powerful men to sympathize with people in their own social circle while overlooking the interests of people who do not look like them or live in their neighborhoods. That tendency is especially dangerous when it shapes government policy, as it did when Bloomberg was the mayor of New York.

Bloomberg, a fan of Rose's whose company hosted his studio and distributed his long-running interview show, is not sure what to make of the charges against him, which included allegations of groping, lewd phone calls, and unwelcome exhibitionism. "The stuff I read about is disgraceful," Bloomberg told the Times, but "I don't know how true all of it is….We never had a complaint, whatsoever, and when I read some of the stuff, I was surprised, I will say. But I never saw anything, and we have no record. We've checked very carefully." Asked if he believes Rose's accusers, Bloomberg said, "Let the court system decide."

That stance regarding claims that may never be addressed by a judge or jury, coupled with Bloomberg's reference to the presumption of innocence, suggests he is applying an inappropriate legal standard to private business decisions. While it would be neither fair nor smart for a company to automatically accept accusations of wrongdoing against a valued employee, neither CBS nor PBS had an obligation to demand proof beyond a reasonable doubt. Furthermore, Rose, while hedging on some of the details, admitted he was guilty of "inappropriate behavior" that had caused the women "pain"—a point that Bloomberg conspicuously ignores.

"It is essential that these women know I hear them and that I deeply apologize for my inappropriate behavior," Rose said. "I am greatly embarrassed. I have behaved insensitively at times, and I accept responsibility for that, though I do not believe that all of these allegations are accurate. I always felt that I was pursuing shared feelings, even though I now realize I was mistaken. I have learned a great deal as a result of these events, and I hope others will too. All of us, including me, are coming to a newer and deeper recognition of the pain caused by conduct in the past, and have come to a profound new respect for women and their lives."

In contrast with Rose, the young men who were stopped, questioned, and patted down by police officers during Bloomberg's administration, who were overwhelmingly black or Latino, typically had done nothing wrong. Such stops, which surged to record levels under Bloomberg, peaking at 686,000 in 2011, almost never discovered guns and resulted in citations or arrests in just one case out of 10. That track record is important in understanding why a federal judge concluded that the program was unconstitutional, since the Supreme Court has said the Fourth Amendment allows police to detain someone only when they reasonably suspect he is involved in criminal activity and to pat him down only when they reasonably suspect he is carrying a weapon.

When he was mayor, Bloomberg did not even bother to pretend the NYPD was complying with those standards. He defended the stop-and-frisk program not as a way of catching criminals or taking guns off the street but as a way of discouraging people from carrying weapons. To his mind, the fact that cops rarely found guns when they patted people down meant the program was working. But the Supreme Court has said suspicionless dragnets aimed at detecting or deterring crime are inconsistent with the Fourth Amendment. In other words, Bloomberg unwittingly admitted the stop-and-frisk program was unconstitutional while defending its effectiveness.

To this day, Bloomberg does not seem to understand that point. According to the Times, "He said stop-and-frisk searches had helped lower New York's murder rate and insisted that the policy had not violated anyone's civil rights." He suggested that many Democrats would seen things his way. "I think people, the voters, want low crime," he said. "They don't want kids to kill each other."

Bloomberg's argument that the stop-and-frisk program was effective is questionable. His argument that it was constitutional is nonexistent. While Bloomberg invents legal standards to benefit his friend Charlie Rose, he completely ignores the constitutional safeguards that are supposed to protect people he has never met from police harassment.

Show Comments (22)