DOJ Promises 'Aggressive' Response to Lifesaving Supervised Injection Facilities

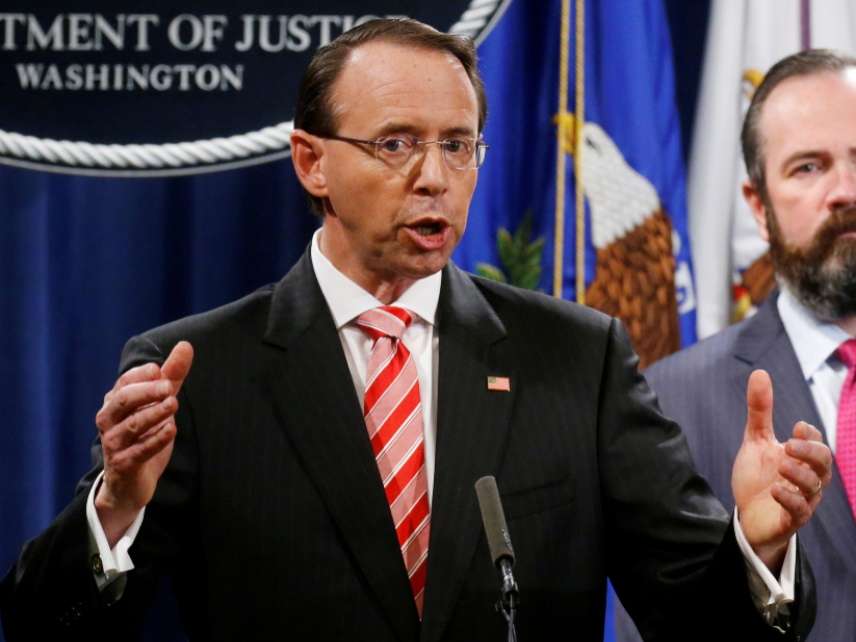

Deputy Attorney General Rod Rosenstein condemns "havens" for drug users, notwithstanding their proven benefits.

For anyone who was wondering how the Trump administration might respond to plans for supervised injection facilities (SIFs), which aim to reduce drug-related disease and death by offering a safe, sanitary, and medically monitored environment where people can inject illegal substances, Deputy Attorney General Rod Rosenstein makes it clear in a recent New York Times op-ed piece that the Justice Department is firmly opposed to the idea. What's not clear is why.

Rosenstein complains that local governments plan to "subsidize" SIFs, which he describes as "taxpayer-sponsored haven[s]" for drug users. Given the billions of dollars that the government routinely squanders on anti-drug efforts that are not just ineffective but counterproductive, a strong argument can be made that harm reduction programs like SIFs are a far more efficient use of taxpayer money. But they need not involve any public expenditure. The SIFs under consideration in New York City, for instance, would be funded and run by nonprofit organizations. With that sort of arrangement, government's role is limited to getting out of the way.

Rosenstein says SIFs "are very dangerous and would only make the opioid crisis worse." Yet research has found that SIFs, which operate legally in 66 cities and 11 countries but are prohibited in the United States, help prevent fatal overdoses, control the spread of HIV and hepatitis C, reduce skin and soft tissue infections, and encourage enrollment in drug treatment.

A 2010 study estimated that Insite, a Vancouver SIF that opened in 2003, saves five times as much money as it costs. According to a 2016 cost-benefit analysis, a SIF in San Francisco would save $2.33 for every dollar spent on it. A 2017 summary by the Penn Wharton Public Policy Initiative concluded that "the effectiveness of SIFs is clear," which helps explain why the American Medical Association supports their legalization.

Instead of evidence, Rosenstein offers bluster and non sequiturs. "Proponents of injection sites say they make drug use safer," he writes, "but they actually create serious public safety risks." Such as?

"Many people addicted to opioids use illicit fentanyl or one of its analogues, which can be up to 5,000 times more powerful than heroin," Rosenstein notes. "Users often have no idea what they are actually buying from criminal drug dealers." And whose fault is that? Rosenstein, who supports a prohibition policy that results in life-threatening uncertainty about drug potency, is complaining about programs that aim to reduce the casualties from that government-created hazard.

Rosentein claims "injection sites destroy the surrounding community," citing the account of a Redmond, Washington, city council member who visited Vancouver. Yet as the Penn Wharton summary notes, "Studies have found that the opening of Insite in Vancouver led to no visible effect on drug trafficking, assaults, or robbery." In fact, "breaking and entering of vehicles and vehicle theft diminished in its surrounding neighborhood." Research in Australia "found similar results." Studies of Insite indicate that SIFs reduce public injection and drug-related litter such as used syringes.

Ultimately Rosenstein falls back on the argument that SIFs should not be tolerated because they are illegal, which is not exactly a rousing defense of current policy. "It is a federal felony to maintain any location for the purpose of facilitating illicit drug use," he notes. "Violations are punishable by up to 20 years in prison, hefty fines and forfeiture of the property used in the criminal activity. The law also authorizes the federal government to obtain civil injunctions against violators. Because federal law clearly prohibits injection sites, cities and counties should expect the Department of Justice to meet the opening of any injection site with swift and aggressive action."

The federal drug paraphernalia statute makes an exception for locally approved needle exchange programs, and Congress could add a similar accommodation for SIFs to the so-called crackhouse statute cited by Rosenstein. But even without such a change, Rosenstein's aggressive posture is not required by law, since the Justice Department has a great deal of discretion in deciding how to allocate its resources. Shutting down SIFs, which do not distribute drugs but merely provide a safer place to use them, should not be a high priority for any U.S. attorney who wants to reduce drug-related harm.

Show Comments (40)