The Handful of Counties Still Imposing the Death Penalty Are a Constitutional Mess

The death penalty is disappearing, but where it still exists, it's plagued by constitutional problems, a new report finds.

Jefferson County has produced more death row inmates than any other county Alabama, and it's no accident. In one case, a Jefferson County prosecutor claimed a man with an IQ of 56 was faking mental retardation. In another, prosecutors secured a death penalty sentence by presenting illegal evidence to the jury.

Jefferson County is one of a dwindling number of counties in the U.S. where prosecutors still doggedly pursue the death penalty, and where it is plagued by inadequate defense, prosecutorial misconduct, and racial bias, according to a report released Wednesday by the Harvard Law School's Fair Punishment Project.

While the death penalty is still on the books in 30 states—although it is inactive in four of those due to governor-imposed moratoriums—only a dwindling handful of "outlier counties" are responsible for the vast majority of new death penalty sentences being imposed. The Fair Punishment Project released a report earlier this year finding that, out of the roughly 3,000 counties in the U.S., only 16 have imposed more than five death penalty sentences since 2010. The majority of those counties are in Southern states like Florida, Louisiana, and Alabama, but they also include Dallas County, Tx. and populous Southern California counties like Los Angeles County, Orange County, San Bernardino, and Riverside.

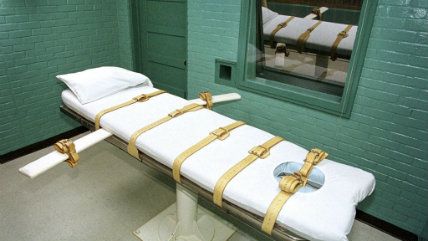

But in the few places where the "machinery of death," as Supreme Court Justice Harry Blackmun once famously called it, is still up and running, it is seriously flawed. Wednesday's report, part two of The Fair Punishment Project's study on these outlier counties, identifies what it says are systemic constitutional deficiencies with how the death penalty is applied.

"These outlier death penalty counties are defined by a pattern of bad defense lawyering, prosecutorial misconduct and overzealousness, and a legacy of racial bias that calls into question the constitutionality of the death penalty," Rob Smith, one of the report's researchers, said in a statement.

Reviewing nearly 400 direct appeals opinions handed down between 2006 and 2015 in the 16 counties, the Fair Punishment Project found forty percent of cases involved a defendant who had some form of intellectual disability or severe mental illness.

The report also found that defense attorneys in death penalty cases in the 16 counties often don't have the time, resources, or ability to adequately defend their client.

However, sloppy, overzealous prosecutors sometimes manage to defeat themselves, despite the best (or worst) efforts of inadequate defense counsels. Ten of the 16 counties reviewed had at least one person released from death row since 1976, the report found.

In Dallas County, Tx., for instance, at least 51 people have been exonerated of serious crimes since 1989, including James Lee Woodard, who served 28 years in prison for murder and rape after prosecutors hid key evidence from his defense counsel. He was exonerated by DNA testing in 2008.

The report also found systemic racial bias was a factor in most of the counties reviewed. Out of all of the death sentences obtained in the counties between 2010 and 2015, 46 percent were given to African-American defendants and 73 percent went to people of color.

A more striking disparity, though, is the imposition of the death sentence based on the race of the victim. No white defendant received the death penalty for murder of a black victim in 14 of the 16 counties, while at least one black defendant was sentenced to death for the murder of a white victim in 14 of the 16 counties

"In looking at these outlier counties, it is very clear that race is still playing a role in determining who is sentenced to die," UNC Chapel Hill professor Frank Baumgartner, whose research on racial bias in the death penalty has reached similar conclusions, said in a statement.

The Fair Punishment Project concludes that the totality of evidence presented "offers further proof that, whatever the death penalty has been in the past, today it is both cruel and unusual, and therefore unconstitutional under the Eighth Amendment."

Show Comments (41)