CBO's Latest Budget Report Is a Reminder That Debt and Deficits Haven't Gone Away

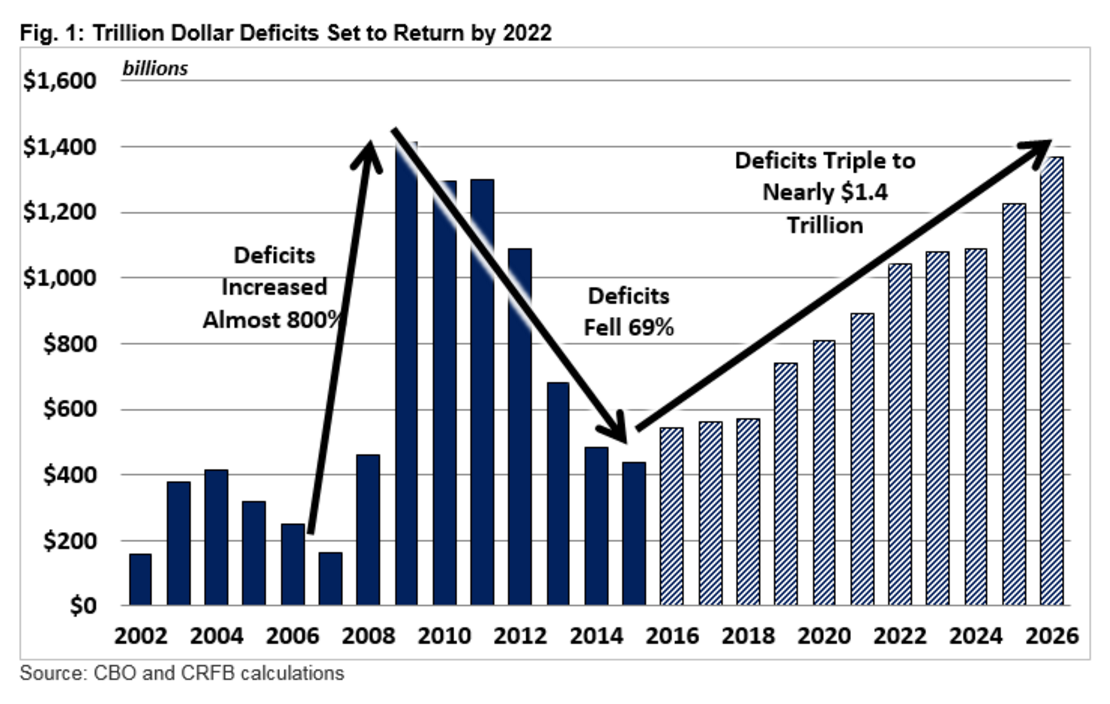

Trillion dollar deficits are on their way back.

You haven't heard the words debt or deficit very often on the campaign trail recently, and there's a reason for that: After the trillion-dollar deficits of President Obama's first term, the nation's annual fiscal has fallen down to less immediately worrying levels. Last year's deficit was just $439 billion—still historically high in unadjusted dollar terms—but also equivalent to about 2.5 percent of GDP (gross domestic product), which many economists think is basically manageable. At least, that is, if you can reliably hold it at that level.

And that's where the problem begins: As a report released this afternoon by the Congressional Budget Office confirms, the annual deficit is creeping back up this year—to $544 billion. That's worrying not only because it's higher than last year, but because, for the first time since 2009 it's rising as a share of the economy, to about 2.9 percent of GDP. Not only that, but the deficit is set to rise every year for the next decade, pushing us back over the trillion-dollar mark by 2022. We're in a brief lull right now, but that doesn't mean the issue is solved.

Via the Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget, here's what that looks like:

And during that time, the nation's already significant debt—the total amount that the nation owes—will continue to rise. In 2016, total debt held by the public will equal about 76 percent of GDP, which, as CBO notes, is "two points than it was last year and higher than it has been since the years immediately following World War II." This is a historic fiscal gamble.

This year's deficit tally was higher than expected for two essential reasons. In last year's omnibus, Congress passed a bundle of tax extenders without real offsets to pay for them, leading to lower than expected revenue, and, on the other hand, the growing costs of entitlement programs like Social Security and Medicare continue to be a burden. If you reduce tax revenues as spending continues to rise, the deficit will grow.

And a growing deficit, every year, is what we're headed for, with growing debt in tow. Between now and 2016, total annual deficits are expected to total about $9.6 trillion, all added onto the debt we're already carrying. And on our present course, that will only continue: In thirty years, the CBO estimates, debt held by the public will have doubled as a percentage of GDP, to about 155 percent.

This has always been the biggest problem with debt and deficits—not what's likely to happen this year or next, but the risks it holds further down the road. A growing, historically large debt means that the federal government is constrained a variety of ways: Because it's spending so much on interest, that means it can't spend the money on other programs (or return it to taxpayers in the form of tax cuts). It also puts the U.S. at risk of economic shock if interest rates rise sharply; the more debt a nation carries, the harder it is to weather a sharp hike in rates. That, in turn, makes a fiscal crisis more at least somewhat more likely—something that's especially worrying given that, thanks to the burdens imposed by high debt levels, policymakers will have fewer options if a crisis ever hits.

So while it's in some ways understandable that politicians have focused less attention on debt and deficits recently, it's also worrisome, for it shows how poor our political system is at managing predictable but long-term problems like this: The longer we wait to take action, the bigger the necessary adjustments will be, and the more difficult it will become, politically, to do so.

Show Comments (54)