Debate: 'Positive Liberty' Isn't True Liberty

Is the right to be left alone sufficient?

AFFIRMATIVE:

Libertarianism Is About Freedom From Interference

Brian Doherty

Political and ethical philosophers have expended millions of words trying to suss out what liberty means, how it should best and most coherently be conceptualized, and by what rules and institutions it is best secured. A decent summation of the purpose of political libertarianism is to limit unjust interference in people's lives and choices. By that standard, the only liberty consistently defendable is "negative" liberty.

Negative liberty means being able to make choices and pursue goals free from active interference via force or threat from humans or human institutions. "Positive" liberty is what you actually have the means to do.

If you lack the ability to take an action—such as travel, receive a certain type of education, or even eat—your positive liberty is restricted. But guaranteeing positive liberty requires making someone else provide it.

Demanding anything from another person other than that he refrain from actively preventing you from doing something requires interfering with that person's choices or property. By definition, providing someone with a positive liberty violates the negative liberty of one or more other persons. (Some find the "property" part illegitimate, but separating liberty and property denies political ethics' relevance to the lived human experience; even positive liberty proponents generally argue for the power to use one's property.)

The two concepts are contradictory: One cannot have negative liberty while ensuring most versions of positive liberty. Using the same word to describe them only introduces confusion.

Because the system we live in regularly violates negative liberty, many of us have "common-sense" intuitions that are troubling from a libertarian perspective. For example, people sometimes think that a restriction on people's lives doesn't violate their liberty if implemented via rules stated in advance and applied equally. Yet such restrictions by definition are "active interference by force or threat in someone's goals or choices."

Libertarianism, to be meaningful, must be a philosophy about the barriers other living entities impose on you. In a world of scarcity and poverty, in which unmet desires are endless, it can't coherently be about what you do or don't have the means to accomplish.

Late 19th century British political philosopher T.H. Green thought classical liberalism's vision of liberty was incomplete, claiming that absence of compulsion isn't enough to make a person free. Instead, Green wrote that true liberty required the "maximum of power for all…to make the best of themselves," disdaining negative liberty as the "freedom of savagery," of the lone nomad removed from civilization. This elevation of capability over noninterference was no mere academic matter, but rather laid the groundwork for an enormous amount of actual compulsion, as classical liberalism gave way to modern liberalism in the 20th century. This arcane "positive vs. negative liberty" debate shapes what sort of government people tolerate in ways that can make us more controlled by others' will.

There may be things you do not like about the current social order that have nothing to do with negative liberty. You might be bothered by income inequality, for example, and feel tempted to trade away some respect for property rights so the government can engage in wealth redistribution. But your concerns are no longer libertarian at that point.

It's also dangerous to place vague notions such as equality above liberty. If we never violated negative liberty, we'd have a very real kind of equality: the equal freedom to pursue our own goals, with no one, no matter how powerful, actively interfering with your life, even for their version of your benefit. But enforcing equality beyond that necessarily violates negative liberty.

One may value things above freedom when shaping the political and social order. But it seems un-cricket to wear libertarianism like a disguise, taking on the intellectual and emotional benefits that accrue to liberty, while actually valuing other things above the only truly coherent form of liberty.

There are many possible reasons for valuing liberty above other social considerations. We may see something inherent about human nature that demands we treat others as ends in themselves, not just as means to our vision of a "better" world; we may notice that the concept of "positive liberty" frequently dissolves into sophistical excuses to treat other people's lives as means to our preferred ends; we may think any overarching social vision of what "better" looks like isn't discoverable except by letting people demonstrate via free choice what they want; we may conclude on empirical grounds that empowering one group of people to make things "better" by manipulating everyone's lives and property inevitably leads to bloodshed, injustice, and misery; and to the extent that apparent goods arise from liberty-violating institutions, we may believe that a regime of negative liberty would be capable of providing those same goods without the bloodshed, injustice, and misery.

The concept of negative liberty has an emotional pull on nearly everyone in an abstract way, yet libertarians are acutely aware that most people are also willing to violate it to achieve something they want more. But abandoning negative liberty means allowing certain individuals to use force or the threat of same to make people who have not harmed anyone turn their will, their energy, their property, or their life toward someone else's goals. That this ought not be done is both a powerful intuition and, as libertarians try to argue, the key to achieving a world that is optimally wealthy and full of choices. This seems, at least to some of us, like as noble and appropriate a vision as a political ethics could have.

NEGATIVE:

Liberty Requires Well-Constructed Institutions

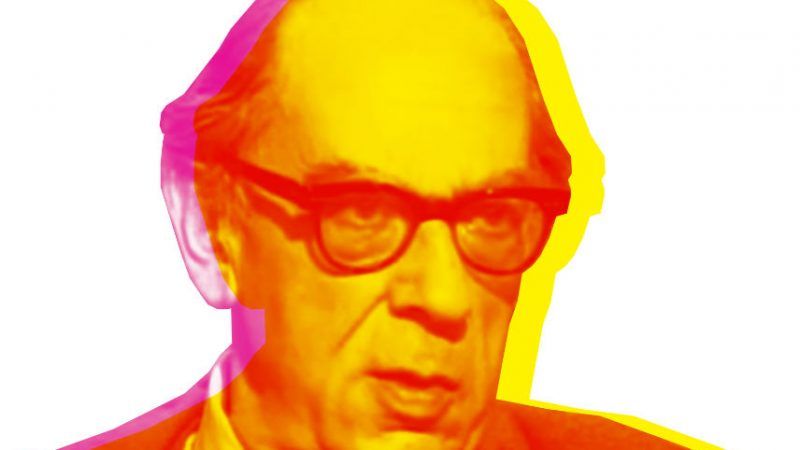

Samuel Hammond

The most influential works of philosophy do more to change how we think than what we think, and in turn they end up doing both. By this definition, Isaiah Berlin's 1958 essay "Two Concepts of Liberty" is very influential indeed. In drawing a clean distinction between "negative" and "positive" liberty, Berlin laid out a seductive vocabulary for thinking about our rights and freedoms that, once learned, is devilishly hard to transcend.

But transcend it we must. The popular view among contemporary libertarians that freedom means merely "freedom from," as in "freedom from the coercive tentacles of government interference," is radically incomplete. It takes for granted the immense institutional infrastructure that makes our apparent "negative rights" anything but, and it orients the libertarian reform agenda in a way that is ripe for abuse.

To see why requires tracing the origins of the negative conception of liberty back to its roots. As the economist F.A. Hayek notes in The Constitution of Liberty, "Not Locke, nor Hume, nor Smith, nor Burke, could ever have argued, as Bentham did, that 'every law is an evil for every law is an infraction of liberty.' Their argument was never a complete laissez faire argument, which, as the very words show, is also part of the French rationalist tradition, and in its literal sense was never defended by any of the English classical economists."

Instead, Hayek argued, the English classical liberals located liberty in "the evolution of 'well-constructed institutions' where the 'rules and principles of contending interests and compromised advantages' would be reconciled" in a way that channelled "individual efforts to socially beneficial aims."

Property rights and legal systems, in particular, represent what David Hume called the "artifice" of justice—institutional forms that, far from being absolute, primordial facts of nature, were adopted over time on the basis that they are empirically conducive to human flourishing.

This is not to underrate the unique threat governments pose to individual liberty. On the contrary, the positive underpinning of seemingly negative rights is what provides the meta-rule necessary for appreciating the why and how of limited government in the first place. From a commitment to the general, non-discriminating application of justice, to support for efficient institutions of property and market exchange and the recognition of essential civil rights, including political participation, that give voice to the voiceless: None of these essential characteristics of a limited, representative government can be found in the simplistic maxim of non-interference.

In contrast, consider what happens when the rationalistic view that "every law is an evil" is taken in earnest. Suddenly, ad hoc tax and regulatory breaks for politically connected companies—the definition of crony capitalism—come to be seen, in quasi-utilitarian fashion, as a sort of abstract reduction in society's net coercion (because they result in less total money being taken from, and restrictions being placed on, private entities), rather than obvious violations of equality under the law. Suddenly, it becomes a valiant form of civil disobedience to log-jam the state with frivolous legal disputes. And suddenly, otherwise careful thinkers like Milton Friedman proclaim to be "in favor of cutting taxes under any circumstances and for any excuse, for any reason, whenever it's possible," even if it ends up harming economic mobility.

Rationalism is infectious in all its forms, transforming rich normative concepts like liberty into easily parroted, disembodied axioms. That's why Hayek viewed rationalism as the ultimate source of tyranny, emboldening reformers to "fashion civilization deliberately," as if according to a blueprint. Modern libertarians recognize this tendency in romantic ideologies like Marxism, but too often fail to see it in themselves.

The alternative to a purely negative concept of freedom is necessarily, by process of elimination, going to be considered "positive." But this simply reveals the limits of Isaiah Berlin's dichotomy. "Positive liberty" is easily parodied as the notion that a rich man is more free than a poor man simply because he has greater resources and thus the freedom to do the things he wants, up to and including the "freedom to" make someone his slave. Besides being a paradoxical abuse of the English language, this view of positive liberty is held by virtually no one, save for the caricatures of bad-faith ideologues.

Much more fruitful is the idea that a truly self-determined choice has certain psychosocial prerequisites, be it a minimal level of health or education (what the philosopher Amartya Sen calls "basic capabilities"), or a reasonable set of better alternatives (such as the freedom from private power enjoyed by a worker for whom multiple employers are competing). Hayek highlighted the importance of competition, in particular, in his 1947 address to the Mont Pelerin society in which he called "the interpretation of the fundamental principle of liberalism as absence of state activity" as wholly unsatisfactory.

Hayek was right about this, as he was about so many other things. Competition, dynamic markets, and the benefits they spur in the form of wealth creation and innovation do not spring ex nihilo from the proverbial state of nature. So why should we, as libertarians, treat them as happy accidents of an otherwise negative creed? We should instead acknowledge that the case for liberty would be much weaker if flourishing was not among its fortuitous consequences, and we should look beyond dogmatic anti-statism to an agenda based on ensuring our institutions continue to reconcile competing interests and remain "well-constructed" for the 21st century.

Show Comments (128)