Debate: 'Positive Liberty' Isn't True Liberty

Is the right to be left alone sufficient?

AFFIRMATIVE:

Libertarianism Is About Freedom From Interference

Brian Doherty

Political and ethical philosophers have expended millions of words trying to suss out what liberty means, how it should best and most coherently be conceptualized, and by what rules and institutions it is best secured. A decent summation of the purpose of political libertarianism is to limit unjust interference in people's lives and choices. By that standard, the only liberty consistently defendable is "negative" liberty.

Negative liberty means being able to make choices and pursue goals free from active interference via force or threat from humans or human institutions. "Positive" liberty is what you actually have the means to do.

If you lack the ability to take an action—such as travel, receive a certain type of education, or even eat—your positive liberty is restricted. But guaranteeing positive liberty requires making someone else provide it.

Demanding anything from another person other than that he refrain from actively preventing you from doing something requires interfering with that person's choices or property. By definition, providing someone with a positive liberty violates the negative liberty of one or more other persons. (Some find the "property" part illegitimate, but separating liberty and property denies political ethics' relevance to the lived human experience; even positive liberty proponents generally argue for the power to use one's property.)

The two concepts are contradictory: One cannot have negative liberty while ensuring most versions of positive liberty. Using the same word to describe them only introduces confusion.

Because the system we live in regularly violates negative liberty, many of us have "common-sense" intuitions that are troubling from a libertarian perspective. For example, people sometimes think that a restriction on people's lives doesn't violate their liberty if implemented via rules stated in advance and applied equally. Yet such restrictions by definition are "active interference by force or threat in someone's goals or choices."

Libertarianism, to be meaningful, must be a philosophy about the barriers other living entities impose on you. In a world of scarcity and poverty, in which unmet desires are endless, it can't coherently be about what you do or don't have the means to accomplish.

Late 19th century British political philosopher T.H. Green thought classical liberalism's vision of liberty was incomplete, claiming that absence of compulsion isn't enough to make a person free. Instead, Green wrote that true liberty required the "maximum of power for all…to make the best of themselves," disdaining negative liberty as the "freedom of savagery," of the lone nomad removed from civilization. This elevation of capability over noninterference was no mere academic matter, but rather laid the groundwork for an enormous amount of actual compulsion, as classical liberalism gave way to modern liberalism in the 20th century. This arcane "positive vs. negative liberty" debate shapes what sort of government people tolerate in ways that can make us more controlled by others' will.

There may be things you do not like about the current social order that have nothing to do with negative liberty. You might be bothered by income inequality, for example, and feel tempted to trade away some respect for property rights so the government can engage in wealth redistribution. But your concerns are no longer libertarian at that point.

It's also dangerous to place vague notions such as equality above liberty. If we never violated negative liberty, we'd have a very real kind of equality: the equal freedom to pursue our own goals, with no one, no matter how powerful, actively interfering with your life, even for their version of your benefit. But enforcing equality beyond that necessarily violates negative liberty.

One may value things above freedom when shaping the political and social order. But it seems un-cricket to wear libertarianism like a disguise, taking on the intellectual and emotional benefits that accrue to liberty, while actually valuing other things above the only truly coherent form of liberty.

There are many possible reasons for valuing liberty above other social considerations. We may see something inherent about human nature that demands we treat others as ends in themselves, not just as means to our vision of a "better" world; we may notice that the concept of "positive liberty" frequently dissolves into sophistical excuses to treat other people's lives as means to our preferred ends; we may think any overarching social vision of what "better" looks like isn't discoverable except by letting people demonstrate via free choice what they want; we may conclude on empirical grounds that empowering one group of people to make things "better" by manipulating everyone's lives and property inevitably leads to bloodshed, injustice, and misery; and to the extent that apparent goods arise from liberty-violating institutions, we may believe that a regime of negative liberty would be capable of providing those same goods without the bloodshed, injustice, and misery.

The concept of negative liberty has an emotional pull on nearly everyone in an abstract way, yet libertarians are acutely aware that most people are also willing to violate it to achieve something they want more. But abandoning negative liberty means allowing certain individuals to use force or the threat of same to make people who have not harmed anyone turn their will, their energy, their property, or their life toward someone else's goals. That this ought not be done is both a powerful intuition and, as libertarians try to argue, the key to achieving a world that is optimally wealthy and full of choices. This seems, at least to some of us, like as noble and appropriate a vision as a political ethics could have.

NEGATIVE:

Liberty Requires Well-Constructed Institutions

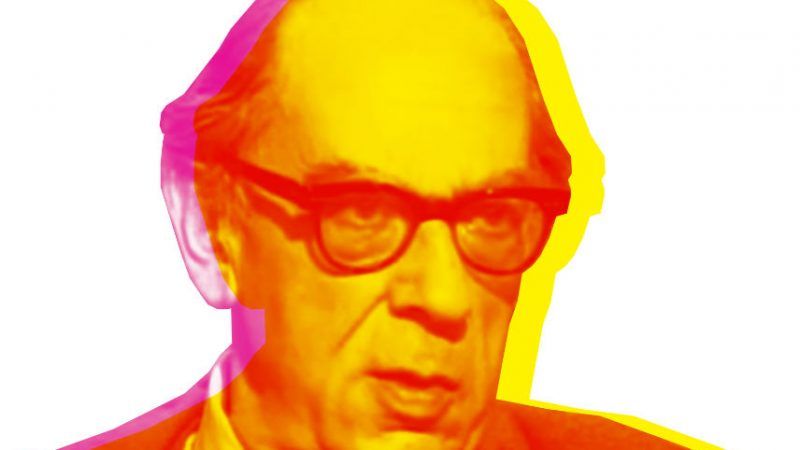

Samuel Hammond

The most influential works of philosophy do more to change how we think than what we think, and in turn they end up doing both. By this definition, Isaiah Berlin's 1958 essay "Two Concepts of Liberty" is very influential indeed. In drawing a clean distinction between "negative" and "positive" liberty, Berlin laid out a seductive vocabulary for thinking about our rights and freedoms that, once learned, is devilishly hard to transcend.

But transcend it we must. The popular view among contemporary libertarians that freedom means merely "freedom from," as in "freedom from the coercive tentacles of government interference," is radically incomplete. It takes for granted the immense institutional infrastructure that makes our apparent "negative rights" anything but, and it orients the libertarian reform agenda in a way that is ripe for abuse.

To see why requires tracing the origins of the negative conception of liberty back to its roots. As the economist F.A. Hayek notes in The Constitution of Liberty, "Not Locke, nor Hume, nor Smith, nor Burke, could ever have argued, as Bentham did, that 'every law is an evil for every law is an infraction of liberty.' Their argument was never a complete laissez faire argument, which, as the very words show, is also part of the French rationalist tradition, and in its literal sense was never defended by any of the English classical economists."

Instead, Hayek argued, the English classical liberals located liberty in "the evolution of 'well-constructed institutions' where the 'rules and principles of contending interests and compromised advantages' would be reconciled" in a way that channelled "individual efforts to socially beneficial aims."

Property rights and legal systems, in particular, represent what David Hume called the "artifice" of justice—institutional forms that, far from being absolute, primordial facts of nature, were adopted over time on the basis that they are empirically conducive to human flourishing.

This is not to underrate the unique threat governments pose to individual liberty. On the contrary, the positive underpinning of seemingly negative rights is what provides the meta-rule necessary for appreciating the why and how of limited government in the first place. From a commitment to the general, non-discriminating application of justice, to support for efficient institutions of property and market exchange and the recognition of essential civil rights, including political participation, that give voice to the voiceless: None of these essential characteristics of a limited, representative government can be found in the simplistic maxim of non-interference.

In contrast, consider what happens when the rationalistic view that "every law is an evil" is taken in earnest. Suddenly, ad hoc tax and regulatory breaks for politically connected companies—the definition of crony capitalism—come to be seen, in quasi-utilitarian fashion, as a sort of abstract reduction in society's net coercion (because they result in less total money being taken from, and restrictions being placed on, private entities), rather than obvious violations of equality under the law. Suddenly, it becomes a valiant form of civil disobedience to log-jam the state with frivolous legal disputes. And suddenly, otherwise careful thinkers like Milton Friedman proclaim to be "in favor of cutting taxes under any circumstances and for any excuse, for any reason, whenever it's possible," even if it ends up harming economic mobility.

Rationalism is infectious in all its forms, transforming rich normative concepts like liberty into easily parroted, disembodied axioms. That's why Hayek viewed rationalism as the ultimate source of tyranny, emboldening reformers to "fashion civilization deliberately," as if according to a blueprint. Modern libertarians recognize this tendency in romantic ideologies like Marxism, but too often fail to see it in themselves.

The alternative to a purely negative concept of freedom is necessarily, by process of elimination, going to be considered "positive." But this simply reveals the limits of Isaiah Berlin's dichotomy. "Positive liberty" is easily parodied as the notion that a rich man is more free than a poor man simply because he has greater resources and thus the freedom to do the things he wants, up to and including the "freedom to" make someone his slave. Besides being a paradoxical abuse of the English language, this view of positive liberty is held by virtually no one, save for the caricatures of bad-faith ideologues.

Much more fruitful is the idea that a truly self-determined choice has certain psychosocial prerequisites, be it a minimal level of health or education (what the philosopher Amartya Sen calls "basic capabilities"), or a reasonable set of better alternatives (such as the freedom from private power enjoyed by a worker for whom multiple employers are competing). Hayek highlighted the importance of competition, in particular, in his 1947 address to the Mont Pelerin society in which he called "the interpretation of the fundamental principle of liberalism as absence of state activity" as wholly unsatisfactory.

Hayek was right about this, as he was about so many other things. Competition, dynamic markets, and the benefits they spur in the form of wealth creation and innovation do not spring ex nihilo from the proverbial state of nature. So why should we, as libertarians, treat them as happy accidents of an otherwise negative creed? We should instead acknowledge that the case for liberty would be much weaker if flourishing was not among its fortuitous consequences, and we should look beyond dogmatic anti-statism to an agenda based on ensuring our institutions continue to reconcile competing interests and remain "well-constructed" for the 21st century.

Editor's Note: As of February 29, 2024, commenting privileges on reason.com posts are limited to Reason Plus subscribers. Past commenters are grandfathered in for a temporary period. Subscribe here to preserve your ability to comment. Your Reason Plus subscription also gives you an ad-free version of reason.com, along with full access to the digital edition and archives of Reason magazine. We request that comments be civil and on-topic. We do not moderate or assume any responsibility for comments, which are owned by the readers who post them. Comments do not represent the views of reason.com or Reason Foundation. We reserve the right to delete any comment and ban commenters for any reason at any time. Comments may only be edited within 5 minutes of posting. Report abuses.

Please to post comments

What a bunch of nonsense.

Indeed. Is the NAP itself a violation of negative liberties because it removes my right to murder and steal? This seems more like the kind of legal quibbling which lawyers have worked so hard to earn.

I call myself an almost-anarchist because I believe about the only valid purpose of government is to define terms such as "threat", and to establish a very minimal framework for redress of conflicts of self-ownership. However, this framework only applies to the people who agree to abide by it; everyone else can violate its redress framework at will, with the understanding that they also get no protection from it, ie, they cannot suddenly use it to complain about others who violate their self-ownership. Would this quibbler say I believe in positive rights at the expense of negative rights? That's a stretch.

So how do you protect yourself from people who don't opt in? They don't get your benefits, so surely it would be unjust to subject them to your rules.

You shoot them in the face in self defense, as they deserve?

They don't deserve it. They didn't sign up for your rules. This is just you murdering someone and saying it's OK.

I guess you didn't read the "self defense" part you fucking retard.

The right to ones life and to defend it is a natural one that you don't have to sign up for.

So is the right to modern healthcare. Prove me wrong.

Modern healthcare requires doctors and machines and medicines. You don't have "right" to force other people to provide those things for you. If so, they're your slaves.

It's the same as an automobile in that it (modern healthcare) has to be produced. Do you think everyone has a right to a car? I want a Porsche, a really fast one.

Does nature provide modern healthcare?

They don't deserve it. They didn't sign up for your rules.

Fuck off, slaver.

-jcr

There is only one human right, to not have force initiated against you. There is no right to murder and steal.

Sounds pretty tautological to me.

So?

As a non anarchist, I do believe in having a limited government, that fairly lays out a basic framework for laws, etc. However it should be very limited. Beyond that, it's pretty much all freedom from interference that matters.

Taken beyond the idea of a basic framework provided by government, one arrives at equality of outcomes. A completely impossible task. People are not equal. They have never been equal. They never will be equal. See Harrison Bergeron for a ridiculous look at what attempting this would entail. Anybody who tries to achieve the impossible is a fool.

I was born with a high IQ. I'm more math brained, so my writing is pretty garbage... But even my weakest intellectual skill, I'm better at than the average person. I have always been able to learn ANY task/fact/skill in a fraction of the time it takes most people. No government program can make an average IQ person capable of this. There is nothing to be done about it! I'm simply smarter than most people. They are doomed to be less mentally agile than me.

Now, a lower IQ person may well go on to achieve greater things than me. Plenty have. However their odds are lower. That's just the breaks. I also happen to be a little on the short side. Nothing can be done about that either. So I can never be as good at basketball as an NBA player, and most NBA players will never be able to absorb knowledge as fast as me. Any attempt to equal us out is DOOMED. So why try? It's nuts.

Positive liberty is a retarded concept.

In all your high-IQ dabbling you must have come across copious instances of liberal philosophers and politicians arguing for "equality of outcomes." Perhaps you'd like to list some here.

Let's see...

college admittance

professional hires

economic achievement

elected officials

incarceration rates

national park visitation

more?

More what? Nouns?

of what you specifically asked for and recieved you fucking retard

I asked for names of philosophers and politicians who endorse equality of outcomes. I'm sure there's one or two.

Thomas Paine comes to mind, you'd probably love Agrarian Justice.

The very term Disparate Impact means they are lamenting the absence of equal outcome, you raging dipshit

Every politician that advocates for "equal representation" for all people in their exact proportion of the population is demanding equality of outcomes.

Women choose to study engineering less than men... Yet it is demanded there be just as many female engineers at Google. That's retarded.

The fact that whites and Asians need higher grades and SAT scores, especially if they're also male, to get into the same school is not only discrimination... But it is enforcing an attempt at equality of outcomes.

It's all bullshit. And you know it Tony. So STFU.

The proper function of government is to defend individual negative liberty with the retaliatory use of force.

The State shouldn't do stuff.

More precisely, the state shouldn't give stuff.

Except cops and courts and prisons. But other than that!... oh and soldiers and tanks and ships, but no more giving!... well we also need limited liability and markets and contract enforcement... but, this is where the giving stops!

Libertarians really don't support any of that you fucking retard.

That's right! If government is gonna do SOME things it's only logical that it do EVERYTHING. Wow, you really got us there, buddy!

/sarc

Tony doesn't understand the concept of "limited" government. However, he does make an important point: We have big boatloads of government these days.

The state should not plunder.

Read up on Bastiats definition of plunder, Tony. Cant remember if it is The Law or Economic Harmonies.

Probably both, truth be told.

The function of government is to defend liberty.

Pretty good article

How did it get on Reason?

But in the end "don't tread on me"

The problem with "positive liberties" is that the concept, when the argument is carried to its logical conclusion, becomes a reduction ad absurdum. To wit, the story referenced by another commenter above, Harrison Bergeron. In order to enforce a positive liberty for an individual, the state must violate someone else's liberty. Free health care and education are not freedoms, they have to be paid for by taking something from someone else.

Equality of outcome is inherently in conflict with equality of opportunity, which is the goal of libertarianism based on nonaggression. Hammond's argument that liberty implies crony capitalism is just such a reduction to absurdity. Laws must exist to equalize opportunity, or "fairness" in the vernacular of our culture, which cronyism by state actors is very clearly and logically the opposite of.

Taking from someone else is unfair, whether done positively by taxation by government to "provide for the needy," or done negatively by giving tax breaks to connected cronies. Taxation to provide for the common good: the common defense and the stable political and physical infrastructure of a free society based on equal opportunity and treatment by the state. Free education and healthcare is not really "the common good." It is an "individual good," for the favored "needy" individual at the expense of the unfavored "rich." When you confuse the common good with good for the individual, you run into the logical absurdity so wittily illustrated by Kurt Vonnegut's memorable story, and so loudly espoused by modern leftists.

In order to minimize the logical pitfalls of state-enforced charity that "positive liberties" entails, we as a society and nation must balance the "fair treatment" of the needy with the illusory "unfairness" of keeping one's wealth. How much real unfairness toward the taxed individual will we tolerate in order to promote "opportunity for the disadvantaged?"

Eh, bullshit.

From the notion of property rights (exactly how do you own a piece of land that wasn't initially acquired through force) to oddly specific requirements as to what constitutes a just function of government (I never realized a mafioso protection racket was "Libertarian"); western libertarianism is an odd mix of personal mythologies and ad hoc reasoning after the fact. To wit- having nationalized healthcare is enslaving others to provide a service. Nationalized defense however; the soldier is somehow free. Riiiight.

The European tradition of Right to Roam perhaps typifies the contradiction, whereas simply having the right to move is core; western liberatarians unironically profess nope, having barbed wire everywhere and the right to shoot anyone who transgresses better serves the notion of liberty (speaking of reduction ad absurdum).

Non-zealots understand there will always be unease between positive and negative liberty, and there is certainly much debate to be had about what mixture best promotes maximum total liberty.

But the unique focus on negative liberty has just as many corollary contradictions and is quaintly pastoral in it arguments, unaware the rest of the world has moved on in complexity.

Excellent pair of comments. I would add that by their very nature, the impulse of both elected officials and unelected bureaucrats is to "Do Something," and the institutional bias of any organization is to grow and to protect itself and its turf. Therefore, the bias of the state, even one such as ours whose Constitution specifies both a carefully enumerated list of negative liberties based on natural law and an ingenious structure pitting the power of the state against itself in order to make state violations those negative liberties as difficult as possible, is overwhelmingly toward instituting "positive liberties" in pursuit of supposedly desirable outcomes.

Pushing back against this inertial force for the imposition of "positive liberty" at the expense of negative liberty is the core function of modern libertarianism. Equivocating about the role of "positive liberty" when the scales are so grossly out of balance in its favor is neither wise nor necessary. The left agitates quite well enough for the erosion of individual liberty without our help.

Annnd... disagree.

If all modern libertarianism has to offer is the requisite "all taxation is theft" admonishments, they have absolutely no say in crafting policy and leave it at the whim of those who don't have the concerns over positive liberties at heart.

Libertarians should be there to advocate for the least intrusive methods within a framework, and constantly point out ALL positive liberties come from what the economy can provide. If you want universal healthcare, then you also want an economy robust enough to provide it, and you want to administer it in such a way that doesn't hamstrung markets. If you want further taxation, you are essentially removing investment in what the economy can provide later on.

Libertarians have failed to take this into consideration, and instead have replaced slogans over considered thought on how to best proceed forward.

"Annnd... disagree."

Of course you do. Every leftist who trolls this site does.

"Libertarians should..."

Follow the dictates of leftists? Yeah... no.

"If you want universal healthcare..."

I don't. No libertarian wants this, certainly not the way you mean it. And leftists who call themselves libertarians as part of their schtick don't count.

Agree 100%. In large part I think the rationalism that American libertarians gravitate towards - both Rand and the Austrians are extreme rationalists - is a trap.

It creates the notion that if only one can form the perfect argument, that perfect things will just fall into place. And by ignoring the usually messy and often contradictory and uncertain world of empirical reality (and thus being incompetent at making any empirical case), libertarians become irrelevant in precisely those areas where what is needed is someone who IS focused on how to enhance liberty.

Even the default political/bureaucratic stance of "Just Do Something' is usually based on some empirical reality that doesn't fit neatly into a rationalist theory. What is needed are libertarians who can answer that 'do something' with actions that enhance liberty AND help resolve the issue. "Get Out of the Way" is a very valid form of "Do Something'. But you gotta know what you're talking about - and indeed understand the actual problem as well as those who advocate intervening and reducing liberty.

HEALTHCARE IS MUH RIGHTS = I will make slaves of Drs, Nurses, and Pharma/Device makers, until no more people freely choose to become those things

Where is my gay wedding cake in all this?

I'll mix up the batter and you lick the beater?

If you lack the ability to take an action?such as travel, receive a certain type of education, or even eat?your positive liberty is restricted."

The term Positive "Liberty" used in the same sense of the term Negative "Liberty" is a contridiction and isn't a real thing. That's using 2 completely different definitions of the word Liberty. Basically using semantics to great a false equivalency. As long as no one is stopping you from traveling on your own accord, acquiring sustenance, or education yourself you're Liberty is not being infringed. You're lack of ability to do any of those things has nothing to do with "Liberty" by that same "definition" of liberty. Not allowed to is not at all the same thing as not able to even though you could technically call both a lack of "freedom" as in I am not "free" to buy a mansion in Hawaii. Why you're not "free" to designates Liberty versus ability.

I wrote this before I noticed there,was a page 2. I do see that you touched on this point.

It's no surprise you shot your wad too soon.

You really need to stop talking to your mom about her sex life.

We are open-minded and like to share a good laugh.

The legitimate purpose of government is to protect our rights. I supposed the important question is what rights are--what is it that legitimate government is protecting?

A right is the obligation to respect other people's choices, and rights, therefore, arise naturally as an aspect of agency. A comet hurling towards the earth has no rights because it has no agency. It's only a victim of the physical forces acting upon it. Other people aren't like comets. Because they have agency, we are obligated to respect their freedom to make choices for themselves, i.e., they posses rights.

Examples of legitimate government, for instance, include not only police to protect our rights from criminals but also criminal courts to protect our rights from the police. We have a military to protect our rights from foreign threats--not only terrorists, e.g., but also foreign governments. In all cases, we're talking about the government protecting our rights from something, and in some of those cases we're talking about the institutions protecting our rights from itself. We're talking about negative liberty.

There is only one human right, to not have force initiated against you.

A right is the obligation to respect other people's choices, and rights, therefore, arise naturally as an aspect of agency.

In the day-to-day world, that means what, exactly? Nothing resembling that description of a right ever happens.

Here is an alternative description of a right which does describe what happens in the real world, all the time: A right is a limited and defined power, vested in an individual natural person, to stay the hand of government.

As realistic as that second definition is, libertarians don't like it. They don't like it, first, because almost no individual person enjoys that kind of power, so it has to be vested in the person, and defended on his behalf, by some agency with more power than government. That agency is the national sovereign, which created the government, and therefore has the power to limit the government?which the sovereign has done by decreeing the right. Second, and alas, it offends libertarians because they hate the notion of sovereignty. They hate it most for its ongoing, remorseless, day-to-day refutation of their proof-against-evidence insistence that axioms and pure reason will someday triumph over power and experience.

Is that triumph likely? Might it be worthwhile to re-consider an ideology so radically committed to an ideal of which history and experience provide not a single successful example? What Is libertarianism? Is it even a theory of government?

"In the day-to-day world, that means what, exactly? Nothing resembling that description of a right ever happens."

Rape is a crime because the obligation to respect the victim's right to make choices for herself was violated.

Theft is a crime because property rights are the right to make choices about who uses something, when it's used, how it's used, etc.--and we're all obligated to respect the rights of others.

Freedom of religion is the right to choose your own religion.

Freedom of speech is the right to choose what you say.

Gun rights aren't the right to indiscriminately shoot people. They're the right to choose to own and carry a gun.

If no one's right to make choices for themselves was violated, then there was no legitimate crime.

Laws that compel people to do things against their will have no legitimate basis in reality apart from the idea that "might makes right".

Our obligation to respect the rights of others exists independent of and separately from the government whose only legitimate job is to protect our rights.

That's the sort of thing this means in the day-to-day world.

Ken Shultz, I appreciate your effort to illustrate with examples. Here is the part I find hard to follow. It isn't enough to define crime. It has to be restrained and punished. Just defining a crime does nothing to prevent it in the first instance, nor to punish it, nor to prevent its recurrence, nor to thwart its increase.

Likewise with defining rights. Isn't that a mere philosophical exercise, absent some ability to vindicate the rights defined? Nothing in your answer even suggests how to do that. You do see that, don't you?

Sometimes, it seems that libertarians suppose the great difficulty in politics is that too few people are clever enough to follow their reasoning. That isn't really so. Libertarian reasoning is readily mastered by typically-bright adolescents. Many folks who disagree with libertarians do so with good understanding of libertarian reasoning.

The problem is more fundamental, and more elusive. It has to do with various assessments of the question to what extent politics can be served by choosing among reasoned solutions, experience-based solutions, or aspirational solutions. Add to that the difficulty of accommodating differences of opinion among political participants with regard to the former assessments. Very little of that is amenable to methods based on pure reason.

"Isn't that a mere philosophical exercise, absent some ability to vindicate the rights defined? Nothing in your answer even suggests how to do that. You do see that, don't you?"

We have police to protect our rights from criminals. We have criminal courts to protect our rights from the police. We have a military to protect our rights from foreign threats. We have civil courts to protect our property and contracts.

The legitimate purpose of government is to protect our rights, and theses are the kinds of ways that the government does that. I see these examples as quite realistic and pragmatic--even though they're predicated on some rather theoretical principles.

Take mens rea for example. I'm not sure all twelve members of a jury need to grok that criminals willingly forfeit some of their liberties when they willfully violate someone's rights--so a crucial part of a jury's job is to determine that the defendant intentionally did what he or she did (AKA "mens rea"). Every member of the jury need not grok that because government cannot violate people's rights, the determination of someone's criminal guilt must be deliberated by a jury of civilians, rather than the government. It's probably enough for them to determine that the guy holding the smoking gun was in fact the murderer. And that's fine. How much more pragmatic realistic do I need to be?

You know what's not realistic? Squandering trillions of dollars for decades throwing millions of adults in prison for buying, selling, and consuming cannabis. Ten years ago, people used to look at us like we were idealistic dreamers for thinking that absurdity would end someday.

It's the people who imagine that other people's rights can be artistically violated without negative consequences that are being unrealistic. And it's their lack of understand of the principles by which the real world operates that leads to so much unnecessary suffering in the real world. In short, my solutions are not unrealistic, and spreading the libertarian gospel is pragmatic as fuck.

It's relevant to point out that when government institutions fail (not in theory but in real life), it's because they failed to protect people's rights from something.

The USSR and Venezuela failed because, among the failures to protect other rights, they failed to protect property rights--the right to make choices about who uses property and how it's used, etc. Other governments and institutions--from ISIS to the Holy Roman Empire--failed because they failed to protect other rights. Note that all these failures are the result of governments and institutions failing to protect people's rights from something--sometimes themselves.

If the institutions charged with protecting our rights are themselves subject to failure when they fail to protect people's rights from something, then surely we're living in a world where the forces of negative liberty predominate.

It's relevant to point out that when government institutions fail (not in theory but in real life), it's because they failed to protect people's rights from something.

Do you mean to suggest that government can fail in no other way? For instance, can government fail by being over-protective of individual rights, including property rights? Arguably, that is why the Articles of Confederation government failed in 18th century America. Assuredly, failure to protect people's rights was not the cause in that case.

I wouldn't say that governments can fail in no other way. Ancient societies collapsed because they weren't familiar with the problems associated with intensive farming, because they were exposed to new diseases, because of natural disasters, etc.

That being said, governments cannot violate our rights without suffering the negative consequences of doing so. The obvious examples of the USSR and Venezuela failing because of their failure to protect property rights are obvious examples, but violating other rights doesn't come without negative consequences either. ISIS and The Holy Roman Empire during the Thirty Years War both failed because (among other things), they failed to protect people's right to choose their own religion.

"As a zealous Catholic, Ferdinand wanted to restore the Catholic Church as the only religion in the Empire and to wipe out any form of religious dissent. The war left the Holy Roman Empire devastated, its cities in ruins"

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/F.....an_Emperor

That isn't what happened during Shay's Rebellion, which led to the end of the Articles of Confederation.

If the federal government had put down Shay's Rebellion, that might have been an example of the government failing to protect the rights of creditors. That the federal government was able to put down the Whiskey Rebellion might not be a good example of protecting the rights of creditors. It was more like the federal government demonstrated the ability to impose taxes at the point of a gun.

I butchered that.

"If the federal government had [NOT] put down Shay's Rebellion, that might have been an example of the government failing to protect the rights of creditors."

Now it's fixed.

Easiest historical example is the antebellum civil war US. Every major event from the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850; to Bloody Kansas; to Dred Scott; to the Southern planters perceived loss of power (exemplified in the King Cotton speech); to the Barnburners/Hunkers conflict that led to the breakup of the Whig/Dem duopoly.

Those are all examples of a society that is falling apart and failing. Precisely on a conflict of rights and liberties. We all know where it led - but we don't often study those events in themselves without hindsight bias or historians fallacy or presentism.

If we can't study those familiar events as they actually were - chances are, we can never make any informed analysis as to why failures happen with less familiar events

This article was a nice change. Thanks, Brian and Sam.

Disagree - I only want to read articles related to Twitter drama.

Perhaps it comes down to what we owe to the accepted Institution. If we owe behavior, such as not murdering or delivering on a valid contract, we have a (negative) liberty-based society. If we owe stuff, whether royal tribute or income tax, we do not.

(And those of us in favor of true liberty have to change this language of positive and negative since these unfortunate terms have already determined preferences for most people.)

OT: Eat a burger, losers.

The employees should stop using their home country's tap water to rinse the lettuce

You're the Christopher Cantwell of Reason commenters.

I was talking about McDonald's Canadian employees and their disgusting poutine water. If that makes me a Nazi, so be it

Whatever you say, Irma Grese.

Instead, Green wrote that true liberty required the "maximum of power for all...to make the best of themselves," disdaining negative liberty as the "freedom of savagery," of the lone nomad removed from civilization.

So where the hell's my aircraft carrier, tactical nukes and my army of slaves?

There's a fine line between what you owe for common goods like roads, national defense, police and courts and so on that create a civilized society fit to live in and what's taken from you to provide for the parts of society that you don't use, don't need, don't want. There's an argument to be made for your moral obligation to help your fellow man, but there's also just as compelling an argument that calling charity an entitlement and enforcing contributions at gunpoint is an immoral act that leads to immorality in the recipients of such charity.

I mean, have you ever received a "Thank You" card from a welfare recipient? No, you haven't, because this positive liberty bullshit has taught charity cases that they're entitled to charity, that the rest of us owe them something simply by virtue of the fact that we both exist. That's an evil and immoral thing to teach people because what incentive do they have to improve their lot by their own initiative if the world owes them a living? You're creating slaves with a slave mentality rather than human beings who value their self-ownership.

OT: Hey libertardians, the Neo-cons were right!

The second guy covers the flaws in the negative liberty concept pretty well, but it's important to realize that it's fatally flawed by such caveats as I have highlighted. If your whole moral structure depends on immediately stating an exception to it, that's pretty flawed.

That isn't an exception you fucking retard.

The argument that depending on charity isn't sufficient to care for the needy is an odd one - isn't government just the things we choose to do together? If everybody's willing to let government provide for the needy, surely they're just as willing to voluntarily contribute the same to private charities, right? (Obviously if government has to force you at gunpoint to contribute to their charity, government is not in fact "the things we choose to do together", it's "the things that some people are willing to force other people to do".)

If you go back to the days where there were workingman's associations, you had a voluntary cooperative insurance/charity scheme - if you were a carpenter you joined a carpenter's association that provided benefits in training and education and employment opportunities and cash in case you got sick or injured. Of course, how much they were willing to help you depended on how good a person you were, if you were a drunken wife-beater who never tried to better yourself you weren't getting as much help as somebody more dedicated to hard work and clean living and self-improvement.

Now voluntary charity might not be enough to provide everybody everything they need, but it doesn't cost anybody a dime they're not willing to pay. Government does a much more thorough job of helping the needy, but at a cost of hundreds of billions of dollars taken by force, so which one is really better? There's always trade-offs.

Also, there's this thing called "moral hazard".

There are lazy suburban white kids who might never make anything of themselves if their parents hadn't effectively kicked them out of the house at some point, and that problem (and its solution) is by no means confined to suburban white kids.

Millions of immigrants have come here with little or nothing since the 1960s and built prosperous lives for themselves.

Meanwhile, millions of native born Americans sat on their asses and did nothing but perpetuate poverty across generations--in no small part because the good intentions of enough voters enabled them to do so. It's much like a parent who coddles their child into his 30s--we're not necessarily doing these people or their children any favors by rewarding their misbehavior inactivity.

Yes, perhaps ethics matter more to create and support voluntary associations. And I think ethics provide the secret sauce that makes the progressive holy grail of scandinavian socialism work. A communal system that contains a strong work ethic, and does not tolerate slackers and deviants, might just pull it off. That and (in the case of Norway and to some extent Denmark) a shit load of oil money.

As I wrote in another thread there are 3 ingredients to a functional and then prosperous society.

1. Rule of law

2. Equality under the law

3. Property rights

That these Scandinavian countries can be relatively successful is because while they may be middling in property rights, they are very strong on the first 2 ingredients. A country such as ours that is good in all 3 will prosper more. What is sad is that if we were great in all 3, nobody would be comparing us to Scandinavian countries because we would be that far ahead.

While I agree that your three ingredients are essential, I do not think they are sufficient. Again, without some broad drive and initiative, i.e. "work ethic", a society can have a functioning and fair legal system that upholds property rights, but be far from prosperous. I still think the Scandinavians have achieved reasonable prosperity mostly because they work hard and don't tolerate bullshit.

I disagree. In that case it is only a matter of time until the culture changes. I think work ethic is largely a function of property rights, which remember, the Scandanavians are really not that bad on. Maybe I'm wrong on that, but it seems historically to be the case.

Culture is often slow to change. If the Scandanavians move towards being poor on property rights, I think you will see that work ethic change within a generation or two.

Great job channeling your inner Paine and Burke, guys. Enjoyed this article!

Outstanding piece!

MOAR OF THIS PLZ!

Agreed. Hate the term positive liberty/rights. They are not. The more appropriate term is entitlements.

Positive liberty isn't.

Who wrote this drivel ?

Ja mama.

Positive liberties require you to construct a relationship between two people, potentially against the will of one of those people thereby denying that relationship a basis in consent and replacing it with force. Negative liberties do not do this. Positive rights, if they are true, must be universal. As such, a person living in China who has never even contemplated the existence of a particular person who lives in Chile is bound to that person ONLY by the nature of that OTHER persons circumstances in life. If the Chilean is in need of something, and that thing can be supported by positive liberty rational, then the Chinese person is now compelled, regardless of his consent or lack there of, to be bound to this other person absent anything HE did. HE is innocent of any action towards the Chilean, but is on the hook to make whole the Chilean. That is a perversion of justice. If it were true, then in any court in the world, you would not have any moral need to attempt to find guilty the guilty party of an infraction. Any person in the human construct of positive liberty rational will do. Take the first person you find on the street, throw them in the the court, and declare that the taking of their time, energy, property, etc. is just even in the face of their non-consent and even in the face of their known and obvious innocence. If positive liberty is real, then there are no innocent people in jail.

Prior to any institution you have the state of nature in which two people are free to expend all their physical abilities running, building, etc. unrestrained. Eventually their bodies or their plans will collide. Rights will not serve as a force field, but merely as a measuring stick to adjudicate who, if anyone, has been wronged. Given that consent is where legitimacy arises, then the person who was acted upon absent their consent was wronged. This concept denies the possible existence of positive rights.

Positive rights simply take a giant dump on consent and replace it with "it's moral because FYTW"

Do you have any opinions on no-fault auto insurance? Isn't it another perversion of justice?

If I understand no-fault auto correctly (I haven't stayed in a Holiday Inn Express in quite some time)... The insurance company has agreed to pay you despite no one being found guilty of causing a harm to you (initiating force, even accidentally). They agreed to transfer you some of their property if certain conditions are met. They will make this agreement with you in exchange for your transfer of property in smaller increments over time.

As such... it is still all built on consent. You consent to the policy, the insurance co. consents to the policy. You are the only two parties involved in a transfer of property.

Now... that doesn't necessarily absolve the person who hits you in terms of "justice." Your contractual agreements with a third party do not bear on the restitution owed to you by the aggressor. Negative rights still allows us to conclude that the person who hits your car has committed a wrong in some fashion (maybe accidentally) and restitution is owed you by THEM for there to be justice. You may, because of your policy, consent to not giving a damn if they pay you or not. But if you consent to them not paying you, then you have stated that you have been made whole and that justice has been met.

Healthcare is a right! And so is the college education that taught me this is so.

Now... hand over your wallet. And don't make any sudden moves.

The notion that positive liberty (entitlements) should not exist (i.e. 100% adherence to the NAP) makes you an anarchist, by definition, and is problematic for libertarians believing in a limited government.

I'd likely be an anarchist if I believed it could work, but I'm convinced it would lead to either antagonistic tribalism or, worse, getting thumped by an existing nation-state, thus ceasing to be free. So where does one draw the line on entitlements?

Here is my take (and it's a work in progress):

The primary tenet should be to maximize liberty for all.

If you believe, as I do, that accomplishing that requires a government (after all, you have no liberty when your property is invaded), then you need to set up a government dedicated to that primary tenet and nothing more. It follows that the line is then drawn where the government may provide you with nothing beyond the protection of your negative rights/liberties. IOWs, the only entitlement you have is the guarantee of your negative rights.

SO:

Maximization of liberty for all...

1. A person may do as they choose, PROVIDED they do not infringe upon the rights of another (the NAP).

2. The ONLY legitimate function of government is to protect the negative rights of individuals.

(Yes, I realize that 2 violates 1 and am open to a better solution)

Fire away

Everything you wrote is good until "It follows that..."

Liberties are certainly not maximized by the night-watchmen government you describe. A government that redistributes resources optimally is what maximizes liberty. Nothing about a night-watchmen government prevents mass poverty and the accumulation of wealth by a tiny few. That is not a state of affairs in which freedom is maximized. It is concentrated in the hands of people who can only stand to gain or lose minuscule amounts of freedom, while most people could gain enormous amounts of it with modest transfers of wealth to them.

Bullshit. As long as those rich people did not hire private armies to take the harvest from the poor, down-trodden peasants, too bad. If a bunch of twits want to major in gender studies or binge drinking/smoking, and then discover that the market does not value their "product", they don't get to claim mine.

I thought we were talking about maximizing freedom.

"A government that redistributes resources optimally is what maximizes liberty."

Optimally by whose definition, Kimosabe? What constitutes optimal will vary from person to person.

"Optimally by whose definition, Kimosabe?"

Let me guess... by the person who's arguing that a government that redistributes resources optimally is what maximizes liberty.

You don't understand. Socialism works; it just hasn't been tried by the Right People yet.

Tony is the Right People. Just ask him.

And of course, Tony will have to hire people with guns to enforce his edicts. His society would most certainly not be free.

The argument for "positive liberty" when made with a straight face in spite of of the economic reality of scarcity always boils down to the Orwellian logic of "freedom is slavery."

By that measure, and that measure only, would Tony's ideal society be free. Of course, Tony is a moron, so he never makes his argument quite so coherently.

David K, that remark will be hard for Tony to argue around. It confronts his implication that there is some objective way to measure and optimize liberty, when of course no such method exists, or can exist. Too much of politics is contingent, subjective, and mutual ever to do such a thing. People at large cannot even agree what liberty is, let alone measure it.

Alas for libertarians, that critique applies alike to their entire intellectual edifice. What can't be measured for an anti-libertarian cannot magically be transformed, and deliver useful measurements for the purpose of justifying libertarianism.

Any claim also fails that it doesn't matter?doesn't matter because under libertarianism each individual determines the political outcome most satisfactory to himself. That amounts to a claim to extend a power of judgment to libertarians that is not only withheld from others, but must be withheld, lest they use that power to reach anti-libertarian conclusions, and implement them through politics.

What you have there is a sharp criticism of political arguments based on pure reason, from which uncertainty, contingency, mutuality, and experience have been purged. Think about that carefully, because among political philosophies generally, libertarianism is the one most challenged by that critique.

Liberties can not be "maximized" as they are not quantifiable. One either has NOT had their rights violated... or they HAVE had their rights violated. You can not increase the number of people who's fundamental rights have not been violated by violating their rights. That is an absurd concept.

Lol wut.

He is arguing for violating their rights less often than currently, all the way to the point where society can still function properly. That is quantifiable and a net increase in liberty.

Liberty doesn't guarantee the absence of poverty. You have the freedom to fail. Also the freedom to be a lowlife layabout.

How you can possibly conceive of yourself as having any Libertarianish tendencies, while advocating "optimal Government redistribution" is truly mind-bottling.

Go play in traffic

If people are allowed to enter into an arrangement whereby defense of rights is carried out on a contracted basis you can still have a shared pool of resources to maintain security of rights. Think mercenaries. Thus, you can achieve the end (security of rights) without the need of a state (violation of rights).

Anarchy by its dictionary definition is literally no government. Anarchy in philosophy is no government... that prevents you from leaving its jurisdiction and that imposes its edicts upon you even in the face of boundaries of property.

In an ancap society you would be free to join with others and agree to certain norms where failure would be met with force either by the victim or the few employed to act on behalf of the victim. Those employees do not have to be "the state." These employees would enforce the agreed upon edicts which may go beyond "negative rights" only AND may also serve as a means to defend negative rights from anyone outside the agreement as well. They can do this because they have been contracted to be an extension of YOU and YOUR rights... which you do not lose simply by agreeing to have someone else serve as a tool for you to defend your rights. The person you hire is no different than a gun in your hands... simply an extension OF YOU, not a REPLACEMENT of you or your rights.

Show me The New Anarchist Man, or at least how you deign to come to that evolution of human nature.

Marx's end utopia was anarchy. Funny that, isn't it? What happened instead? Dictatorship. What happened in the French Revolution? Dictatorship.

Human nature stands fully in the way of anarchy. It always has, and always will. The libertarian understands this, the anarchist does not.

Your silly daydream makes no account for

a) The Commons i.e.The Tragedy of The Commons - who gets to decide when and where a river is dammed, or diverted for irrigation, or where you can hunt or fish or log or mine, or how your garbage and effluent impacts those down the hill or down the river...

b) What happens when your "victim" is unsuccessful in meeting wrongs with force.

You essentially believe in Might Makes Right, and warlords (yes, that cliche, but it's exactly what you describe), and dictatorship of the Strongest

In an ancap society you would be free to join with others and agree to certain norms where failure would be met with force either by the victim or the few employed to act on behalf of the victim. Those employees do not have to be "the state."

All I can say in reply is that when your "few" meet my "few" to settle differences, I want my "few" to be several times less-few than your "few." How do you suppose that reasoning ends? Or how many iterations it can go through?

sparkstable, that is a loopy, aberrant, vision. If anything distinguishes it from psychosis, it is only its mode of thought?an extreme application of pure reason, absent any reliance at all on experience.

I have a friend who is a therapist. She tells me she encounters this kind of thing from time to time. She calls it "extreme thinking," to avoid giving it a more stigmatizing label. It sometimes helps, she says, to ask the patient, "Assuming everything you say is true, what do you suppose is going to happen to you, if you insist on going around saying that to everyone?"

That should help, unless you have no theory of mind at all. But if you don't, then you may actually be psychotic.

My best friend is a psychologist. He tends to agree with my assessment of things... assuming things are real to begin with. Given that he actually knows me and finds me healthy I will trust him over your attempted analysis simply because you know a therapist. She may be great... but you aren't her.

Also... you are essentially arguing for pragmatism. That the ends (you FEEL safe because of the state [how safe do victims of cops or war feel?]) justify a violation of rights. My argument is not one of pragmatism but of right and wrong. You are essentially saying that to preserve rights you have to violate them. And I am making absurd claims?

You essentially want to live longer at the expense of others and then say that I am the one promoting might makes right. You may want to have that plank in your eye checked out.

sparkstable, what do you suppose is going to happen to you, if you go around saying that to everyone?

That's the bad part of a free society: you can't force people to do what you want them to do. Right, Tony?

Presumably you define a free society as one with a government that focuses most of its attention on shooting and caging people.

No, that is the kind of government that you favor, if you don't get your way.

I like the way that Jonah Goldberg puts it:

Hold on thar! Why do we have to talk about guaranteeing liberties? Guaranteeing either positive or negative liberty requires extracting something from others.

Why not just discuss the desirability of liberties, and how to increase them, rather than (impossibly) guaranteeing them? In that case, isn't it obvious the only value of negative liberty is in increasing the amount of positive liberty? Negative liberty is merely instrumental to positive liberty, & positive liberty is merely instrumental to other things.

Positive liberties only guarantee one thing... a violation of someone else's negative liberties. Negative liberties only guarantee one thing... the ability to determine if an act was morally right or wrong. Rights are not force fields... they are concepts of being that allow us to determine good from bad. Only negative liberties allows us to do this without committing a contradiction.

sparkstable, I get that libertarians don't think much of the liberty of self-government?hate it, actually, and deny it even exists. What I don't get is by what mental process libertarians convince themselves that other folks' views on self-government don't count, and can be violated without any negative moral implications at all. Indeed, libertarians, inexplicably, seem to regard violating others' rights to self-government as virtuous. Whatever libertarians might conclude, pretty much everyone else will see that as a contradiction.

So the guy who says he wants to violate some rights is a champion of liberty? You seem to be an incredibly smart person with zero grasp of words and their meanings.

Example... a libertarian says people should be free. You hear "libertarians hate freedom!" Um... what?

You think libertarians are telling you what rules you have to live by thereby negating your ability to self rule when they simply tell you yo leave them alone?

A libertarian is simply saying you can't use force on people except in defense. That's it. You want healthcare? Great! Go get it! Just dont enslave others as your means of doing so. Dont rob from people as your means of paying for it. You want a communal society with your friends? Go for it! Just dont force others into your system when they decide that being expropriated from isn't a good idea.

Okay, busted. I wasn't entirely forthright. I do get by what mental process libertarians convince themselves that other folks' views on self-government don't count. It is a mental process from which all others' moral judgments can be excluded as unworthy, because pure reason demonstrates the manifest superiority of the libertarian's moral judgment. And happily, the libertarian's moral judgment is assured to conform closely with the libertarian's self-interest. More happily still, pure reason applied by others is bunk.

Or maybe I was forthright, and just needed the example of your comment to provide insight.

Nope. For details see this essay.

Excellent article--thanks for the link. I would add that the whole idea of "positive rights" is really just an emotional appeal to justify leftist power grabs. The fact is, as long as resources are scarce relative to demand, which would seem to be the reality for the foreseeable future, "positive rights," and by extension, "positive liberty," is a collectivist fraud perpetrated on a gullible electorate.

How can you guarantee negative liberty w/o extracting something from somebody?unless it's the guarantor who pays up? There's no way you can be certain somebody won't violate somebody else's negative liberty, so the only way to guarantee it is to have a warranty fund to pay for that violation, & that fund would either have to be extracted from someone or paid by the guarantor.

Do you mean law enforcement? It has many failures & costs.

Positive rights require the initiatory use of force which violates the NAP and makes them immoral.

A lot of folks are going to tell you that violating their right of self-government violates the NAP. That's actually what the founders told the British, by the way.

The only way to violate the NAP is to initiate force. A government that refrains from doing so CAN'T violate the NAP.

So explain to me, taking the American Revolution, from its earliest stirrings to The Treaty of Paris, which side initiated the use of force? Surely you do not suppose a logical impossibility, that somehow, both sides initiated the use of force? If not, please tell me which it was.

While you are at it, tell me which side the tories would choose for blame, which side Ben Franklin would choose, which side the British parliament would choose, which side American Indians would choose, which side Thomas Jefferson would choose, which side American slaves would choose, which side George Washington would choose, as the initiators of force. As a libertarian expert on the NAP, that ought to be a slam dunk for you.

Note: I'm not looking for an answer based on retrospective reasoning. I'm looking for an answer based on experience, using historical citations to sort these questions, and prove by evidence and reason which party violated the NAP. Give me your historical citations showing which side initiated the use of force. Don't make yourself ridiculous by suggesting you can reason from libertarian principles to discover the facts of history.

And if you find that task difficult, with the facts laid on the record before you, how much more difficult?difficult to the point of uselessness?will it be to perform the same analysis prospectively, for events which are only incipient, and yet to occur.

As a matter of politics, as opposed to philosophy, of what use is the NAP?