Actively Open-Minded Thinking About Climate Change

It's not really all that open-minded. Science curious people on the other hand ...

Americans remain deeply divided along partisan lines on the issue of climate change, according to a new Pew Research Center poll. Seven in 10 liberal Democrats trust climate scientists to give full and accurate information on the causes of climate change, whereas only 15 percent of conservative Republicans do. In addition, 54 percent of liberal Democrats believe that climate scientists have a good understanding of the causes of climate change, compared to only 11 percent of conservative Republicans. Liberal Democrats also believe that climate research reflects that best available evidence most of the time. Only 9 percent of conservative Republicans agree.

Why this partisan difference over what is essentially an empirical question? Some researchers have concluded that conservatives are less likely than liberals to be open-minded or to engage in effortful cognition when evaluating scientific evidence, especially when accepting those data means undermining their faith in free markets. But research from the Yale Cultural Cognition Project supports a different notion: This polarization tends to occur when accepting or rejecting a scientific thesis becomes a signal to your fellow partisans that you're on their side.

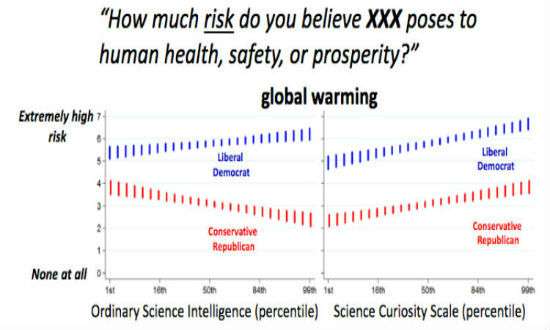

For example, research by the Yale law professor Dan Kahan finds that as scientific literacy goes up, so too does partisan polarization on the issue of climate change. In other words, the more science people know, the more they are able to seek out and find information justifying their beliefs.

In a new study, Kahan and his colleagues assess the relationship between accepting the evidence for man-made global warming with a measure for actively open-minded thinking and attitudes toward climate change. Actively open-minded thinking is defined as the "willingness to search actively for evidence against one's favored beliefs, plans or goals and to weigh such evidence fairly when it is available."

In a survey, some 1,600 Americans were sorted by political orientation and their propensity toward actively open-minded thinking. Psychologists have devised various questionnaires that aim to measure an individual's propensity to engage in such salutary cognition; Kahan's survey used a seven-item scale that asked participants to rate their agreement with such statements as "allowing yourself to be convinced by an opposing argument is a sign of good character," and "changing your mind is a sign of weakness."

In the past, many researchers have argued that political conservatives tend to be deficient with regard to actively open-minded thinking. Consequently, they contend that if for some odd reason a conservative did have such a disposition, he would be more likely to accept the scientific evidence in favor of climate change. In fact, the opposite occurred.

Since most liberals in the survey already believed that there is solid evidence of recent global warming due mostly to human activity, their probability that that they would accept that conclusion rose only modestly with higher actively open-minded thinking scores. On the other hand, the higher conservatives scored on actively open-minded thinking, the lower the probability they would agree that there is solid evidence for man-made global warming. The gap between liberals and conservatives on beliefs about climate change widens the more that both engaged in actively open-minded thinking.

What is going on? The researchers argue that "actively open-minded thinking in fact enhances the proficiency of reasoning aimed at forming identity-congruent beliefs." Actively open-minded thinkers are "simply better at screening information for identity-congruent inferences." In other words, sophisticated reasoning skills enable people to more easily find and espouse information that indicates their loyalty to their political affinity groups.

That doesn't actually seem very open-minded.

Kahan and his colleagues conclude that sophisticated reasoning skills have "become tragically entangled in the social dynamics that give rise to pointed, persistent forms of political conflict." When it comes to politically polarized scientific disputes, does this mean that all reasoning tends toward confirmation bias? Maybe not.

In another study, Kahan and his colleagues provisionally suggest that "science curiosity might be an individual difference in cognition that evades this entanglement and promotes genuine receptivity to counter-attitudinal evidence, among persons of opposing political outlooks." The researchers devised a scale using viewing time and engagement with several science documentaries, including Darwin's Dangerous Idea, Your Inner Fish, and Mass Extinction, to judge how curious an individual is about science. The object is to distinguish between an individual's mere comprehension of scientific information from a "general disposition, variable in intensity across persons, that reflects the motivation to seek out and consume scientific information for personal pleasure."

In this study, the researchers sorted their subjects with respect to their political beliefs and their propensity toward scientific curiosity. The researchers report that as science curiosity scores increased, the global warming risk perceptions of both conservatives and liberals also moved up. "Higher levels of science curiosity," the authors note, "were associated with greater acceptance of human-caused climate change among both right-leaning and left-leaning study subjects." This finding stands in marked contrast to many previous studies that have found as numeracy, cognitive reflection, science comprehension, and similar measures of reasoning proficiency increased, so too did political or cultural polarization over contested scientific issues.

Kahan and his colleagues then conducted an experiment in which subjects were exposed to real newspaper headlines that reported skeptical and orthodox scientific findings about climate change in surprising and unsurprising ways. For example, one skeptical unsurprising headline declared "Scientists Find Still More Evidence That Global Warming Actually Slowed in the Last Decade," and one orthodox surprising headline stated "Scientists Report Surprising Evidence: Arctic Ice Melting Even Faster Than Expected."

Subjects then picked the story that most interested them to read. The researchers report that both left- and right-leaning subjects who score "high in science curiosity display a marked preference for surprising information—that is, information contrary to their expectations about the current state of the best available evidence—even when that evidence disappoints rather than gratifies their political predispositions."

The researchers suggest that people who highly curious about science "do not turn this feature of their personality off when they engage political information but rather indulge it in that setting as well, exposing themselves more readily to information that defies their expectations about facts on contested issues. The result is that these citizens, unlike their less curious counterparts, react more open mindedly, and respond more uniformly across the political spectrum to the best available evidence."

To judge from the latest Pew poll numbers, this kind of curiosity—this disposition to seek out scientific information to experience the intrinsic pleasure of awe and surprise—is in short supply in contemporary America.

Show Comments (229)