How Hate Speech Laws Actually Work

An instructive example out of Kenya (and a few from our own backyard)

The most baffling thing about the people—mostly liberals—who push for laws against "hate speech" is their apparent inability to imagine these bans backfiring. In their zeal to punish those who spread sexist, racist, transphobic, or otherwise unfashionable speech, they too often ignore the ways tools of censorship—including hate speech laws—are used to suppress religious, social, sexual, and political minorities around the world.

Consider Kenya. "There is growing evidence that the government is using prosecution for hate speech as a tool to silence its opposition critics," John Onyando writes in the Nairobi Star. "The norm is incendiary speech by pro-government politicians and online activists going unchecked while law enforcement agencies enthusiastically pounce on the mildest expressions by critics."

Kenya's agency tasked with enforcing laws against hate speech is the National Cohesion and Integration Commission (NCIC), formed in 2008 to address ethnic conflicts in the nation. In practice, the agency mostly homes in on those who speak out against the Jubilee Alliance, the political coalition associated with President Uhuru Kenyatta and Deputy President William Ruto. The NCIC has prosecuted Sen. Johnstone Muthama, a leader of the Coalition for Reform and Democracy, which stands in opposition to the Jubilee Alliance; Allan Wadi Okengo, a student activist who criticized Kenyatta on Twitter; student leader Seth Odongo; and blogger Robert Alai, who called Kenyatta an "adolescent president." Okengo, Alai, and Odongo were all sentenced to time in prison.

Moses Kuria, a Parliament member from Gatundu South—home constituency of President Kenyatta and his father, former President Mzee Jomo Kenyatta—was also arrested. But the NCIC invited Kuria to participate in a reconciliation program in lieu of trial, an option the other men were not offered. Only after Kuria continued to post inflammatory material online during the proceedings did the commission rescind its reconciliation offer. And no action was taken when, on national television, Kuria told a group of young people whom he had given knives to "cut up someone if you feel like it."

"One can't avoid the inference that hate speech is an actionable crime only when perpetrated by opposition leaders and activists," Onyando concludes.

Perhaps you think such a selective use of hate speech laws can happen only in countries with especially corrupt or unstable governments. Think again. Because "hate speech" is not narrowly defined, it's up to those in power to decide what qualifies as hate and what doesn't. That often depends on who the speaker is and who has powerful people's sympathies.

In 2012, a British teenager who denounced British military actions in Afghanistan was arrested and charged with "a racially aggravated public order offense."

The First Amendment theoretically pre-empts such laws in the United States. But a lot of Americans favor them nonetheless. A 2014 YouGov poll found that nearly equal numbers of Americans support and oppose laws that would "make it a crime for people to make comments that advocate genocide or hatred against an identifiable group based on such things as their race, gender, religion, ethnic origin, or sexual orientation." Fully 51 percent of Democrat respondents voiced their support.

Meanwhile, colleges and universities—even the public ones that are supposed to follow the First Amendment—have been using the specter of hate speech to justify banning controversial speakers, institute prior review of student newspapers, and implement other forms of censorship and intolerance. At Berkeley, there have been pushes for restrictions on everything from student editorials to fraternity party themes. At Dartmouth, student leaders recently called for a "full inquiry" into a "hate speech" incident involving campus flyers advertising merchandise bearing the school's former sports mascot, the "Dartmouth Indian."

Much of this activism is aimed at things deemed not sufficiently progressive, but some of "the most potent of such campaigns are often devoted to outlawing or otherwise punishing criticisms of Israel," as Glenn Greenwald reported at The Intercept. He pointed to recent action against University of Illinois professor Steve Salaita who had a job offer rescinded due to his "uncivil" denunciations of Israeli conduct in Gaza.

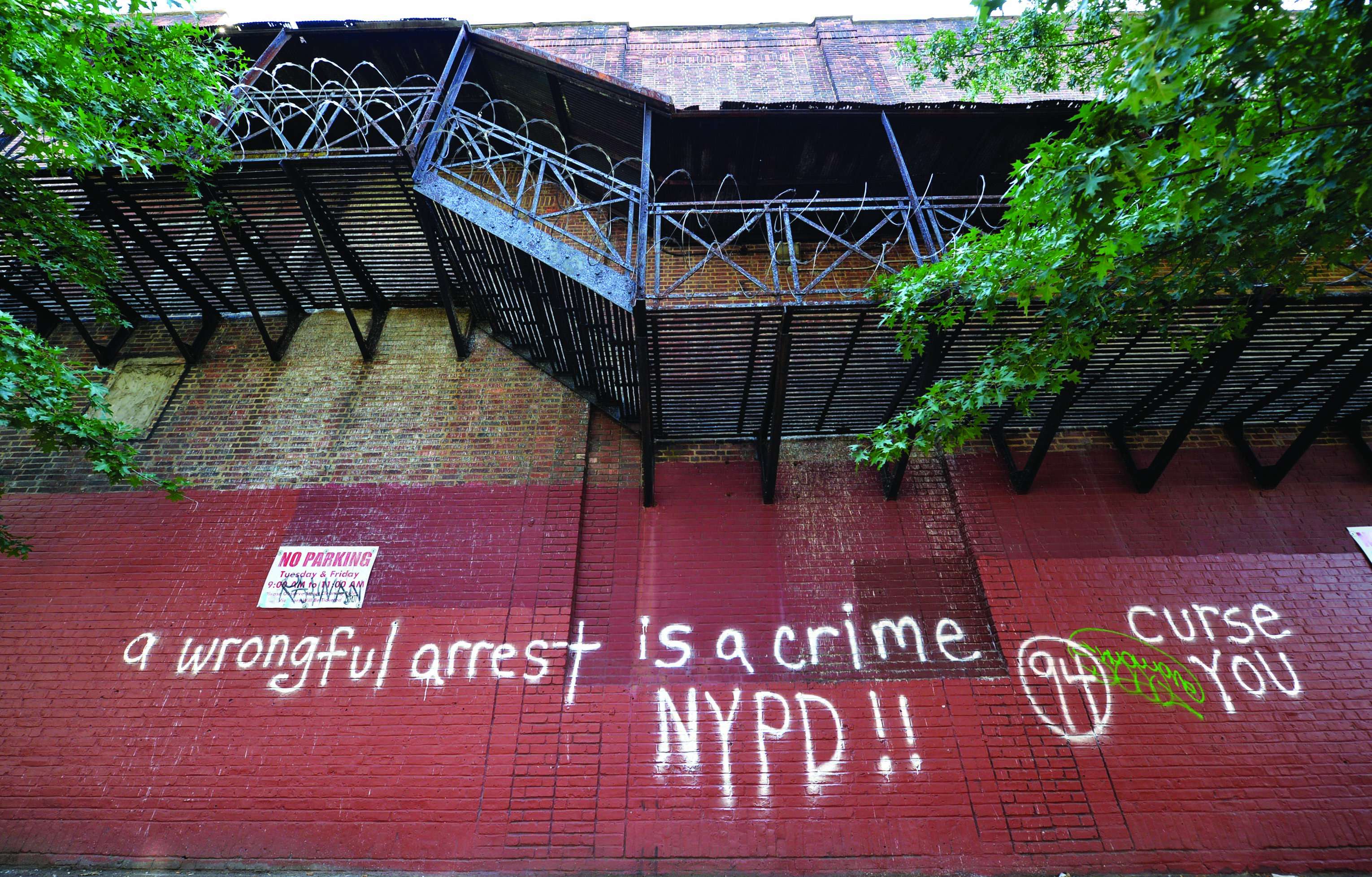

Outside college campuses, there are plenty of ways to punish alleged hate speech that (may) circumvent First Amendment concerns, especially when the speech involves other illegal activity (like spray-painting a building) or could be construed to involve illegal activity (like making hyperbolic "threats" online).

In early 2015, a Brooklyn teen was arrested for a Facebook post featuring emojis of a gun pointed at a cop. One can't imagine prosecutors showing the same zeal if it weren't an authority figure being "threatened."

The Internet is a hotbed of derogatory comments, unserious threats, and all manner of vitriol each and every day, but prosecutors tend to reserve monitoring and investigation for those whose views are unpopular—such as ISIS sympathizers and Holocaust deniers—and those who criticize judges, police, and others in positions of power.

Before liberals rush to endorse laws that would give them even more leeway to punish speech, they should pause to ponder whether they might ever feel the need to criticize authority in "uncivil" terms themselves.

This article originally appeared in print under the headline "How Hate Speech Laws Actually Work."

Show Comments (13)