The Menace of Secret Government

Obama's proposed intelligence reforms fail to safeguard civil liberties

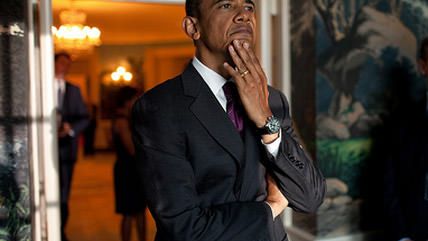

In January, President Barack Obama made a much-anticipated speech at the Department of Justice outlining proposed reforms of the domestic surveillance programs run by the National Security Agency (NSA). The secretive spy agency has taken a public battering ever since former NSA contractor Edward Snowden began blowing the whistle on its clandestine collection of basically every American's telephone records.

"We will reform programs and procedures in place to provide greater transparency to our surveillance activities, and fortify the safeguards that protect the privacy of U.S. persons," the president proclaimed. Unfortunately, Obama's proposed changes to domestic surveillance programs are not nearly transparent enough, and fail to adequately protect the privacy of Americans.

In January, the federal government's Privacy and Civil Liberties Oversight Board, an independent agency charged by Congress with advising the president on the privacy and civil liberties repercussions relating to fighting terrorism, concluded that the NSA's domestic surveillance "implicates constitutional concerns under the First and Fourth Amendments, raises serious threats to privacy and civil liberties as a policy matter, and has shown only limited value." How limited? "We have not identified a single instance involving a threat to the United States in which the telephone records program made a concrete difference in the outcome of a counterterrorism investigation."

The oversight board recommended that the surveillance program be terminated. In his speech, the president said that he had consulted with the board. Yet he did not heed its advice.

Instead of ending the unconstitutional domestic telecommunications spying program, Obama offered what he insisted were "a series of concrete and substantial reforms." These include a new executive order on signals intelligence-that is, data connected with private communications-instructing surveillance agencies that "privacy and civil liberties shall be integral considerations."

The order further admonishes intelligence bureaucrats to make sure their spying actually provides some benefit greater than the embarrassment officials will surely suffer should they be disclosed. This is the "front page test," or how officials would feel if what they are doing were reported on the front page of a newspaper. If discovery equals discomfort, then maybe they shouldn't be doing it in the first place.

And for all its language about being more transparent and solicitous of civil liberties, the new executive order includes a secret classified addendum, the content of which we can only guess at, apprehensively.

Obama's other reform proposals include requiring both the director of national intelligence and the attorney general to review the secret opinions of the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court (FISC) each year, to see which if any can be safely declassified. (Yes, we've gotten to the point where even the legal reasoning of a secret court order is considered secret.)

In addition, the president asked Congress to create a panel of advocates to provide an independent voice in significant cases before the FISC. What might constitute a "significant case" and who would make that decision was left vague.

Using authority created by Section 215 of the PATRIOT Act, the FBI each year issues thousands of national security letters (NSLs) demanding personal customer records from Internet service providers, financial institutions, and credit companies without prior court approval. In addition, the FBI typically imposes indefinite gag orders on anyone who receives an NSL, compounding a Fourth Amendment transgression with an infringement on the First.

While the president proposed nothing to limit the issuance of NSLs, he did promise to amend their use so that the gag orders are no longer indefinite. Unless, that is, "the government demonstrates a real need for further secrecy." Obama further promised to let communications providers give the public more information about the NSLs they receive. In January, for example, Verizon was permitted to announce that the number of NSLs it received last year was somewhere between 1,000 and 2,000. How transparent!

In December, the Review Group on Intelligence and Communications Technologies-a group of five advisers handpicked by the president a few months earlier to review and provide recommendations on how to collect electronic intelligence without violating privacy and civil liberties-recommended that the government not issue NSLs unless it first demonstrates to a court that it has "reasonable grounds to believe that the particular information sought is relevant to an authorized investigation" involving "international terrorism or clandestine intelligence activities." The group also recommended that the gag orders last only 180 days unless reauthorized by a court, and that recipients should be able to challenge the orders. But the president ignored all these recommendations.

The review board strongly recommended that governance of the NSA be reorganized. The group proposed that the agency's director be confirmed by the Senate and that civilians be eligible to hold the position. The panel also suggested that the NSA director should not head up the U.S. Cyber Command, as General Keith Alexander has done during his tenure.

Obama rejected these ideas and nominated another military officer to head both agencies, Vice Admiral Michael Rogers. That's too bad, because the review board's recommendations would be significant improvements.

The review group also argued that "the government should not be permitted to collect and store mass, undigested, non-public personal information about U.S. persons for the purpose of enabling future queries and data-mining for foreign intelligence purposes." Instead, telecom companies or a third-party private consortium should hold such records, which the government could search only pursuant to judicial order.

The president half-adopted those recommendations by ordering the intelligence community and the attorney general to try to figure out a way to transition from the NSA bulk-collection database to "a new approach that can match the capabilities and fill the gaps that the Section 215 program was designed to address."

Three leading civil liberties groups-the Electronic Frontier Foundation, the Center for Democracy and Technology, and the American Civil Liberties Union-issued scorecards on the president's reform speech. All three commended the president for his half-measures to rein in the NSA's bulk telephone spying program, and all three gave the president some points for proposing an independent privacy advocate before the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court.

But all three also excoriated the president for not eschewing future NSA efforts to systematically weaken and sabotage encryption and Internet security technology. The groups also denounced the president for not requiring national security letters to be issued only after judicial approval. Overall, they concluded, Obama flunked. The Electronic Frontier Foundation gave the president a score of 3.42 out of a possible 12, the Center for Democracy and Technology gave him 4 points out of a possible 11, and the ACLU awarded him 4.5 out of 11.

"Permitting the government to routinely collect the calling records of the entire nation fundamentally shifts the balance of power between the state and its citizens," the Privacy and Civil Liberties Oversight Board warned in its report. "While the danger of abuse may seem remote, given historical abuse of personal information by the government during the twentieth century, the risk is more than merely theoretical."

It's a timely if late-breaking reminder of an eternal truth: Secret government is always the chief threat to liberty.

Show Comments (22)