Lessons from Kelo, the Eminent Domain Case That Wiped Out a Neighborhood

Revisiting a notorious Supreme Court ruling.

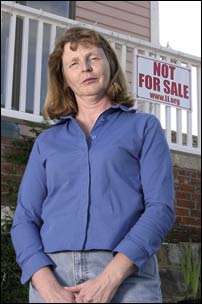

In its 2005 decision in Kelo v. City of New London, the U.S. Supreme Court allowed a Connecticut municipality to forcibly condemn multiple private properties in a well-tended working-class neighborhood in order to clear space for the construction of various upscale amenities, including a luxury hotel, office towers, and apartments. According to the majority opinion of Justice John Paul Stevens, this seizure of private property counted as a legitimate "public purpose" under the Takings Clause of the Fifth Amendment because the city's eminent domain proceedings were part of a "comprehensive" redevelopment scheme that was carefully designed to bring "appreciable benefits to the community."

How did that work out? Writing in the latest issue of The Weekly Standard, Charlotte Allen describes a recent visit to Fort Trumbull, the New London neighborhood that was bulldozed thanks to the Kelo ruling. It is now the city's "most desolate neighborhood," she writes. "Actually, ex-neighborhood, for there was not a residential property standing on the entire tract."

As we've previously reported here at Reason, Kelo was a colossal failure on all counts. Despite prevailing at the Supreme Court, New London's redevelopment plan was scrapped, the razed neighborhood was never rebuilt, and the Pfizer corporation, which inspired the whole saga by inking the original real estate deal that led New London to set its sights on Fort Trumbull, pulled out of the city entirely in 2009. After Hurricane Irene blew through town a couple years later, New London urged city residents to use Susette Kelo's barren former neighborhood as a dump site for storm refuse.

In her piece, Allen makes the case that Kelo is "something more than the story of a particularly nasty and overbearing abuse of either eminent domain or government power in general. It was also a tragedy," she maintains, "with all the classical Greek elements: hubris, turn of fortune, cathartic downfall, and possibly the 'learning through suffering' that Aristotle in his Poetics argued was the point of tragic drama."

That's certainly a plausible interpretation of the case. But there's also at least one major player in this tragedy who has yet to show any signs of learning his lesson: Justice John Paul Stevens.

In his 2011 memoir Five Chiefs, Stevens discussed many of the big cases that he encountered during his long tenure on the bench (he was appointed in 1975 and retired in 2010), including District of Columbia v. Heller (2008) and Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission (2010). But Kelo goes entirely unmentioned in the book, despite the extraordinary public backlash sparked by his controversial majority opinion. I criticized him for this absence at the time, and Stevens later responded to my critique, though his defense left a lot to be desired. In essence, Stevens asserted that Kelo was any easy case since it "adhered to the doctrine of judicial restraint, which allows state legislatures broad latitude in making economic policy decisions in their respective jurisdictions."

Perhaps a future Supreme Court will learn from Stevens' example and avoid another tragedy.

Show Comments (47)