President Biden Should Pardon D.M. Bennett

Issuing a posthumous pardon for Bennett would reaffirm our nation’s commitment to free expression and intellectual freedom.

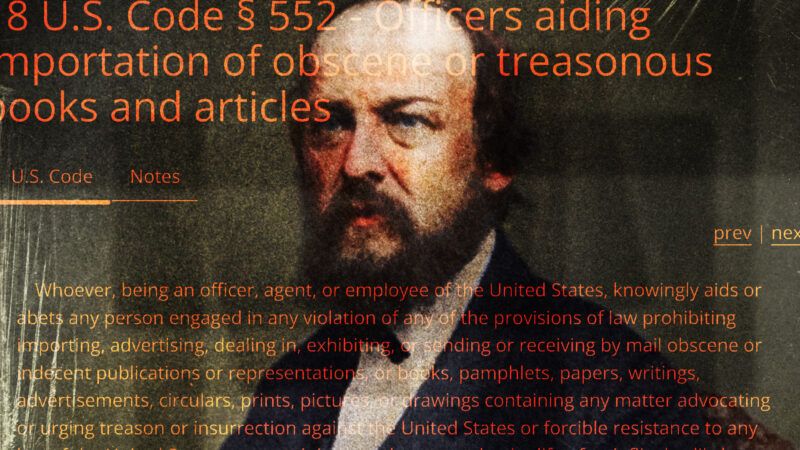

With the stroke of his pen, President Joe Biden could take a stand against authoritarian restrictions on free speech by issuing a posthumous pardon to D.M. Bennett, the freethought publisher convicted of violating the Comstock Act in 1879.

Over the past year, judges have revived the long-dead Comstock Act to justify restrictions on speech and abortion drugs. Supreme Court Justices Samuel Alito and Clarence Thomas even approvingly cited the moribund law in recent arguments.

For these reasons, the Foundation for Individual Rights and Expression (FIRE) has submitted a petition to the president seeking Bennett's pardon both to address the personal injustice resulting from this 145-year-old conviction and also to put the administration on record in opposing the resurgence of this law that threatens the rights of all Americans.

Comstock's Crusade Against Immorality

D.M. Bennett's story highlights the importance of First Amendment protections that have rendered the Comstock Act obsolete. Bennett was the founder and publisher of The Truth Seeker, a freethought journal still in circulation today. He was prosecuted, convicted, and sentenced to a year of hard labor for distributing Cupid's Yokes, a pamphlet attacking the institution of marriage, written by free love advocate Ezra Heywood.

Although the charge was obscenity, Bennett was targeted for opposing the Comstock Act—an 1873 law prohibiting the mailing of any "obscene, lewd, or lascivious" material, anything "designed or intended for the prevention of conception or procuring of an abortion," or anything intended for "any indecent or immoral use." Anthony Comstock, the law's namesake and an anti-smut crusader, lobbied for and personally enforced the law as a special agent of the U.S. Postal Service. Under the law's broad mandate, everything that Comstock considered immoral was by definition obscene and, therefore, illegal.

Comstock's concept of immorality included blasphemy, sensational novels and news stories, art, and even scientific and medical texts. Near the end of his four-decade career as an anti-vice crusader, Comstock claimed he convicted enough people to nearly "fill a passenger train of sixty-one coaches," and also destroyed 160 tons of literature and four million pictures. Most shameful of all, he boasted of causing at least fifteen suicides.

Bennett, whom Comstock described as a "ringleader," became a special target because he actively sought to repeal the Comstock Act and collected signatures for a repeal petition in The Truth Seeker. He also offered to distribute Cupid's Yokes after Comstock prosecuted Heywood. Despite not agreeing with Heywood's free love advocacy, Bennett was outraged that anyone in America could be prosecuted for expressing their views.

Comstock prosecuted Heywood three times for writing and distributing Cupid's Yokes. After an 1878 conviction, President Rutherford B. Hayes pardoned Heywood, writing in his diary that "it is no crime by the laws of the United States to advocate the abolition of marriage" and he did not consider Cupid's Yokes to be obscene. However, Hayes would later deny a pardon to Bennett, who merely distributed the pamphlet, after Comstock personally intervened to block the clemency request. At age 60, Bennett was confined to Albany prison, and the forced labor while there cut short his life.

Abuses like Bennett's conviction spurred a sea change in the law, eventually leading to stronger First Amendment protections. In 1957, the Supreme Court in Roth v. United States declared that "sex and obscenity are not synonymous" and set a high bar for government censorship, nullifying much of the Comstock Act. It has been a dead letter since the mid-twentieth century.

Until now.

The Urgency of Correcting Historical Injustices

Recent decisions threaten to revive the Comstock Act as a vehicle for restricting speech and access to contraceptives and pharmaceutical abortions. Now is the time to recognize and remedy past abuses while reaffirming our commitment to the principles of free expression.

The president is uniquely positioned to do so through the power to pardon. Posthumous presidential pardons are rare but have been granted to correct past injustices and signal future values. It is particularly fitting for President Biden to use the pardon power to highlight the importance of First Amendment rights that have been abridged under an unjust law.

President Thomas Jefferson used executive clemency to undo the damage caused by the Sedition Act of 1798—the law that criminalized expressing any "false, scandalous and malicious writing or writings against the government," and which was used aggressively to punish political opponents of the Adams Administration. And even though the act expired and was never tested in court, the consensus of history is that it was fundamentally at odds with the First Amendment. Jefferson's pardons reinforced this judgment. He would later write that he considered the Sedition Act "a nullity, as absolute and as palpable as if Congress had ordered us to fall down and worship a golden image."

And so it is with the Comstock Act.

The need for a posthumous pardon for Bennett is even more compelling because of the ways the Comstock Act is being used today to threaten individual rights. Bennett was convicted 145 years ago but President Biden should pardon him now; there is never a wrong time to do the right thing.

Show Comments (21)