Tennessee School Board Pulls Maus From Eighth-Grade Curriculum

A grim sign of the bureaucratic mentality controlling public education

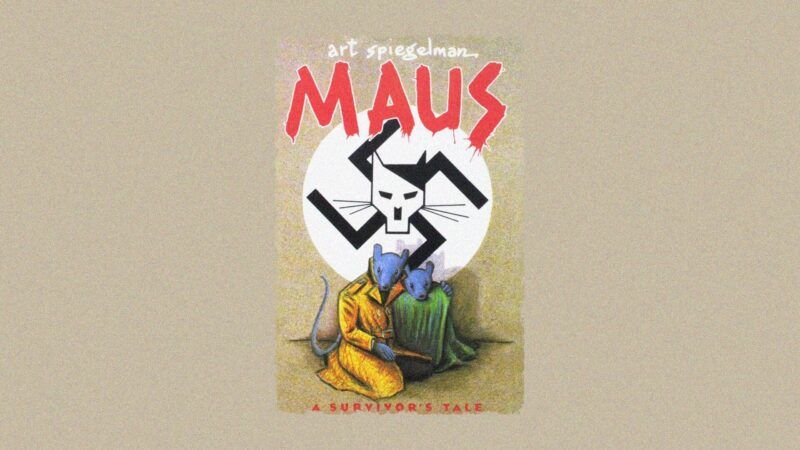

Art Spiegelman's once-controversial and now-canonical graphic memoir Maus has been removed from the McMinn County, Tennessee, school curriculum in a unanimous decision by the local Board of Education.

It was an unexpected irony for the news to hit this week, today being Holocaust Remembrance Day. Spiegelman's Pulitzer-winning book, with its enormous cultural impact and reader-friendliness, has been a, perhaps the, primary pop vehicle of such remembrance over the past few decades. Spiegelman's mother and father were both Auschwitz survivors, and Maus portrays him learning his parents' Holocaust experiences and retelling them—in a riff on classic animal-comics tropes—with Jews as mice and Nazis as cats.

The way McMinn County officials thought through the matter, as revealed by the minutes of their meeting, says a lot about how the public schools deal with serious matters of history and art.

The book was being taught to eighth graders as part of a unit on the Holocaust. A few people attending the meeting objected to the book's "rough, objectionable language," and they initially wanted to redact "eight curse words" and one graphic image. The complaints expanded from there, with board member Tony Allman seeming to believe that the horrors of the Holocaust should not be taught to schoolchildren in general. "Being in the schools, educators and stuff we don't need to enable or somewhat promote this stuff. It shows people hanging, it shows them killing kids, why does the educational system promote this kind of stuff, it is not wise or healthy," he opined in the halls of the McMinn County Center for Educational Excellence.

Allman also brought up obscure details of Spiegelman's career, noting with suspicion that the author who "created the artwork used to do the graphics for Playboy. You can look at his history, and we're letting him do graphics in books for students in elementary school. If I had a child in the eighth grade, this ain't happening. If I had to move him out and homeschool him or put him somewhere else, this is not happening."

Another board member, Steven Brady, explained that Maus is an important part of the eighth-grade curriculum: "Next year in high school, they are going to jump in the deep end on World War II….The thinking here is, here is the best place to give them a little introduction to the Holocaust and things that went on during World War II." Maus, he explained, is the "anchor text," taught with news stories, survivors' stories, and other supplemental materials. He added: "What we have done in anticipation of any of those concerns, we prepared a parent letter to go home to inform them of this topic we are about to study. We went ahead and took the step to censor that explicit content and we went ahead and made sure that all of our books are stamped 'property of MCS' so that if one does come up for some reason, hey look at these words we are teaching in school, no, that's not one of our books."

Board member Jonathan Pierce moved that Maus be removed from the curriculum, arguing that the violent words and actions portrayed would not be allowed on school grounds."The wording in this book is in direct conflict of some of our policies. If I said on the school bus that I was going to kill you, we would be bringing disciplinary action against that child." This bizarre argument shows a complete lack of understanding of the value of historical storytelling.

Lee Parkison, a teacher at the meeting, pointed out that Maus had been approved for use in schools on the state level in Tennessee, notwithstanding the eight words and one picture that raised concerns in McMinn County. The offensive image was not specifically identified in the minutes of the meeting, but it was probably a very vague and easy-to-miss drawing in a story-within-the-story of his human mother's topless dead body in a tub after she killed herself. (Another possible target: male cartoon mice shown nude in a shower in their death camp.) The discussion did not identify the eight forbidden words either, though it alludes to "bitch" and "goddamn." I noticed a "god damn" and a "hell" thumbing through the book this morning, but this book is not rife with harsh language that should shock an early teen.

Board member Mike Cochran felt that mixing Holocaust education with Maus's depiction of Spiegelman's mother's suicide decades after her camp experience, and the harsh language against his survivor father, was not necessary for schoolchildren. Cochran also noted two non-Maus examples from the school curriculum, a poem discussing kisses and ecstasy and a painting of a naked man riding a bull, to support his contention that "the entire curriculum is developed to normalize sexuality, normalize nudity, and normalize vulgar language. If I was trying to indoctrinate somebody's kids, this is how I would do it. You put this stuff just enough on the edges, so the parents don't catch it but the kids, they soak it in. I think we need to relook at the entire curriculum."

Members of the board also seemed to believe that adjusting the work to their preferences might lead to some copyright issues. This non-lawyer is not sure they are correct in assuming that a redacted-to-their-tastes version of Maus would break the law.

While the board insists it is not against teaching the Holocaust, one member admitted that if they can't find a good substitute to anchor the Holocaust module now that Maus has been jettisoned, "It would probably mean we would have to move on to another module."

The U.S. Holocaust Museum told The Washington Post that Maus "has been vital in educating students about the Holocaust through the detailed experiences of victims." Spiegelman himself told CNBC that "I've met so many young people who…have learned things from my book" and that something "very, very haywire" is happening in Tennessee.

Spiegelman's tireless efforts as a cultural ambassador for comics as an art form are a major reason why book-length comic books are considered appropriate for educational curricula to begin with. (Spiegelman's career and impact are discussed at length in my forthcoming book Dirty Pictures, a history of underground comix and its creators.) Schools used to dismiss comics as inconsequential, childish frippery; now, precisely because Maus is so intensely true to his parents' historical experiences, some schools are dismissing it for being all too consequential. This school board not only seriously considered the idea that works depicting violence should be seen as the same as actually threatening violence; it gave the side offering such arguments its unanimous assent. That's a grim sign of the mentality of the bureaucrats controlling public education.

Show Comments (98)