Good News: Biden Says Schools 'Must' Stay Open. Bad News: Many Won't.

The president rightly points out that the federal government has sloshed billions of dollars to make K-12 schools even safer than they already were. Yet many are about to close.

In his big omicron speech and barky mini-press conference Tuesday afternoon, President Joe Biden said some words that will sound almost soothing to the ears of those of us who have been advocating since the summer of 2020 to keep public K-12 schools open, given that "the risk of severe outcomes to kids from coronavirus infection is low, and the risks to kids from being out of school are high," in the words of Harvard health professor Joseph G. Allen in the New York Times.

"We know a lot more today than we did back in March of 2020," Biden pointed out at around the six-minute mark of his speech:

"For example, last year, we thought the only way to keep your children safe was to close our schools. Today we know more, and we have more resources to keep those schools open. You can get 5- to 11-year-olds vaccinated, a tool we didn't have until last month. Today we don't have to shut down schools because of a case of COVID-19. Now, if a student tests positive, other students can take the test, and stay in the classroom if they're non-infected, rather than closing the whole school or having to quarantine. We can keep our K through 12 schools open, and that's exactly what we should be doing."

So far, so promising. The president expanded on the point at around minute 20:

"Look, the science is clear, and overwhelming. We know how to keep our kids safe from COVID-19 in school. K through 12 schools should be open. And that safety is increased if schools require all adults who work in the schools to get vaccinated, and take the safety measures that the CDC [Centers for Disease Control and Prevention] has recommended, including masking. I got Congress to pass billions of dollars in school improvements—ventilation and social distancing. School should be safer than ever from COVID-19. And just Friday, the CDC issued test-to-stay guidelines….COVID-19 is scary, but the science is clear: Children are as safe in school as they are anyplace, assuming the appropriate precautions have been taken. And they've already been funded."

But despite that $197 billion and counting in extra federal COVID funding over the past 21 months, an increasing number of public K-12 schools keep on closing, at least in little spurts. Why? Well, if we're being a bit catty (if truthful), there has been some opportunistic, last-minute, teacher-friendly days off conjured up near weekends and federal holidays:

But the reality is that the rapid omicron surge in positive cases, especially throughout the Northeast and Midwest, is putting strain on school systems that have not figured out a way to translate money into student testing and emergency staffing capacity.

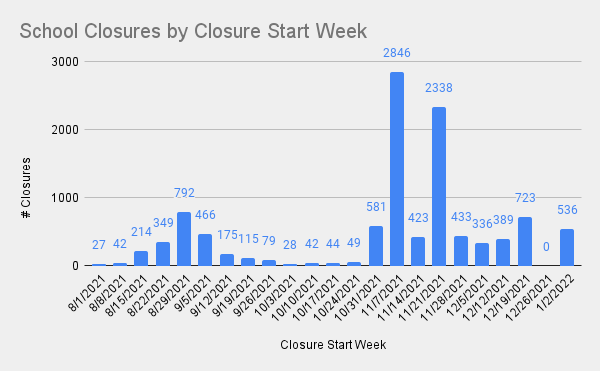

The school-tracking site Burbio provides a thorough weekly survey of school-closing trends; this weekend's report shows "an increase in disruptions beginning the week of December 20th as well as in early January." Details:

"Prince George's County, MD school district, one of the nation's largest with over 200 schools, will be virtual from December 20th through January 14th. 'Educators, administrators and support staff must be able to deliver in-person instruction and other activities in conditions that prioritize their own health, as well as the wellbeing of the school community,' reads the release.

Hamtramck, MI public schools will be virtual for a week post-New Years. 'Out of an abundance of caution, we're implementing a week of virtual learning upon the break's end,' writes the Superintendent.

Dover Middle School, PA shifted to virtual learning December 17th. 'In consultation with a Pennsylvania Department of Health epidemiologist, due to a drastic rise in COVID-19 cases and subsequent quarantining, the Dover Area Middle School will be shifting to virtual learning,' reads the note."

At my eighth-grader's school here in omicron-surging Brooklyn, the last few days before Christmas break have been a confusing mess—a classmate/friend found out late Thursday she'd tested positive; a whole bunch of kids (including ours) stayed home Friday to take tests; those PCR screens during this crazy testing surge took forever to come back (ours arrived…Tuesday afternoon!); students and teachers alike have been straggling in and out, communication with the school has been spotty, and then on Tuesday we received this note:

"We have seen rises in student and staff cases alike, with the greatest impact being on adults. While we want to assure you that classes are being covered by school personnel, we also want to be forthright in saying that we do have an increasing number of staff members who have been affected by this COVID wave."

Positive-testing waves for a virus that has killed more than 800,000 Americans to date is just a flat-out logistical and psychological challenge, and empathy should be afforded to people trying to sort it all out. But since at least fall 2020, there has been a remarkable divergence in the pandemic's impacts on school policies and openness, depending not on comparative viral devastation but on politics.

Democratic-controlled (and teachers union-influenced) states and cities have been the most closed (and most likely to include masking mandates); Republican-controlled polities have been more open and less masked. And private schools everywhere have been more open than their government-run counterparts.

There is every reason to suspect that this pattern will reassert itself during the omicron surge. Blue states have more teacher (and sometimes even student) vaccine mandates, bigger labor shortages, and more scale-thumbing by unions. To say something facially absurd yet annoyingly true, the places that voted for Joe Biden will be the most likely to not deliver on the president's aspiration that "K through 12 schools should be open."

A New Yorker article Monday by Jessica Winter gives a taste of both the power mechanics and frantic atmospherics that has put New York City's public school system on the verge of a daily nervous breakdown, if not quite a systemwide closure:

"Staffing shortages at some schools have compounded the problems faced by overtaxed teachers….[high school English teacher Alex] Driver said that things had been made worse by an agreement that the United Federation of Teachers, the labor union that represents most public-school teachers in New York, struck with the city in its negotiation of the vaccine mandate. The deal gave teachers who refused the vaccine up to a year to change their minds—meaning that principals can't yet make permanent hires to replace them. 'The U.F.T. used our bargaining power for anti-vaxxer teachers instead of for better testing and better safety standards,' Driver said.

A D.O.E. spokesperson told me that 'there are no widespread staffing shortages.' Another D.O.E. spokesperson said via e-mail that the city's supply of teachers and substitutes was comparable to what it was in previous school years. (The D.O.E. did not provide responses to more specific follow-up questions about staff vacancies and substitute numbers.) But multiple teachers and principals told me that these numbers don't square with what they're seeing on the ground. Jake Jacobs is an art teacher at a Bronx middle school that is missing five special-ed teachers, one science teacher, and one language teacher. 'We have not had a single sub all year,' he said. 'The school puts in for subs every day, and nobody ever answers.' A principal at a middle school in Brooklyn, whom I'll call M., was down two teachers for part of the fall. 'I had a spreadsheet of candidates who were vetted and interested in working in our schools, but people did not return our calls,' she said. Like Jacobs, M. reported a total void in substitutes. 'I don't know who or where these subs are, but they're not coming,' she said."

This all jibes with my daughter's reports from eighth grade (indeed, I would not be surprised if "M." was, or had until recently been, her principal). Again, operating schools during a pandemic is a damnably difficult task. But it's one that big-city public school systems in particular have been managing in such a way to repel families.

NPR last week produced a well-researched report about how the 2021–22 public school year—prior to omicron, mind you—failed to produce the enrollment bounce-back many expected after the 2020-21 COVID wipeout year. To the contrary:

"We compiled the latest headcount data directly from more than 600 districts in 23 states and Washington, D.C., including statewide data from Massachusetts, Georgia and Alabama. We found that very few districts, especially larger ones, have returned to pre-pandemic numbers. Most are now posting a second straight year of declines. This is particularly true in some of the nation's largest systems:

New York City's school enrollment dropped by about 38,000 students last school year and another 13,000 this year.

In Los Angeles, the student population declined by 17,000 students last school year, and nearly 9,000 this year.

In the Chicago public schools, enrollment dropped by 14,000 last year, and another 10,000 this year."

And so on.

These big-city enrollment drops overlap significantly with big-city (and blue-state) population drops during the pandemic. The Census Bureau this week reported that Democrat-dominated California, New York, and Illinois led the country in overall population decline between July 1, 2020 and July 1, 2021 (with 367,000, 352,000, and 122,000 people, respectively), while Republican-run Florida, Texas, and Arizona were the biggest gainers (221,000, 170,000, and 93,000). In percentage terms, the loss-leader was D.C., also run by Democrats (-2.9 percent), followed by New York (-1.6 percent) and Illinois (-0.9 percent); the top gainers were, again, Republican-controlled: Idaho (+2.9 percent), Utah (+1.7 percent) and Montana (+1.7 percent).

There are several factors, both short- and long-term, that exacerbate these trends: Taxation levels, housing prices, cost of living, ability to work remotely, and so forth. But I have been hypothesizing since April that many families would physically uproot from heavily closed big-city school districts between the 2020–21 and 2021–22 school years, because "this spring is the first time millions of parents will have truly been able to make a premeditated, non-panicky decision about the best schooling options for their kids."

New York Post columnist Karol Markowicz, a Brooklyn-raised, self-described "New York supremacist" with kids in our school district, announced earlier this month that she was finally abandoning her beloved city for Florida, "because they took away school during the pandemic and not enough of my fellow New Yorkers cared."

As Markowicz elaborated to me and Nancy Rommelmann on December 16, with omicron bearing down on the city, "I can't answer definitely they will definitely not close schools [in New York], right? But in Florida, if you asked me tomorrow—Florida has a massive outbreak, are they closing schools? I can tell you definitively they are not closing schools. That goes a long way." (Markowicz is the subject of an imminently forthcoming Reason Interview with Nick Gillespie podcast interview.)

Allen, in his New York Times op-ed, emphasizes the "remarkably consistent" weekly COVID hospitalization rate for school-age children of one in 100,000 throughout every stage of the pandemic, and pleads with officials everywhere to embrace the mantra that "schools should never close."

"We are coming up on two years of disrupted school," he writes. "For those in the second grade, a life of closed schools, learning behind plexiglass and masks, learning to read without seeing their teachers' mouths and no physical contact on the playground is all they've ever known. This is outrageous, dangerous and fear-based. The Omicron surge may make certain districts want to cling to these measures, but they shouldn't."

Biden deserves credit for his clear statements in favor of keeping schools open. But will his voters listen?

Show Comments (97)