The Volokh Conspiracy

Mostly law professors | Sometimes contrarian | Often libertarian | Always independent

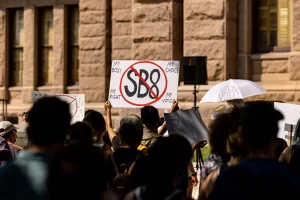

A Murky Decision in the Texas SB 8 Case

The Court rules that the lawsuit against SB 8 can proceed by targeting state licensing officials. But the implications for future cases are far from completely clear.

This morning, the Supreme Court issued its ruling on Texas SB 8, the controversial anti-abortion law structured to evade judicial review. As I have explained in previous posts (e.g. here and here), the key issue at stake in this case is whether Texas can evade judicial review by limiting enforcement authority exclusively to private parties. SB 8 seemingly bars enforcement by state officials, and instead delegates it to private litigants, who each stand to gain $10,000 or more in damages every time they prevail in a lawsuit against anyone who violates the law's provisions barring nearly all abortions that take place more than six weeks into a pregnancy. If Texas' ploy succeeds, it would set a dangerous precedent for insulating attacks on other constitutional rights from judicial review.

Today's Supreme Court decision in Whole Woman's Health v. Jackson, allows preenforcement lawsuits against SB 8 to go forward, but only against state medical licensing board officials, who - eight of nine justices conclude - still have some potential enforcement authority under SB 8. It denies relief against the Attorney General of Texas, state judges, state court clerks, and the one private litigant who was a defendant in the case. The plurality opinion by Justice Neil Gorsuch, joined by three other conservative justices (Barrett, Kavanaugh, and Alito) concludes that relief against the AG is impermissible because of state sovereign immunity, and relief against the clerks is not allowed because the latter's interests are not genuinely "adverse" to those of the abortion providers challenging SB 8:

Private parties who seek to bring S. B. 8 suits in state court may be litigants adverse to the petitioners. But the state-court clerks who docket those disputes and the state-court judges who decide them generally are not. Clerks serve to file cases as they arrive, not to participate as adversaries in those disputes. Judges exist to resolve controversies about a law's meaning or its conformance to the Federal and State Constitutions, not to wage battle as contestants in the parties' litigation. As this Court has explained, "no case or controversy" exists "between a judge who adjudicates claims under a statute and a litigant who attacks the constitutionality of the statute." Pulliam v. Allen, 466 U. S. 522, 538, n. 18 (1984).

On the other hand, Justice Gorsuch concludes that the plaintiffs can bring a preenforcement action against state medical licensing officials. On this issue, eight of nine justices agree with him (all but Justice Thomas):

While this Court's precedents foreclose some of the petitioners' claims for relief, others survive. The petitioners Thomas, Allison Benz, and Cecile Young. On the briefing and argument before us, it appears that these particular defendants fall within the scope of Ex parte Young's historic exception to state sovereign immunity. Each of these individuals is an executive licensing official who may or must take enforcement actions against the petitioners if they violate the terms of Texas's Health and Safety Code, including S. B. 8. See, e.g., Tex. Occ. Code Ann. §164.055(a); Brief for Petitioners 33–34. Accordingly, we hold that sovereign immunity does not bar the petitioners' suit against these named defendants at the motion to dismiss stage.

Gorsuch goes on to reject Justice Thomas' solo dissent arguing that the licensing officials are not proper defendants:

JUSTICE THOMAS suggests that the licensing-official defendants lack authority to enforce S. B. 8 because that statute says it is to be "exclusively" enforced through private civil actions "[n]otwithstanding . . . any other law." See Tex. Health & Safety Code Ann. §171.207(a). But the same provision of S. B. 8 also states that the law "may not be construed to . . . limit the enforceability of any other laws that regulate or prohibit abortion." §171.207(b)(3). This saving clause is significant because, as best we can tell from the briefing before us, the licensing-official defendants are charged with enforcing "other laws that regulate . . . abortion."

Consider, for example, Texas Occupational Code §164.055, titled "Prohibited Acts Regarding Abortion." That provision states that the Texas Medical Board "shall take an appropriate disciplinary action against a physician who violates . . . Chapter 171, Health and Safety Code," a part of Texas statutory law that includes S. B. 8. Accordingly, it appears Texas law imposes on the licensing-official defendants a duty to enforce a law that "regulate[s] or prohibit[s] abortion," a duty expressly preserved by S. B. 8's saving clause…..

JUSTICE THOMAS advances an alternative argument. He stresses that to maintain a

suit consistent with this Court's…. precedents, "it is not enough that petitioners 'feel inhibited' " or " 'chill[ed]' " by the abstract possibility of an enforcement action against them…. Rather, they must show at least a credible threat of such an action

against them…. [W]e agree with these observations in principle and disagree only on their application to the facts of this case. The petitioners have plausibly alleged that S. B. 8 has already had a direct effect on their day-to-day operations….. And they have identified provisions of state law that appear to impose a duty on the licensing-official defendants to bring disciplinary actions against them if they violate S. B. 8. In our judgment, this is enough at the motion to dismiss stage to suggest the petitioners will be the target of an enforcement action and thus allow this suit to proceed.

If the plaintiffs prevail in their lawsuit against the licensing officials, they will, most likely, be able to get an injunction that applies only against those defendants. But the precedent set can then be used to defend against lawsuits by private SB 8 litigants, and thus should eliminate all or most of the "chilling effect" created by SB 8.

This should enable the plaintiffs to get relief against SB 8, should federal courts ultimately rule it unconstitutional on substantive grounds. As Justice Gorsuch notes, there is also preenforcement state-court litigation against SB 8, which just yesterday resulted in a decision ruling against its enforcement mechanism. One way or another, the SB 8 ploy is likely to fail to insulate SB 8 itself against preenforcement review. The big question, however, is whether Texas and other states can successfully insulate other similar laws from judicial review.

Justice Sotomayor's partial dissent on behalf of the three liberal justices raises the possibility that states can do just that, simply by going farther than SB 8 did in precluding enforcement by government officials:

My disagreement with the Court runs far deeper than a quibble over how many defendants these petitioners may sue. The dispute is over whether States may nullify federal constitutional rights by employing schemes like the one at hand. The Court indicates that they can, so long as they write their laws to more thoroughly disclaim all enforcement by state officials, including licensing officials. This choice to shrink from Texas' challenge to federal supremacy will have far-reaching repercussions. I doubt the Court, let alone the country, is prepared for them…..

[B]y foreclosing suit against state-court officials and the state attorney general, the Court clears the way for States to reprise and perfect Texas' scheme in the future to target the exercise of any right recognized by this Court with which they disagree.

This is no hypothetical. New permutations of S. B. 8 are coming. In the months since this Court failed to enjoin the law, legislators in several States have discussed or introduced legislation that replicates its scheme to target locally disfavored rights. What are federal courts to do if, for example, a State effectively prohibits worship by a disfavored religious minority through crushing "private" litigation burdens amplified by skewed court procedures, but does a better job than Texas of disclaiming all enforcement by state officials? Perhaps nothing at all, says this Court. Although some path to relief not recognized today may yet exist, the Court has now foreclosed the most straightforward route under its precedents. I fear the Court, and the country, will come to regret that choice.

This is a genuine danger. It is the main reason for my own support for the SB 8 plaintiffs, as well as that of many others concerned about the threat to other constitutional rights. On the other hand, given the reach of the modern regulatory state, litigants will often - perhaps almost always - be able to find some state or local regulatory official of some kind, who has some kind of tangential connection to enforcement of the law in question. For example, the "religious minority" posited by Justice Sotomayor may be subject to regulation by state officials tasked with enforcing laws involving nonprofit organizations (if the minority's church or other house of worship has nonprofit status), officials regulating land use (if they use property to conduct their services), and so on.

If the tenuous connection between the medical licensing boards and SB 8 is enough to allow the present case to go forward, other indirect connections may be enough, as well. It is, notable, also, that Justice Gorsuch highlights the fact that "[t]he petitioners have plausibly alleged that S. B. 8 has already had a direct effect on their day-to-day operations" as one of the reasons why their case against the licensing officials can go forward. The "direct effect," is, of course, brought on by plausible fear of ruinous litigation. If that is a relevant factor in this case, it might be in others, too.

In sum, it may be difficult for states to insulate SB 8-like laws from judicial review, because it may not be possible to foreclose all the ways in which various kinds of state and local officials might have some kind of indirect enforcement authority. All sorts of private organizations and individuals are subject to various kinds of licensing rules, land-use regulations, tax exemptions, and so on. And all of these might have at least a tangential connection to an SB 8-style law.

But the ultimate impact on future SB 8-like laws remains uncertain. We can expect a constant cat-and-mouse game to arise, as state governments try to insulate these types of schemes from judicial review, while private parties targeted by them search for state and local officials to sue, based on some kind of connection to the law. Federal courts will then have to try to sort through the confusion on a case-by-case basis.

The difficulty of resolving future cases is heightened by the fact that there is no one opinion that commands a majority of the Court on the crucial question of which government officials can be sued and why. Justice Gorsuch's opinion has the support of only four justices. Justice Thomas' opinion that would have barred all the anti-SB 8 lawsuits commands only his own vote. Chief Justice Roberts' opinion that would have allowed lawsuits against the Texas attorney general and state-court clerks commands four votes, as well. And Justice Sotomayor's opinion, which would go further than Roberts in some ways, only has the support of the Court's three liberals.

The part of Justice Gorsuch's opinion focusing on the Attorney General, state clerks, and the one private defendant is styled as an "opinion of the Court," and does have the support of a majority. But the most important part going forward is the section on the licensing board officials, which is described only as an opinion by Gorsuch.

Probably, Gorsuch's opinion is the one lower courts will view as binding, under United States v. Marks (1977), which requires them to credit the Supreme Court opinion resolving the case on the "narrowest grounds." But the issue is not a certain one. Moreover, it is not clear how tight a connection between the state regulators and enforcement of the law in question is needed in order to authorize a lawsuit against the former.

All of these problems could have been avoided if only the Court had adopted the sensible position urged by Chief Justice Roberts in his partial concurring opinion:

In my view, several other respondents are also proper defendants. First, under Texas law, the Attorney General maintains authority coextensive with the Texas Medical Board to address violations of S. B. 8. The Attorney General may "institute an action for a civil penalty" if a physician violates a rule or order of the Board. Tex. Occ. Code Ann. §165.101….

The same goes for Penny Clarkston, a court clerk. Court clerks, of course, do not "usually" enforce a State's laws. Ante, at 5. But by design, the mere threat of even unsuccessful suits brought under S. B. 8 chills constitutionally protected conduct, given the peculiar rules that the State has imposed. Under these circumstances, the court clerks who issue citations and docket S. B. 8 cases are unavoidably enlisted in the scheme to enforce S. B. 8's unconstitutional provisions, and thus are sufficiently "connect[ed]" to such enforcement to be proper defendants. Young, 209 U. S., at 157. The role that clerks play with respect to S. B. 8 is distinct from that of the judges. Judges are in no sense adverse to the parties subject to the burdens of S. B. 8. But as a practical matter clerks are—to the extent they "set[ ] in motion the machinery" that imposes these burdens on those sued under S. B. 8. Sniadach v. Family Finance Corp. of Bay View, 395 U. S. 337, 338 (1969).

Justice Gorsuch does highlight other ways in which judicial review remains available in this case, including through preenforcement actions in state court of the kind already underway against SB 8. But actions in state court could potentially be precluded by state law. Moreover, one of the main functions of federal courts is to provide a forum for constitutional claims against state and local governments that is independent of the latter's own authority.

In sum, the ultimate implications of the SB case remain to be seen, and will surely be litigated in future cases. Perhaps the only people who can be truly satisfied with today's result are all the lawyers who will get extra business, as a result of it.

UPDATE: I have made some additions to this post.

Show Comments (50)