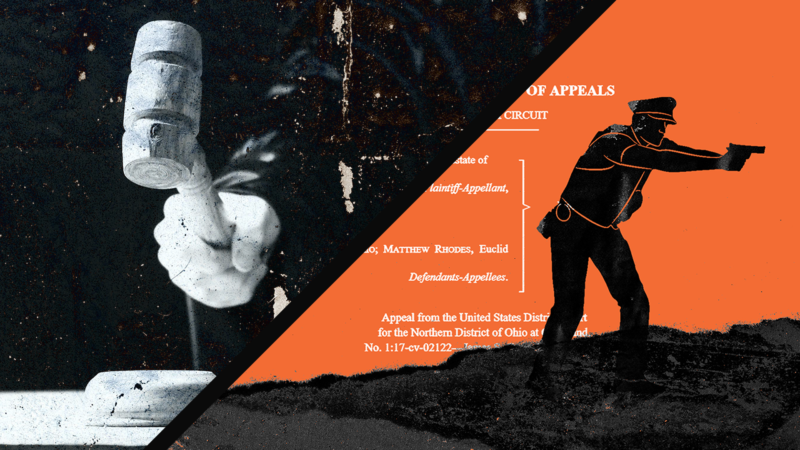

A City Got Protections From Qualified Immunity After a Cop Killed a Man. SCOTUS Won't Hear the Case.

The decision will make it even more difficult for victims to hold the government accountable when their rights are violated.

Since May of 2020, discussions of police reform have been a mainstay among different corners of American society: the chattering classes, the politicians, the protesters, the public at large. Central to that conversation has been qualified immunity, the legal doctrine that prohibits victims of government abuse from suing state actors unless the exact way their rights were infringed on has been addressed in a prior court ruling. Over the last year, Congress has moved from refusing to rectify the issue to considering reining it in significantly.

Yet those efforts took a blow Monday when the Supreme Court declined to intervene in a major case that promises to further obstruct people from holding the government accountable when their rights are violated.

In 2017, Euclid Police Department (EPD) Officer Matthew Rhodes shot and killed Luke Stewart, 23, shortly after waking him up in his car around 7 a.m. in Euclid, Ohio. Along with Officer Louis Catalani, Rhodes had attempted to forcefully eject Stewart from his vehicle. Neither officer announced they were law enforcement, nor was Stewart ever informed he was under arrest, as he had not committed any known crime.

After a brief struggle that lasted just over a minute, Rhodes shot Stewart five times.

A jury in civil court could deduce that Rhodes infringed on Stewart's constitutional rights, said the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 6th Circuit last August. One would assume so. But the court then turned around and awarded the officer qualified immunity, barring Stewart's estate from suing.

This story isn't really about Rhodes, however. It's about Euclid, and the 6th Circuit's decision to extend qualified immunity protections to the city—a ruling that directly contradicts Supreme Court precedent.

"The Supreme Court is simply buying itself some time," says Anya Bidwell, an attorney at the Institute for Justice. "There is little doubt that the 6th Circuit is misreading the high court's precedent by extending qualified immunity protections to municipalities. And we are already seeing this unfortunate trend percolating through other circuit courts. It is just a matter of time before the Supreme Court will have to confront the issue."

In this case, Euclid received those protections even though the 6th Circuit admitted the city's police training materials were "tasteless" and "inappropriate," as well as "perhaps inadequate" for properly preparing officers for the field. Some examples: The city weaved in Chris Rock's comedy routine on racist cops who beat up black people—"Get a white friend!" he says—and included an image of a cop beating a suspect in the prone position with a satirical caption on use of force.

The Stewart estate was prohibited from approaching a jury in civil court over those "inadequate" materials, though, because it was not "clearly established" in prior case law that Rhodes' actions—when he shot Stewart multiple times after waking him up in the early morning hours—were unconstitutional.

Such is the whimsical standard so often applied by the courts when they are considering qualified immunity defenses. The doctrine has protected four cops who assaulted a man after pulling him over for broken lights, two cops who allegedly stole $225,000 while executing a search warrant, a cop who shot a 15-year-old who was about to go to school, two cops who beat up and arrested a man for the crime of standing outside of his own house, and a cop who shot a 10-year-old child while aiming at a nonthreatening dog.

In other words, Rhodes skirting accountability is business as usual. But applying that same logic to the city cuts against the Supreme Court's own guidance on the matter and will only further expand the difficulties victims face in trying to hold the government to account for misconduct. It's yet another avenue blocked off.

That decision—and the high court's demurral in considering it—could have major implications for how Congress addresses qualified immunity. Sen. Tim Scott (R–S.C.) has been one of the few congressional Republicans willing to come to the table on the issue, proposing a compromise last month to hold cities liable for nefarious actions committed by officers in their individual capacities. Yet if the federal courts now consider those same cities eligible for qualified immunity by association, then that plan may be a dud.

Show Comments (40)