The Real Problem With Alan Dershowitz's Position on Quid Pro Quos and Impeachment

Trump's lawyer did not say a president "can do anything" to get re-elected, but he did say that goal cannot count as a corrupt motive.

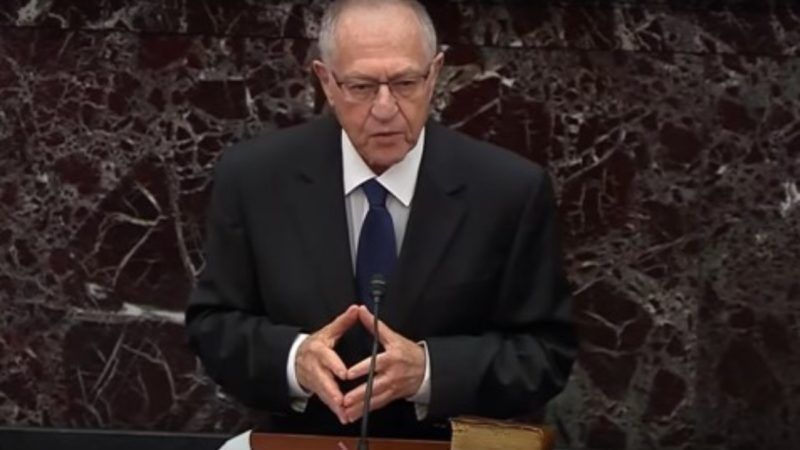

Harvard law professor Alan Dershowitz, one of the attorneys representing Donald Trump in his Senate trial, complains that his critics are misrepresenting his position on quid pro quos and impeachment. "They have mischaracterized my argument as if I claimed that a president who believes his reelection is in the national interest can do anything," Dershowitz writes in The Hill. "I said nothing like that."

It is true that Dershowitz never said a president "can do anything" to get re-elected. He made it clear, for example, that a president who commits crimes to get re-elected—Richard Nixon, say—could be impeached. But Dershowitz's comments during Wednesday's question-and-answer session went further than he admits by implying that the desire to stay in office cannot count as a corrupt motive that renders otherwise legal conduct an impeachable abuse of power.

Here is the question to which Dershowitz was responding: "As a matter of law, does it matter if there was a quid pro quo? Is it true that quid pro quos are often used in foreign policy?"

Dershowitz rightly responded that a quid pro quo involving a foreign government is not necessarily improper. If a president conditioned aid to Israel on a halt to settlement activity or conditioned aid to the Palestinian Authority on an end to payments for the families of terrorists, he said, "there is no one in this chamber who would regard that as in any way unlawful. The only thing that would make a quid pro quo unlawful is if the quo were in some way illegal."

That last part is tautological, of course, and it elides the question of whether a president's conduct can be impeachable even if it is not illegal. But Dershowitz conceded that the motive for a quid pro quo matters. "There are three possible motives that a political figure can have," he said. "One, a motive in the public interest, and the Israel argument would be in the public interest; the second is in his own political interest; and the third, which hasn't been mentioned, would be in his own financial interest, his own pure financial interest, just putting money in the bank."

As an example of a quid pro quo motivated by personal financial interests, Dershowitz described "an easy case" in which "a hypothetical president" tells a foreign government, "Unless you build a hotel with my name on it and unless you give me a million-dollar kickback, I will withhold the funds." The motive in that situation, he said, "is purely corrupt and in the purely private interest." Such a quid pro quo also would clearly violate the federal bribery statute that makes it a crime for a U.S. government official to solicit "anything of value…in return for…being influenced in the performance of any official act."

By contrast, Dershowitz said, when a president offers a quid pro quo "in his own political interest," that is "a complex middle case," because the president might reason this way: "I want to be elected. I think I am a great president. I think I am the greatest president there ever was, and if I am not elected, the national interest will suffer greatly."

In his trial comments, his piece in The Hill, and his self-defense on Twitter, Dershowitz emphasized cases involving "mixed motives": The president does something he believes is in the national interest while recognizing that it will also benefit him politically. Dershowitz warned that it would be dangerous for Congress to constantly parse the president's motives in such situations with an eye toward impeaching him, since so many decisions fall into that category. "Everybody has mixed motives," he told the senators, "and for there to be a constitutional impeachment based on mixed motives would permit almost any President to be impeached."

But the articles of impeachment do not allege that Trump had mixed motives when he pressured the Ukrainian government to announce an investigation of former Vice President Joe Biden. While Trump claims he was concerned about rooting out official corruption in Ukraine, the Democrats say, that is merely a post hoc cover for his true motive: discrediting the candidate he viewed as the biggest threat to his re-election. Dershowitz's argument that a president might sincerely and legitimately equate his re-election with the national interest suggests that the Ukraine quid pro quo was perfectly proper even if Trump's sole aim was tarring a political rival.

"Every public official whom I know believes that his election is in the public interest," Dershowitz said. "Mostly, you are right. Your election is in the public interest. If a president does something which he believes will help him get elected—in the public interest—that cannot be the kind of quid pro quo that results in impeachment."

Dershowitz implied that a quid pro quo can be impeachable only if it is "unlawful." According to the Government Accountability Office, Trump's freeze on military aid to Ukraine was unlawful, since it violated the Impoundment Control Act. And as George Mason law professor Ilya Somin has noted, Trump's quid pro quo arguably violated a federal extortion statute. That law applies to someone who "knowingly causes or attempts to cause any person to make a contribution of a thing of value (including services) for the benefit of any candidate or any political party, by means of the denial or deprivation, or the threat of the denial or deprivation, of…any payment or benefit of a program of the United States" if that payment or benefit "is provided for or made possible in whole or in part by an Act of Congress."

While the articles of impeachment do not allege violations of these or any other laws, Dershowitz concedes that "criminal-like behavior akin to treason or bribery" is impeachable even if it's not "a technical crime with all the elements." Defending his position on Twitter yesterday, he again implied that impeachment does not require "unlawful" conduct. "A president seeking re-election cannot do anything he wants," he said. "He is not above the law. He cannot commit crimes. He cannot commit impeachable conduct." The category of "impeachable conduct," in other words, is broader than the category of "crimes."

That means some abuses of presidential power, such as a pre-emptive self-pardon or politically motivated criminal investigations, can be grounds for impeachment even if they are technically legal. Motives matter. But if a politician's desire to keep his job counts as a legitimate motive because he believes his re-election is "in the public interest," noncriminal abuses of power aimed at avoiding electoral defeat can never be impeachable. That seems to be Dershowitz's position, and it means that Congress has no authority to remove a president who abuses his powers so he can continue to exercise those powers.

Show Comments (137)